Participants

Route

Description

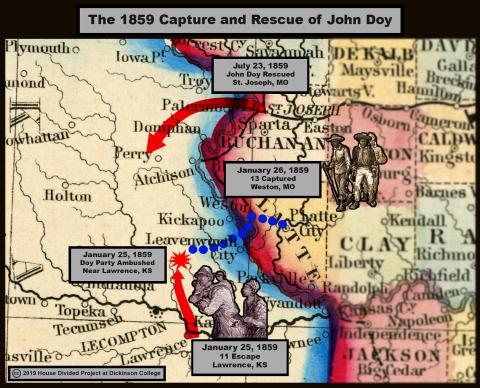

On January 25, 1859, abolitionist John Doy, two free African Americans Wilson Hays and Charles Smith, attempted to lead 11 freedom seekers from various locations across western Missouri to freedom in Iowa. They were recaptured near Lawrence, Kansas. Doy was later rescued from prison to great fanfare, while Smith and one of the freedom seekers, Bill Riley, also managed to escape Missouri authorities. The others, however, were not so fortunate, and apparently sold down to the Deep South.

Full Narrative

To view this full narrative with all of its embedded multi-media, please go to the 1859 Kansas Stampede post at our research blog. For a printable version, download this PDF.

DATELINE: LAWRENCE, JANUARY 25, 1859

In the early morning hours of January 25, 1859, three white abolitionists, two free blacks and a group of 11 Missouri freedom seekers left Lawrence, Kansas on a dangerous mission. Led by self-anointed “Doctor” John Doy, an Englishman who had recently settled in the Kansas Territory, the African Americans were attempting to reach at least Iowa, where they would be safer from the roving bands of slave catchers and kidnappers that were then terrorizing the territory’s black residents. Traveling in two covered wagons—one driven by Doy’s 25-year-old son Charles, and the other by 23-year-old Wilbur F. Clough, the son of a local pastor—the group crossed the Kansas River and headed north towards Oskaloosa, Kansas. Leaving nothing to chance, the three women and two children in the group were concealed within the wagons, while Dr. Doy rode on horseback and the eight men walked behind, on lookout for any potential threats. About 12 miles north of Lawrence, Doy believed “the road was clear,” and directed the men to climb into the wagons “as we had quite a long descent before us, and would go down it at a brisk pace.” [1]

But then suddenly a posse of “ten to fifteen men, fully armed and mounted” rushed out from a nearby ravine, ordering the group to halt. Within the covered wagons, the freedom seekers could neither fully see the events unfolding outside, or defend themselves from the approaching slave catchers. When Doy demanded that the armed men produce their “process,” or paperwork attesting that those within the wagons were escaped slaves, a Kansas resident named Hiram C. Whitley gruffly pressed his revolver to the Englishman’s head, and bellowed, “Here it is.” In a matter of hours, the freedom seekers’ trek towards safer soil had been transformed into a horrific ordeal. [2]

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

While subsequent newspaper accounts did not explicitly label Doy’s group escape from Kansas as a “stampede,” presumably because the actual escapes from Missouri enslavement had occurred in pairs and smaller groups in serial fashion. Yet, in the days and weeks following the larger group’s capture in Kansas, at least two Missouri papers complained about the growing frequency of slave stampedes along the border. The editors of the St. Louis Central Christian Advocate likely had the recent Doy episode in mind when acknowledging on February 2 that “stampedes of slaves are of frequent occurrence.” [3] Likewise, the St. Louis News complained that “slaveholders on the border are beginning to suffer severely from the constantly occurring stampede of slaves.” While not directly mentioning Doy, the paper’s description of a “stampede” closely mirrored the details of the the recent case. Missouri slaves, the paper contended, “are enticed in gangs of dozens and scores, by sympathizers, into Kansas, kept concealed in that territory for a time, and then sent toward Canada, through Iowa.” [4]

The capture of Doy’s group also came at a moment of especially heightened tensions along the Kansas-Missouri border. Just a month earlier, on December 20, 1858, the notorious abolitionist John Brown, had led an armed band on a raid into Vernon County, Missouri, that eventually freed 11 enslaved people (twelve, if you count a baby born en route). Yet when the party reached Kansas soil, their progress had initially been slowed by the chilly prairie winter, and they remained near Lawrence, Kansas well into January. [5]

Although a number of free African Americans and freedom seekers had settled near Lawrence by 1859, the frequent forays of kidnappers into Kansas made their status increasingly tenuous. Even as white anti-slavery settlers denounced these “high-handed crimes” and called for more “energetic legislation” to protect their African American neighbors, Lawrence’s black residents increasingly were taking matters into their own hands. [6]

Two of these black men from the troubled territory, Wilson Hays, originally from Cincinnati, Ohio, and Charles Smith, from Brownsville, Pennsylvania, worked as cooks at the Eldridge House, a hotel in Lawrence. They probably joined Doy as fellow armed agents helping him with the relocation of the recently enslaved Missourians, or perhaps as part of a general contingent of free blacks seeking refuge in Iowa (as Doy himself later claimed disingenuously in his 1860 memoir). As Hays and Smith left no accounts offering their own perspectives, the truth remains uncertain. [7]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Regardless, the main body of the group consisted of 11 escaped slaves, including 10 from western Missouri and one from Leavenworth, Kansas on the border. At least six of the freedom seekers were from Kansas City and the surrounding area: Dan Bright, Ben Logan, Bill Riley, Abe Robey, Catherine West, and an unidentified child. Another enslaved woman, Melinda Wilson, hailed from nearby Clay County, Missouri, while the wife of Bill Riley (whose name was not recorded) came from farther east in Lexington, Missouri. Elsewhere, a man named Dick Newman had fled bondage from nearby Weston, Missouri, while Ranson Winston had escaped from St. Clair County, some distance to the south. The group was rounded out by Mary Russell, an enslaved woman who had escaped from Leavenworth, Kansas. The English-born Doy had spent several years in Rochester, New York, before relocating to Kansas. Regarded as a man of “considerable intelligence,” Doy was also a watercure (hydropathy) practitioner, and after settling in Kansas during the mid-1850s, he began signing his name “John Doy M.D.” [8]

In agreeing to help conduct the group to safety, Doy was also relying upon a verbal agreement with John Brown that the two groups of freedom seekers would set off together, sharing an “escort” of about ten armed men. However, the plan quickly went awry. Despite Doy’s “earnest remonstrances,” Brown demurred on his original promise, insisting that he needed “the whole of the escort” to protect his own group, especially after Missouri’s infuriated governor placed a $3,000 reward on his head. According to Doy, a remorseful Brown later expressed his regret over the decision, which left Doy’s group completely unprotected. [9]

Quickly overwhelmed on January 25th, Doy’s group had little choice but to surrender when the band of slave catchers suddenly encircled their two wagons on the road north of Lawrence. With pistols drawn, the slave catchers tied up the freedom seekers “one by one,” before turning the wagons around and beating a hasty retreat for Missouri soil. Passing near Easton and Leavenworth, the Doy entourage was taken at gunpoint to the Rialto Ferry, and then across the Missouri River to Weston, Missouri. Once on the Missouri shore, they were pilloried and jeered by a raucous pro-slavery mob. Doy, forced to ride through the crowd on horseback, recalled that “my coat was nearly torn from my back; the skirts and sleeves were rent in pieces, and divided among the mob as relics of a ‘live abolitionist.’” While Doy listened to the deafening chants of “Hang him!” echoing through the air, the 13 black men, women and children were placed in a wagon and driven to a building in Weston, where they were held for the night. [10]

Although Clough, one of the white abolitionists who had driven the second wagon, was soon released, after two nights in Weston, Doy and his son were removed to a jail in nearby Platte City. In a letter penned to a Lawrence newspaper, Doy vividly described the conditions of the windowless, “iron box, or metallic coffin, in which we eat, sleep, and are shown to persons, who, with a candle, take a view of the ‘two live Abolitionists.’” [11]

Yet while Doy suffered in a Missouri prison, the African Americans captured with him faced a more frightful fate. Elated at the capture of Doy’s group, the Weston Argus had published an extra edition on January 26 to chronicle “the most gallant achievement and effective vindication of our rights ever since the war upon slave property has been inaugurated.” Denying agency to the 13 freedom seekers, the Argus asserted that they had been “stolen” by “three white conductors,” who were now in custody. The paper published the names and descriptions of 10 African Americans, identifying the alleged slaveholders of 8 of the captives. [12]

From the two free African Americans seized with the group—Wilson Hays and Charles Smith—Doy learned that the other freedom seekers “had been taken away forcibly or prevailed on to choose masters.” Most, it appears, were sold to the Deep South within days of the group’s capture. The “thirteen negroes recently captured,” reported a St. Louis paper, were placed on board a steamboat “bound for the New Orleans market, a point that has no connection with the Underground Railroad—as yet.” And even though Hays and Smith continued to insist that they were free, on February 3 the slave catcher Jake Hurd entered the Platte City jail and “whipped them most unmercifully to make them confess that they were slaves.” Unable to extract a confession, Hurd and another man, George Robbins, nonetheless handcuffed the two men and took them to Independence, Missouri. While Smith managed to escape and apparently returned home to Pennsylvania, Hays was reportedly sold for $1,000. [13]

Another freedom seeker, 35-year-old Bill Riley, also made a successful break for freedom. Imprisoned in the Platte County jail along with Doy, Riley took hold of a fireplace poker from a nearby stove and succeeded in “burning out an iron bar from the logs in which it was fastened across the window.” Doy and his son were “shut up in an iron cage within the general enclosure,” and could not join Riley in his escape. After walking 10 miles, Riley reached the Missouri River, where he utilized the “floating cakes of ice” left by the frigid February weather to reach a small island the middle of the river, hiding “in the young cottonwoods” for two days and nights. After another dash over the “running ice” to the Kansas shore, Riley trod the remaining “35 or 40 miles” to Lawrence, where he arrived on February 23, making contact with local abolitionists who helped to conceal him. [14]

In the meantime, Doy was bracing for the legal consequences. His lawyers managed to move the site of the impending trial to St. Joseph, Missouri, where they hoped to draw a more impartial jury. The initial trial in late March resulted in a hung jury or mistrial, and Missouri prosecutors subsequently released Charles Doy. However, authorities continued with their efforts to convict the elder Doy, and succeeded at a second trial held in June 1859. Doy was then convicted of “seducing” one of the freedom seekers, Dick Newman, and sentenced to five years of hard labor. Prosecutors claimed that Doy had actually crossed the border into Missouri and “abducted” Dick. Doy’s defense countered that Dick had a pass from his slaveholder permitting him to attend a dance in Kansas. Dick, who when captured “had nothing with him but a bundle of clothing and his wife’s miniature with a lock of her hair,” was not allowed to testify under Missouri law. [15]

While Doy filed an appeal, a contingent of Lawrence abolitionists decided to take matters into their own hands. On July 23, as Doy awaited transportation to the state penitentiary in Jefferson, a Kansas man named Silas S. Soule visited the beleaguered abolitionist, slipping him a note that simply read, “Be ready at midnight.” Soule was part of a group of 10 Kansas abolitionists (including Charles Doy), who by that evening had stealthily moved into St. Joseph. As promised, around midnight two men arrived at the jail, under the guise of locking up a horse thief, who appeared to be shackled at the wrists. Yet when the jailer allowed them to enter, the purported horse thief suddenly “freed his wrists from his bonds,” while another man aimed a revolver at the jailer’s chest. “We’ve come to take Dr. Doy home to Kansas, and we mean to do it,” one of the abolitionists bellowed out. “So you’d best be quiet.” Two days later, on July 25, the group arrived back in Lawrence to a triumphant reception. [16]

Although Doy’s safe return was a source of celebration amongst Lawrence’s tightly knit abolitionist community, many were convinced that Doy had been “betrayed by a professed friend,” resulting in the group’s capture back in January. [17] “There were only ten men who knew when these people were to start,” noted Mary Brown, the daughter of a Lawrence pastor, “one of those ten must have told the Missourians all about their plans.” [18] Hiram Whitely, the Kansas man who had aimed a revolver at Doy, was suspected of having masterminded the betrayal. After skipping town, Whitley made the mistake of returning to Lawrence in August 1859, where he was spotted on the street by Doy and forced to give his own confession at gunpoint. In a surprising turn, Whitley then implicated a New Hampshire emigrant named J.J. Hussey, a former Free State advocate who had fallen on hard times and collaborated with the Missourians in exchange for a reward. It was Hussey who had apparently enlisted the help of Whitley and James Garvin, Lawrence’s Democratic postmaster, and tipped off the slave catchers as to the route of Doy’s party. [19]

Throughout the polarized nation, the reaction to Doy’s dramatic rescue was mixed. With sectional attitudes over slavery hardening, many Northern newspapers greeted Doy’s deliverance with ecstatic headlines. “Never was a man more unfairly convicted and unjustly sentenced that Dr. Doy,” concluded the Cleveland Leader, predicting that “his rescue from the fangs of slavery will gratify many.” [20] Yet such sentiments were by no means unanimous, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle condemning the “feeling of gratification” at the escape of a “convicted felon.” [21] Meanwhile, Missouri papers such as the Hannibal Messenger fumed at the escape of “the negro thief.” [22] While no retaliation or punishment ever materialized for the rescuers, a Kansan named Joseph Gardner, later feared for his safety. Writing in May 1860, Gardner reported rumors that a group of Missourians were plotting “to come and make war upon my house,” after learning that “one of the Doy rescuers is harboring fugitives.” [23]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

Later, in the aftermath of John Brown’s ill-fated Harpers Ferry raid in October 1859, many newspapers drew connections between Doy and Brown. While noting that the rescue of Doy was still “so fresh in the recollection of all readers,” an Indiana paper incorrectly but confidently concluded that Brown had been behind the daring rescue of his one-time associate. [24] Moreover, the memory of Doy’s months-old rescue led many to speculate that a similar effort was in the works to save Brown from the noose. In November 1859, rumors swirled that Doy himself was rounding up a posse “for the purpose of rescuing Old Brown from prison.” Ultimately, no such feat was undertaken, and the famous abolitionist was hanged in December. [25]

While Doy went on to publish his Narrative (1860), vividly describing his imprisonment and rescue, the fate of the freedom seekers who accompanied him remains unclear. While most of the 13 African American men, women and children captured with Doy likely found themselves on the much-dreaded journey down the Mississippi to New Orleans, at least two men managed to escape this fate. Charles Smith, the free African American cook from Pennsylvania, apparently escaped and returned home. [26]

Bill Riley also escaped in mid-February, though the 35-year-old freedom seeker remained apprehensive about the fate of his wife, whom he suspected had been returned to her slaveholder in Lexington, Missouri. Riley and his wife had escaped bondage in Missouri around September 1858. They joined Doy’s group in hopes of reaching “a freer soil in British dominion,” in the words of Lawrence abolitionist Ephraim Nute, who sheltered the freedom seeker. While Nute helped Riley move to another safe location later in March 1859, it was without his wife. For Riley, his hard-fought freedom had come at a terrible cost. [27]

In the months after his dramatic rescue, Doy, now a fugitive himself, settled in Battle Creek, Michigan. After Missouri abolished slavery in January 1865, Missouri’s Republican Governor Thomas Fletcher officially pardoned the fugitive abolitionist on February 11, 1865. Yet it would not be Doy’s last brush with the law. In 1869, the self-anointed doctor was convicted of carrying out an abortion on a woman in Battle Creek. Facing jail time, Doy allegedly consumed a “large dose of morphine.” The former abolitionist was found lifeless in his bed on the morning of June 8, 1869, his death widely reported as a suicide. [28]

FURTHER READING

Doy published his own Narrative (1860) detailing his capture and rescue, and James B. Abbott, leader of the 10-man rescue party, later gave a widely reprinted address about the incident. Doy’s account is not entirely credible, however, since he claims repeatedly that all of the African Americans in his entourage were free, not enslaved. As the case unfolded in 1859, both Kansas and Missouri newspapers devoted considerable space in their columns to covering the failed escape and subsequent rescue, especially the Lawrence Republican (Newspapers.com). Correspondence between Lawrence abolitionists concerning their reactions to Doy’s capture and rescue, as well as information about the fate of freedom seeker Bill Riley, is available through Kansas Memory.

Recent scholarship has also touched on Doy’s capture and rescue. In her work On Slavery’s Border (2010), Diane Mutti Burke places the Doy case in the context of other “slave-stealing” episodes dating back to the early 1840s, arguing that by casting blame on white abolitionists as the instigators of slave escapes, Missouri slaveholders could avoid grappling with the reality of enslaved peoples’ discontent and innate desire for freedom. Lowell Soike’s Busy in the Cause (2014) focuses on the recurring and often violent clashes over slavery in the region, spotlighting Brown’s 1858 raid into Vernon County, Missouri, and linking that episode with Doy’s subsequent capture. Kristen Epps’s Slavery on the Periphery (2016) instead emphasizes the porous nature of the Kansas-Missouri border, observing that all of the freedom seekers Doy attempted to lead to safety had already crossed the border into Kansas.

ENDNOTES

[1] Julia Louisa Lovejoy to Mr. Editor, February 28, 1859, in “Letters of Julia Louisa Lovejoy, 1856-1864,” The Kansas Historical Quarterly 16, no. 1 (February 1948): 48-53; John Doy, The Narrative of John Doy, of Lawrence, Kansas (New York: Thomas Holman, 1860), 23-24, [WEB]; Lowell J. Soike, Busy in the Cause: Iowa, the Free-State Struggle in the West, and the Prelude to the Civil War (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 102-103; 1850 U.S. Census, Wakarusa, Township, Douglas County, Kansas, Family 408, Ancestry.

[2] Doy, Narrative, 25-26; “From Our Kidnapped Friends in Missouri,” Lawrence Republican, February 17, 1859; Mary Brown to William Brown, January 30, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB].

[3] “Missouri and Slavery,” St. Louis Central Christian Advocate, February 2, 1859, quoted in Chicago Tribune, February 9, 1859.

[4] St. Louis News, quoted in Chambersburg, PA Franklin Repository, February 23, 1859.

[5] Epps, 125, 129-132; Soike, Busy in the Cause, 95-104.

[6] “Kidnapping a Felony,” Lawrence Republican, January 20, 1859; Doy, Narrative, 23, 126; Soike, Busy in the Cause, 102.

[7] Doy, Narrative, 23, 126; David Fiske, Solomon Northrup’s Kindred: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens Before the Civil War (Santa Barbara, CA Praeger, 2016), 80-81; Kristen Epps, Slavery on the Periphery: The Kansas-Missouri Border in the Antebellum and Civil War Eras (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 140-141.

[8] Soike, Busy in the Cause, 100-102; Doy, Narrative, 123; “Thirteen Negroes Captured in Kansas,” Weston, MO Argus, January 26, 1859, quoted in The Liberator, February 18, 1859; Lovejoy to Mr. Editor, February 28, 1859, in “Letters of Julia Louisa Lovejoy, 1856-1864,” 49-52; John Doy to Strong, October 19, 1854, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; “Dr. Doy of Kansas,” New York Times, March 18, 1859, [WEB]; “Who and What is John Doy?,” St. Joseph, MO Weekly West, July 31, 1859; Ephraim Nute to Unidentified, February 14, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Nute to Franklin B. Sanborn, March 22, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Soike, Busy in the Cause, 102; Harriet C. Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004), 152-159; David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 280.

[9] Doy, Narrative, 123; Epps, Slavery on the Periphery, 140-141; also see Diane Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 176-177.

[10] Doy, Narrative, 27-42.

[11] “From Our Kidnapped Friends in Missouri,” Lawrence Republican, February 17, 1859.

[12] “Thirteen Negroes Captured in Kansas,” Weston, MO Argus, January 26, 1859, quoted in The Liberator, February 18, 1859.

[13] Doy, Narrative, 50-52; St. Louis Democrat, quoted in Nashville Union and American, February 10, 1859; Nute to Unidentified, February 14, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; “From Kansas,” New York Times, September 2, 1859; Fiske, Solomon Northrup’s Kindred, 80-82.

[14] Nute to Unidentified, February 24, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Nute to Franklin B. Sanborn, March 22, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Doy, Narrative, 52-53; Epps, Slavery on the Periphery, 129.

[15] Doy, Narrative, 76-77, 88-89, 105-107; “The Trial of Dr. Doy and Son at St. Joseph,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1859, [NEWSPAPERS.COM]; “The Doy Trial at St. Joseph,” Chicago Tribune, April 1, 1859, [NEWSPAPERS.COM]; Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves, 157.

[16] Doy, Narrative, 107-115; James B. Abbott, “The Rescue of Dr. John W. Doy,” in Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society 4 (1888): 312-323, [WEB]; “Dr. Doy and His Rescuers,” St. Joseph, MO Herald, February 11, 1883; “Rescue of Dr. Doy,” Lawrence, KS Journal, July 20, 1907.

[17] Nute to Unidentified, February 14, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB].

[18] Mary Brown to William Brown, January 30, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB].

[19] “From Kansas,” New York Times, September 2, 1859; Doy, Narrative, 26, 124-126; Whitley later headed the Secret Service under the Grant administration from 1869-1875. See A.T. Andreas, History of the State of Kansas (Chicago: A.T. Andreas, 1883), 862.

[20] “Rescue of Dr. Doy–Particulars,” Cleveland Leader, July 27, 1859.

[21] “Rejoicing over the Ecape of a Convicted Felon,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 2, 1859.

[22] “John Doy Rescued from the St. Joseph Jail,” Hannibal Messenger, July 27, 1859.

[23] Joseph Gardner to George L. Stearns, May 29, 1860, Kansas Memory, [WEB].

[24] “The Late Movements of Ossawatomie Brown,” New Albany, IN Daily Ledger, October 27, 1859.

[25] Cincinnati Commercial, quoted in “Proposed Rescue of Old Brown,” Alexandria, VA Gazette, November, 11, 1859.

[26] Doy, Narrative, 50-52; St. Louis Democrat, quoted in Nashville Union and American, February 10, 1859; Nute to Unidentified, February 14, 1859; “From Kansas,” New York Times, September 2, 1859; Fiske, Solomon Northrup’s Kindred, 80-82

[27] Nute to Unidentified, February 24, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Nute to Franklin B. Sanborn, March 22, 1859, Kansas Memory, [WEB]; Doy, Narrative, 52-53; Epps, Slavery on the Periphery, 129.

[28] “Our Missouri Letter,” Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1865; “Michigan,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1869; “Suicide,” Lawrence, KS Journal, June 17, 1869; Paola, KS Miami County Advertiser, June 19, 1869; “Dr. Doy Dead and Buried,” Topeka, KS Kansas Weekly Commonwealth, February 24, 1870; Find A Grave, [WEB].

Video

Escape Attributes

Outcomes

Sources

Doy published his own Narrative (1860) detailing his capture and rescue, and James B. Abbott, leader of the 10-man rescue party, later gave a widely reprinted address about the incident. Doy’s account is not entirely credible, however, since he claims repeatedly that all of the African Americans in his entourage were free, not enslaved. As the case unfolded in 1859, both Kansas and Missouri newspapers devoted considerable space in their columns to covering the failed escape and subsequent rescue, especially the Lawrence Republican (Newspapers.com). Correspondence between Lawrence abolitionists concerning their reactions to Doy’s capture and rescue, as well as information about the fate of freedom seeker Bill Riley, is available through Kansas Memory.

Recent scholarship has also touched on Doy’s capture and rescue. In her work On Slavery’s Border (2010), Diane Mutti Burke places the Doy case in the context of other “slave-stealing” episodes dating back to the early 1840s, arguing that by casting blame on white abolitionists as the instigators of slave escapes, Missouri slaveholders could avoid grappling with the reality of enslaved peoples’ discontent and innate desire for freedom. Lowell Soike’s Busy in the Cause (2014) focuses on the recurring and often violent clashes over slavery in the region, spotlighting Brown’s 1858 raid into Vernon County, Missouri, and linking that episode with Doy’s subsequent capture. Kristen Epps’s Slavery on the Periphery (2016) instead emphasizes the porous nature of the Kansas-Missouri border, observing that all of the freedom seekers Doy attempted to lead to safety had already crossed the border into Kansas.