Participants

Route

Description

On November 8, 1861, more than 150 enslaved Missourians escaped into the camp of Brig. Gen. Joseph H. Lane's Kansas Brigade. Although Lane allowed slaveholders to search his camp, a reporter for the New York Herald attested that not a single freedom seeker had been recaptured. The 150 freedom seekers from new Springfield and others from elsewhere in western Missouri followed Lane's brigade back into Kansas, arriving on free soil on November 13.

Full Narrative

To view this full narrative with all of its embedded multi-media, please go to the 1861 Springfield Stampede post at our research blog. For a printable version, download this PDF.

DATELINE: NOVEMBER 7, 1861, SPRINGFIELD, MO

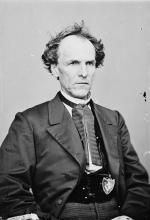

Union soldiers of the 24th Indiana Infantry cheered and sang songs as they gathered outside the headquarters of Brig. Gen. James H. Lane. It was around 9 pm on Thursday night, November 7, 1861 and the Hoosiers clamored for a speech from “Jim Lane, the Liberator,” a sitting U.S. senator, outspoken anti-slavery Republican, and commander of the Kansas Brigade. Emerging in civilian garb, Lane got right to the point. The war was about slavery, and it was high time the Union army stopped returning freedom seekers, even to loyal slaveholders in border states like Missouri. “Let us be bold––inscribe ‘freedom to all’ upon our banners.” Should the federal government order him to return freedom seekers, Lane declared to “thundering applause” that he would “break his sword and quit the field.” [1]

Reporters picked up Lane’s speech, but so too did enslaved African Americans living near Springfield, a vital crossroads in southwestern Missouri. The following night, Friday, November 8, “as if by preconcerted movement,” more than 150 enslaved Missourians escaped into Lane’s camp in a “great stampede.” Men, women, young children, and “whole families” found refuge with the Kansas Brigade. And when Unionist slaveholders came looking for them the next day, Lane kept his word. A reporter on the scene had “not yet heard of an instance in which one has been found.” [2] Another ten months would elapse before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which famously exempted loyal states such as Missouri. But early in the war enslaved Missourians were already seizing opportunities to “stampede” into Union lines, where they found growing numbers of northern soldiers willing to help them claim freedom.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

James Lane invoked the term “stampede” in his November 7 speech, arguing that it was not the Union army’s duty to “prevent [Confederates’] slaves from stampeding.” His remarks were widely reprinted by northern papers urging the adoption of more aggressive anti-slavery policies. [3] Days later, correspondents for two major New York serials, the Tribune and World, described the “great stampede” or “regular stampede” that followed on Friday night, November 8. [4]

MAIN NARRATIVE

By the fall of 1861, a Union army under Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont had moved into southwestern Missouri in an effort to clear the state of Confederate forces. In late October, Fremont’s men drove Confederates out of Springfield in Greene county and set up camp nearby. Though controversy and uncertainty over federal emancipation policy dogged Fremont’s advance. Back on August 30, the Republican politician turned Union general had made headlines by declaring martial law across the state and emancipating all enslaved people held by disloyal slaveholders. Within days, President Lincoln ordered Fremont to modify his order to conform with congressional confiscation policies. Thus it was uncertain what the Union army’s presence would mean for slavery in southwestern Missouri. Some white residents actually welcomed the columns of Union soldiers streaming into the region. Many slaveholders even avowed their loyalty, looking to the U.S. government as their best chance of protecting slavery. [5]

Though the area’s enslaved populace had good reason to welcome Lane’s brigade. The three Kansas regiments had literally blazed a path through western Missouri to link up with Fremont’s forces at Springfield, burning the town of Osceola, Missouri on September 23. Its ranks were filled with men who had lived through Bleeding Kansas during the 1850s, a period of violent conflict to determine whether Kansas would be admitted as a free or slave state. The brigade’s anti-slavery leanings were so well known that some started referring to the outfit as the “Jayhawkers,” a name given to free-state settlers during the earlier contest. And its commander also had solid anti-slavery credentials. Earlier that summer, Lane declared on the senate floor that “the institution of slavery will not survive, in any State of this Union, the march of the Union armies.” He even predicted that enslaved southerners would “get up an insurrection” as U.S. forces approached. [6]

Not only was he a vocal opponent of slavery, but Senator Lane played a key role in crafting early federal policy about how to treat freedom seekers who entered Union lines. In August 1861, Lane and fellow congressional Republicans passed the First Confiscation Act, which authorized Union forces to seize (and presumably liberate) enslaved people whose labor was being used to aid the Confederacy. This included enslaved southerners forced to labor on Confederate fortifications and work as teamsters, body servants, or cooks for Confederate troops. But when word of the law’s provisions got out, virtually all enslaved people who ran to Union lines claimed they had been coerced into providing manual labor for the Confederate government. How could Union officers sort out who had actually been forced to work for the Confederates and who had not? It was next to impossible. So on August 8, the U.S. War Department instructed commanders in the field to accept all enslaved people seeking refuge behind Union lines, keeping careful track so that loyal slaveholders could file claims later for compensation. As the historian James Oakes observes, these instructions “effectively extended the reach of the First Confiscation Act far beyond its technical limits.” [7]

Still Lane felt that federal policy did not go far enough. In early October, he grumbled that Union soldiers were protecting the plantations of the very Missouri slaveholders who had taken up “arms against the Government.” Many of his men felt the same way. Although the First Confiscation Act was a milestone, Lane and his Kansans saw it as “a weak gesture where a vigorous blow was needed,” writes the historian Chandra Manning, because it “targeted the rights of select individuals without dislodging the institution of slavery.” Lane thought “our policy in this regard should be changed,” and was not shy about expressing his point of view. [8] Although Lane’s Kansans were among the last Union troops to arrive at Springfield in late October 1861, they were at the leading edge of federal emancipation policy.

That point was made abundantly clear on Wednesday, October 30, when Lane’s three Kansas regiments arrived in Springfield to join Fremont’s larger Union force. One of Fremont’s staffers witnessed the brigade’s “motley procession” through town, with Lane at its head and about 200 African Americans following close behind, many mounted on horseback. Most had peeled off from plantations and farms in western Missouri and joined Lane’s brigade as it headed to Springfield. They quickly found work as laborers and servants, receiving wages from the government directly or from the pockets of officers and enlisted men who hired freedom seekers as personal cooks. Just as importantly, these freedom seekers would have an enormous impact on the future of slavery near Springfield. [9]

Scores of newly-freed black Missourians fanned out from Lane’s camp near Springfield over the ensuing days, alerting the local enslaved population that the Kansans were friendly to their cause. “Our colored teamsters and servants act as so many missionaries among their brethren,” wrote Chaplain H.H. Moore of the Third Kansas Infantry, “and induce a great many to come into camp.” Enslaved Missourians already behind Union lines “have become a sort of Vigilance Committee to secure the freedom of the slaves in our neighborhood,” one of Fremont’s staffers logged in his journal, referencing the black-led anti-slavery organizations that formed the backbone of the Underground Railroad before the war. Even a correspondent for the New York World marveled that “the agency of the negro servants in the army is all the machinery necessary to cause a regular stampede.” [10]

A pivotal event that helped trigger the stampede came on Thursday night, November 7, about a week into the brigade’s stay near Springfield. Soldiers congregated outside of Lane’s headquarters in the home of Major Daniel Dorsey Berry, a wealthy, pro-Confederate planter who had fled to his Mississippi plantation when Union forces approached. Berry left behind his wife Olivia and several daughters to keep watch over the family’s Springfield home and five enslaved people, while his son was off fighting for the Confederacy. From the slaveholding Berrys’ balcony, the Union general recited his support for a more aggressive emancipation policy. The Federal army, he told the assembled Hoosier soldiers, could not “crush the rebels” and at the same time “keep their slaves from stampeding.” That would require two armies––first a “treason crushing army” that would defeat Confederates and restore the Union, and a second “slavery restoring army” that would follow “about ten miles in the rear.” Lane remarked that he wanted to “let slavery take care of itself”––a misleading claim at best, since his soldiers were actively helping freedom seekers and Lane himself was privately reminding fellow officers of his earlier prediction that slavery “would perish with the march of the Federal armies.” [11]

The “great stampede” of more than 150 African Americans occurred the next evening, on November 8. But on the night of Lane’s speech five enslaved people escaped from the Berry household, within earshot of the Union general and undoubtedly encouraged by the tone of his remarks. Olivia Berry and her daughters, despite their likely Confederate sympathies, had stepped outside to listen to Lane’s speech. When they returned later that evening, they were “astounded to find that all the negroes in the family had embraced the opportunity afforded by their brief absence to run away!” The next morning the women fumed at “the melancholy necessity of preparing their own breakfast.” Furious at their uninvited guest, the Berry women refused to serve Lane breakfast the following morning. [12]

The mass escape that occurred on Friday night, November 8, was probably motivated as much by Lane’s speech as the imminent withdrawal of Union troops from Springfield. On November 2, President Lincoln had replaced General Fremont with Maj. Gen. David Hunter. In the same stroke, Lincoln advised Hunter to withdraw from his advanced position at Springfield and divide his force between Sedalia, located more than 110 miles to the north, and Rolla, Missouri, some 100 miles to the northeast. As part of the plan, Lane’s brigade was set to return to Kansas. Many enslaved Missourians must have realized that time was running out to claim their freedom. Lane’s Kansans would leave Springfield the next day, Saturday, November 9. [13]

Before Lane’s brigade decamped from Springfield, slaveholders arrived in large numbers and scoured the camp for the freedom seekers. Many of the enslavers identified as Unionists and anticipated that their vows of loyalty would establish their right to re-enslave freedom seekers. Diplomatically, Lane towed the official line, insisting that “my brigade is not here for the purpose of interfering in anywise with the institution of slavery.” His soldiers would “not become negro thieves nor shall they be prostituted into negro-catchers.” He invited slaveholders to “find your slave; if he is in my camp you can take him, if he is willing to go.” But few enslaved people would willingly reenter captivity, and soldiers collaborated with freedom seekers to conceal and protect them from forcible recapture. As Chaplain Moore of the Third Kansas wrote, “it cannot be denied that some of our officers and soldiers take great delight” in aiding freedom seekers, “and that by personal effort and otherwise, they do much towards carrying it on.” Reports suggested that none of the freedom seekers were recaptured. [14]

AFTERMATH

An estimated 150 enslaved Missourians from Springfield marched out of town with Lane’s brigade on November 9. However, the large number of freedom seekers quickly strained the brigade’s rations. On November 12, near Lamar, Missouri, Lane detailed three regimental chaplains, H.H. Moore of the Third Kansas, Reeder Fish of the Fourth Kansas, and Hugh Dunn Fisher of the Fifth Kansas, to take command of the freedom seekers and escort them to Fort Scott, Kansas. Not only were they to provide a safe conduit armed with just a “load of old muskets” and no ammunition, but the three chaplains were to “superintend the entire business of seeing them located” upon arriving on free soil in Kansas. Moore’s headcount enumerated 218 enslaved Missourians in a wagon train that spanned over a mile in length. The vast majority of these men, women, and children had fled from near Springfield. Some clung tightly to “a large amount of household furniture” they had taken during their flight. And they were clearly anxious to leave Missouri. During one brief stop, an enslaved woman approached Chaplain Moore and gently prodded him to keep the column moving. “Day is breaking, see,” she said, gesturing to the east. [15]

The so-called “Black Brigade” crossed into Kansas on Wednesday, November 13. Chaplains Moore and Fisher portrayed the arrival in biblical terms. Moore likened “the cheers and shouts” the freedom seekers let loose upon crossing into Kansas to “the shouts of Israel after the passage of the Red Sea.” It was, he declared with no lack of hubris, “the most remarkable exodus of slaves to a land of freedom, that has occurred since the time of Moses.” Once in Kansas, the three chaplains hired out freedom seekers to Kanas farmers willing to pay them wages. “Thus far they have been taken care of,” wrote one Kansan, “as the farmers needed help and hundreds if not thousands are now employed in harvesting.” But he worried that after harvest many of the freedom seekers would find themselves out of work and overwhelm the antislavery stronghold of Lawrence. “There is not an intelligent slave in Mo., but knows where Lawrence is and we shall have them here by thousands,” he wrote, pleading for donations from eastern abolitionists to help feed and clothe the freedom seekers over the winter. [16]

They also gave the freedom seekers new names. “We changed their names from the old plantation names to those of Northern significancy,” attested Fisher, who claimed it was “to prevent the possibility of their being returned to slavery.” Moore recalled renaming one enslaved man who went by Daniel Bonham. Bonham was the surname of his slaveholder, so Moore renamed him Daniel Webster on the spot. Similarly, Moore renamed another family of freedom seekers Fisher, as a tribute to his fellow chaplain. What the freedom seekers thought of this practice is hard to determine, though they may not have appreciated the white soldiers arbitrarily assigning them new names. [17]

The column’s arrival elicited considerable attention from Kansas newspapers, which connected it to the larger debate over a more aggressive federal emancipation policy. Editors wryly observed that the Kansas soldiers’ “favorite pastime is raking the n––rs as they go.” Although “we never fancied the idea of having free negroes colonized among us,” one white Kansan took solace in the fact that “wherever our armies march… they will leave the traitors n––rless.” [18]

Back in Springfield, slaveholding Unionists chafed that Federal forces had abandoned the town even as they groaned loudly about the flight of freedom seekers to Lane’s brigade. Within days Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch recaptured Springfield. A committee of Unionists from southwestern Missouri appealed to the Union high command to return Federal troops to the vicinity. Although McCulloch withdrew to Arkansas after a few days, they claimed that 3,000 to 5,000 loyal white Missourians had been forced to flee their homes, fearing retribution from Confederates. McCulloch, however, picked up on growing tensions within the region’s Unionist populace during his brief stay in Springfield. Federal forces had “greatly injured their cause by taking negroes belonging to Union men,” McCulloch eagerly reported back to Richmond. [19]

Some of the freedom seekers who joined Lane’s column went on to play a critical role in the Union war effort. David Ware may not have been in Springfield to hear Lane’s speech on November 7, but he was among those who followed the Kansas chaplains to freedom. Ware had been born into slavery in Cooper county, Missouri in 1839, and by 1861 he was enslaved near Greenfield, some 40 miles northwest of Springfield. Aged 22, Ware was married and father to a two-year-old child. But his wife and child were forced by their slaveholder to relocate to Springfield. She escaped from there in September, making her way on foot back to Greenfield. Reunited, in November the family linked up with the column of freedom seekers guided by Chaplains Moore, Fish, and Fisher and journeyed to Kansas. Ware served in the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry, and upon discharge went to work as a janitor at the Kansas state capitol until his death in 1888. [20]

FURTHER READING

The most detailed accounts of the Springfield stampede were penned by correspondents of the New York Tribune and World. [21] Numerous reports of the so-called “Black Brigade” and its march from Springfield were recorded in Kansas papers afterwards. The two leading eyewitness accounts of the expedition were composed by Chaplains Moore and Fisher. Days after arriving in Kansas, Moore wrote a letter to the Lawrence Republican, and decades later Fisher authored a memoir in which he detailed the column’s movement through western Missouri. [22]

Historians have largely overlooked the specifics of the November 8 stampede, though several scholars have explored the resulting movement of freedom seekers to Kansas. Bryce Benedict’s history of the Kansas Brigade, Jayhawkers (2009), briefly notes that Lane’s brigade had become “a magnet” for freedom seekers while near Springfield, before recounting the return trip to Kansas based upon Moore and Fisher’s accounts. Ian Michael Spurgeon also references the movement of freedom seekers from Springfield to Kansas in his study of Kansas’s U.S. Colored Troops. Kristen Epps highlights the episode as part of a broader trend of military chaplains assuming “an active role in shepherding contrabands to safety.” [23]

Other works help contextualize the status of slavery in the loyal border states during the war’s first year. Chandra Manning places the Union rank-and-file at the vanguard of emancipationist sentiment in her book What This Cruel War Was Over (2007). She argues that between August-December 1861, Union soldiers came to see slavery as a stumbling block to winning the war, and “championed the destruction of slavery a full year ahead of the Emancipation Proclamation, well before most civilians, political leaders, or officers.” Although she does not describe the Springfield stampede, Manning notes that Lane’s brigade “paid no attention to official distinctions drawn by the First Confiscation Act, and instead actively liberated slaves and intimidated their owners” along its path through western Missouri. In Freedom National (2013), James Oakes takes stock of Union soldiers who “were clearly cooperating with the slaves” in loyal border states, but stresses the role of Republican policymakers in promulgating anti-slavery policies that they believed would chip away at slavery, even in regions that had remained in the Union. [24]

[1] “Jim Lane’s Speech at Springfield, Missouri,” Junction City, KS Smoky Hill and Republican Union, November 28, 1861; “Gen. Lane at Springfield, Mo.,” Washington, D.C. National Republican, November 30, 1861, [WEB].

[2] “Important from Missouri,” New York Tribune, November 18, 1861; “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861.

[3] “Jim Lane’s Speech at Springfield, Missouri,” Junction City, KS Smoky Hill and Republican Union, November 28, 1861; “Gen. Lane at Springfield, Mo.,” Washington, D.C. National Republican, November 30, 1861, [WEB]; “The War and Slavery,” Springfield, MA Republican, November 13, 1861; “Speech of Gen. Lane,” Boston Liberator, November 29, 1861.

[4] “Important from Missouri,” New York Tribune, November 18, 1861; “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861.

[5] Allan Nevins, Fremont: Pathmarker of the West (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1939, rpt. 1955), 550, 657; On Fremont’s August 30 order, see James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 156-159.

[6] Bryce Benedict, Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James H. Lane (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009); Lane quoted in Oakes, Freedom National, 116, 196.

[7] Oakes, Freedom National, 122-139.

[8] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), series 2, vol. 1, 771-772, [WEB]; Chandra Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 46.

[9] [William Dorsheimer], “Fremont’s Hundred Days in Missouri, III,” Atlantic Monthly 9:53 (March 1862): 377, [WEB]. The staffer was William Dorsheimer. For identification as the author, see Benedict, Jayhawkers, 129.

[10] H.H. Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861; Dorsheimer], “Fremont’s Hundred Days in Missouri, III,” 377, [WEB]; “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861.

[11] Official Records, series 2, vol. 1, 772, [WEB]; Benedict, Jayhawkers, 293, n10; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Campbell Township, Greene County, MO, Ancestry; “Major D.D. Berry, Veteran of Many Battles, Succumbs,” Springfield, MO News-Leader, March 23, 1915; “Jim Lane’s Speech at Springfield, Missouri,” Junction City, KS Smoky Hill and Republican Union, November 28, 1861; “Gen. Lane at Springfield, Mo.,” Washington, D.C. National Republican, November 30, 1861, [WEB].

[12] H.H. Moore diary entries for November 7-8, 1861, quoted in Benedict, Jayhawkers, 293, n10.

[13] Nevins, Fremont, 657; Benedict, Jayhawkers, 156.

[14] Official Records, series 2, vol. 1, 772, [WEB]; H.H. Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861; Oakes, Freedom National, 169, 176-177; “Important from Missouri,” New York Tribune, November 18, 1861; “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861.

[15] Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861. The estimate of 150 who fled near Springfield comes from the correspondent for the New York World. His figure pertained to Friday night alone. In total, he claimed that about 500 enslaved people had joined Lane’s column since it entered Missouri earlier that fall. See “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861. Note that the wagon train of 218 freedom seekers were not all the black Missourians who had joined Lane’s brigade. Many freedom seekers stayed in the ranks and were employed as cooks and body servants by officers, messes, and individual soldiers, or as laborers on the federal government’s dime.

[16] John B. Wood to George L. Stearns, November 19, 1861, Kansas State Historical Society, available online through Civil War on the Western Border, Missouri Digital Heritage, [WEB]; Hugh Dunn Fisher, The Gun and the Gospel: Early Kansas and Chaplain Fisher (Chicago and New York: Medical Century Company, 1899), 166-168, [WEB]; Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861; “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861.

[17] Fisher, The Gun and the Gospel, 166-168, [WEB]; Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861.

[18] White Cloud, KS Chief, November 28, 1861; Junction City, KS Smoky Hill and Republican Union, November 28, 1861.

[19] Official Records, series 1, vol. 8, 370-371, 686, [WEB].

[20] “David Ware,” Topeka, KS Daily Commonwealth, September 11, 1888.

[21] “Important from Missouri,” New York Tribune, November 18, 1861; “From Gen. Hunter’s Command,” New York World, November 19, 1861.

[22] Moore to Friend Speer, November 19, 1861, in “The Black Brigade,” Lawrence, KS Republican, November 21, 1861; Fisher, The Gun and the Gospel, 166-168, [WEB].

[23] Benedict, Jayhawkers, 156-159; Ian Michael Spurgeon, Soldiers in the Army of Freedom: The 1st Kansas Colored, the Civil War’s First African American Combat Unit (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 41-42; Kristen Epps, Slavery on the Periphery: The Kansas-Missouri Border in the Antebellum and Civil War Eras (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 166-167, see post.

[24] Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over, 45-46; Oakes, Freedom National, 169.

Escape Attributes

Outcomes

Sources

The most detailed accounts of the Springfield stampede were penned by correspondents of the New York Tribune and World. Numerous reports of the so-called “Black Brigade” and its march from Springfield were recorded in Kansas papers afterwards. The two leading eyewitness accounts of the expedition were composed by Chaplains Moore and Fisher. Days after arriving in Kansas, Moore wrote a letter to the Lawrence Republican, and decades later Fisher authored a memoir in which he detailed the column’s movement through western Missouri.

Historians have largely overlooked the specifics of the November 8 stampede, though several scholars have explored the resulting movement of freedom seekers to Kansas. Bryce Benedict’s history of the Kansas Brigade, Jayhawkers (2009), briefly notes that Lane’s brigade had become “a magnet” for freedom seekers while near Springfield, before recounting the return trip to Kansas based upon Moore and Fisher’s accounts. Ian Michael Spurgeon also references the movement of freedom seekers from Springfield to Kansas in his study of Kansas’s U.S. Colored Troops. Kristen Epps highlights the episode as part of a broader trend of military chaplains assuming “an active role in shepherding contrabands to safety.”

Other works help contextualize the status of slavery in the loyal border states during the war’s first year. Chandra Manning places the Union rank-and-file at the vanguard of emancipationist sentiment in her book What This Cruel War Was Over (2007). She argues that between August-December 1861, Union soldiers came to see slavery as a stumbling block to winning the war, and “championed the destruction of slavery a full year ahead of the Emancipation Proclamation, well before most civilians, political leaders, or officers.” Although she does not describe the Springfield stampede, Manning notes that Lane’s brigade “paid no attention to official distinctions drawn by the First Confiscation Act, and instead actively liberated slaves and intimidated their owners” along its path through western Missouri. In Freedom National (2013), James Oakes takes stock of Union soldiers who “were clearly cooperating with the slaves” in loyal border states, but stresses the role of Republican policymakers in promulgating anti-slavery policies that they believed would chip away at slavery, even in regions that had remained in the Union.