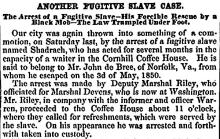

ANOTHER FUGITIVE SLAVE CASE.

The Arrest of a Fugitive Slave--His Forcible Rescue by a Black Mob--The Law Trampled Under Foot.

Our city was again thrown into something of a commotion, on Saturday last, by the arrest of a fugitive slave named Shadrach, who has acted for several months in the capacity of a waiter in the Cornhill Coffee House. He is said to belong to Mr. John de Bree, of Norfolk, Va., from whom he escaped on the 3d of May, 1850.

The arrest was made by Deputy Marshal Riley, who officiated for Marshal Devens, who is now at Washington. Mr. Riley, in company with the informer and officer Warren, proceeded to the Coffee House about 11 o'clock, where they called for refreshments, which were served by the slave. On his appearance he was arrested and forthwith taken into custody.

The hearing was before Hon. G.T. Curtis, U.S. Commissioner, who also issued the warrant for his arrest. Seth J. Thomas, Esq., of this city, appeared as the empowered attorney to prosecute the claim, and Messrs. Sewall, E.G. Loving, Dana, and others, of this city, for the defense.

At the request of the defense, Mr. Thomas read a series of documents in his possession, as the legal evidence to substantiate the claim--consisting of De Bree's original application before Richard H. Baker, Judge of the U.S. Circuit Court of Norfolk; the certificate of John Williams, clerk of said Court, that De Bree is a citizen of Norfolk, and made his claim before the Court, and that the Judge's signature was genuine, &c.; certain papers, tracing the ownership of the alleged fugitive from one party to another; and sundry powers of attorney for his apprehension, prosecution, transportation, and restoration to the present claimant.

At the conclusion of the reading of the documents, the Commissioner postponed the further consideration of the case to Tuesday next, at 10 A.M.

The counsel for the prisoner remained for consultation sometime--till nearly 2 o'clock. The purport of all this, it is hinted, was to "facilitate business"--and the issue of events fully proved that business was somewhat facilitated. One by one the counsel left the Court-room, and as the last of them, Mr. Davis, was departing, a band of colored men rushed into the room, surrounded the prisoner, and at once escorted him down stairs into the street, and thence to a place said to be provided for him in Belknap street.

The officers of the Court room were overpowered. The movement on the part of the crowd--a perfect stampede, had all the celerity and completeness of a concerted plan, which it is openly talked, was the case. Whether it really was so or not; it is quite certain that it took place at the very and only time it could have been done.

Daily Bee of Monday.

This case has occasioned considerable excitement. Deputy Marshal Riley has published a statement, blaming the Mayor and Marshal Tukey for not lending such assistance as to prevent the rescue of the Fugitive. Both of these functionaries have published cards.

The Mayor says:--

On Saturday last, between the hours of 11 and 12 o'clock, Mr. Riley came to my office in the City Hall, and said to me.--"We have got a negro, and I thought I would call and let you know." I received the information as a kindly hint to look out for street disturbances. He made no request whatever for assistance, nor did he intimate in any way that he wanted any, or that he had any apprehension of a rescue. After a few unimportant remarks he retired. I immediately sent for the Marshal, and directed him to preserve order around the Court House, to prevent obstructions to proper communication therewith, of course including (as all such orders do) the protection of officers in charge of prisoners, while getting to or from the building. I remained in my office an hour and a half after giving these directions, but received no further communication on the subject from any one. The Police, within my knowledge, have never been called upon to attend the Courts of the State or United States, and, as I have already stated, no request was made to me for such assistance in the present case. Knowing that the Marshal of the United States has its own officers, and that he is authorized to appoint as many deputies, or call to his assistance as many individuals as the occasion may require--knowing, also, that the Sheriff, together with deputies and constables, are stationed in the Court House, I had not the shadow of suspicion that Mr. Riley was wanting in ample means to retain his prisoner against unarmed assailants.

Marshal Tukey remarks:--

I learn, and I believe it to be true, that Mr. Riley said he did not want any others than those he had employed, to remain in the court room, and added that, "We can take care of the man," and also at the time the rush was made, he was walking backwards and forwards across the court room, and made no resistance whatever at the door, or as the negroes passed by him.

In conclusion, allow me respectfully to say, that in the Ordinance creating the office of City Marshal, I do not find that he is to do the work of the United States Marshal; and if it is the wish of the City Government to have me do it, they have only to pass the order, and I will arrest the Fugitives and keep them or I will resign.

"Another Fugitive Slave Case," Boston (MA) Recorder, February 20, 1851, p. 2.