Missouri and Slavery.

[From the St. Louis Cent. Christian Advocate, Feb. 2d.]

One of the most striking and significant facts connected with Missouri is the change that is constantly going on as it regards the relative portion of the white and colored population in reference to numbers and social position. Scarcely a week passes without witnessing the emigration of hundreds of slaves to the South. Various and numerous are the causes for this unprecedented movement. We can only enumerate a few of the principal elements involved.

One of the principal causes, in our judgement, is that it is demonstrated as clearly as any of the problems of Euclid, that so far as Missouri is concerned, white labor is far more profitable than slave labor. A stranger coming to St. Louis would be surprised to find that in the hotels, barber shops, and on the levee, that the parties employed are generally whites--seldom do you find a colored person performing this kind of labor.

We remember, when we first came to this city, being taken by surprise to find at the hotel where we put up, that there was not so much as one colored person. When we went to the barber shop, we expected, as a matter of course, to meet with one of the sable profession, but we were disappointed. A correct conception may be formed of their relative position, from the fact that the slave population of the city only amounts to 1,000, and as it regards this number, many of them are a burden to their owners.

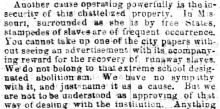

Another cause operating powerfully is the insecurity of this chattelized property. In Missouri, surrounded as she is by free States, stampedes of slaves are of frequent occurrence. You cannot take up one of the city papers without seeing an advertisement with its accompanying reward for the recovery of runaway slaves. We do not belong to that extreme school designated abolitionism. We have no sympathy with it, and just name it as a cause. But we are not to be understood ad approving of that way of dealing with the institution. Anything like violent interference with it only serves, in our judgment, to increase the difficulties in the way of emancipation. But at the same time the difficulty of holding slaves, under such circumstances, is certainly one of the most powerful principles in operation to thin the State of slaves.

But perhaps of all these causes in operation, one of the most potent is the deep, the firm, the settled obsolute conviction that Missouri is speedily destined to be a free State. There are principles in operation that must ultimately work out this result. There is the song undercurrent of feeling that pervades the depths of the American mind in favor of freedom obtaining an embodiment, and must soon gather such force as to sweep every vestige of slavery from the land. In no part of this vast continent is this undercurrent rising to the surface so rapidly as in Missouri. Our friends at a distance may rest assured that the day of freedom in Missouri is not far distant, and when that day arrives, as a Church, we shall have the consolation to know that we have mingled in freedom's battle, that we have carried the pure, the everlasting gospel, that proclaims liberty to the captive, into every part of the State. Amidst persecution and death we have stood to our post, stood while assailed by all the malignity and fanaticism that a political and ecclesiastical zeal could inspire. But what is more trying than all the outward pressure and opposition that has been brought to bear upon us, has been the cold shoulder turned towards us by some of these small friends--small in every sense of the term--destitute of minds capable of grasping the mighty principles at issue. But we thank God we still live, and in every department of our vast field the work is extending, and already the notes of victory are heard.

"Missouri and Slavery," Chicago (IL) Tribune, February 9, 1859, p. 2