Kentucky Negro Exodus

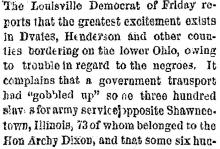

Kentucky Slaveholders have held on to their chattels like “death to a dead nigger,” but the inexorable war of rebellion is now fast breaking the chains of the “peculiar institution” even in Kentucky. The Louisville Democrat of Friday reports that the greatest excitement exists in Davies, Henderson and other counties boarding on the lower Ohio, owing to trouble in regard to the negroes. It complains that a government transport had “gobbled up” some three hundred slaves for army service opposite Shawneetown, Illinois, 73 of whom belong to the Hon Archy Dixon, and that some six hundred slaves had collected at Owensboro’ a potion of whom had enlisted in the Federal army. Considerable excitement existed and fears we entertained of a negro insurrection. At Owensboro’ the stores were closed, and business had been suspended for several days.

This is the portion of Kentucky where Forrest and his raiders were recently entertained and furnished with supplies by rebel sympathizers, and committed all sorts of conscription and outrage on Union men and their families. The present sufferers in the negro line have little or no claim on loyal sympathy.

A Washington dispatch to the Tribune says:

Adj-General Thomas will be in Kentucky next week, and two silver eagles will take an unusually high flight and then the slaves of Kentucky will be gathered in by this great recruiter with a rake that will not leave a country unvisited. The epoch of pro-slavery bluster, Border State sneaking and military slave-driving is at an end.

The negroes of Kentucky have got to fight for the Union. Gen. Thomas goes down with plenary powers, and carries in his pocket, to start with, the organization of three regiments, the names of qualified officers who have passed Casey’s Board. Sixteen regiments of Kentucky blacks will swell the army ranks in a few weeks.

The Cincinnati Commercial of the 4th has the following gratifying article on the Kentucky exodus:

Within a few days the negroes of Kentucky have become impressed with the idea that the road to freedom lies through military service, and there has been a stampede from the farms to the recruiting offices. The able-bodied blacks are turning out almost unanimously, and the women and children are disposed to go with the crowd. The consequence is, the railroads of the States have not the capacity to transport the negroes who are finding their way to the United States camps. The white people of Kentucky are taking this extraordinary commotion among the negroes very cooly, looking upon it as one of the phenomena of the times, and acquiescing in it as a part of the drift of destiny. Slave property has been recognized in Kentucky as very precarious its nature, ever since the Southern fanatics insisted that sectional difficulties should culminate in war. The negroes have not been in good working condition for some time, and their rush for the army is not as serious a matter for the agricultural interests of the State as might be expected. Then they are relieving the State of the draft, suddenly and forever, for enough of them are swarming to meet all probable calls in the future. If the Government chooses to accept black men for soldiers, and the blacks want to go, and the whites don’t, it is absurd for the whites to complain of the policy that practically exempts them and receives an inferior article in full consideration of all demands. The uprising, if we may so call it, of the negroes of Kentucky, now in progress, is one of the most remarkable and significant events of the war.

"Kentucky Negro Exodus," Cleveland (OH) Daily Herald, June 6, 1864, p. 4.