"Indemnity for the Past and Security for the Future."

There is little danger that the Union men of the South, when they come into power, will err on the side of excessive clemency towards the rebels. From what is going on in Kentucky, the vigor of whose Unionism has been much distrusted, we may judge somewhat as to the feeling of the Union men of the other states towards their relentless persecutors, and by what means they will satisfy their just desires for retribution. The people in some of the most loyal counties of Kentucky oppose the return of the rebel prisoners who went from among them, and who now profess repentance for their disloyalty and ask to be allowed to go to their homes, on taking the oath of allegiance. The Union men very properly object to being exposed to such dangerous neighbors, and especially to allowing them to vote and get control of the very government they have just been attempting to destroy. The Kentucky legislature, too, while Congress is puzzled to discover some way in which it may legally punish and mulct the rebels, has gone straight forward and adopted the eminently practical measure of disfranchising every citizen of the state who shall enlist in the rebellion, or remain in it, after the passage of the bill, and forbidding the restoration of the rights of citizenship to any such person except by special act of the legislature. Unfortunately, Kentucky has a governor who is a traitor at heart, and he has vetoed the bill, under the pretense that it encroaches upon the prerogatives of the executive and judiciary. He wants the power to pardon the traitors in his own hands, and there is no doubt that he would use it liberally. Whether the legislature will pass the act over his veto is doubtful, but its first passage throws much light on the point we are considering––the disposition of the Union men of the South to punish the rebels and destroy their power in every possible way. It could hardly be otherwise, for there will be no safety for loyal men in the South until the political influence of the men who have conspired against the Union is completely broken down. The restoration of the insurgent states to the Union by placing their loyal men in possession of the state governments, thus gives the most ample security for the future, and we need trouble ourselves with no appalling visions of Jeff Davis and his fellow criminals again in the national councils. They can never again have any political existence, even in their own localities, and it is the consciousness of this that will nerve them to resist to the last, so long as they can get a regiment of their deluded followers to stand between them and the halter.

Undoubtedly there will be a degree of magnanimous and political forbearance exercised towards the masses of the southern people, who have been misled into rebellion. We cannot hang them all, as we shall hang the conspirators whose wicked ambition has covered the land with mourning and blood. But the consideration of the extent and methods of this leniency is now premature. After the last rebel army is beaten and dispersed, and the power of the Union is recognized and obeyed in every state, it will be time enough to consider who shall be pardoned and upon what terms. This is not a matter for negotiation with revels, but of our, unmerited grace on the part of the government, to be extended only so far as seems consistent with its own safety and the future peace of the Union. All idea of negotiation, compromise or conciliation, is excluded by the nature of the case. Government does not make terms with criminals and outlaws. It vindicates its right and ability to punish their crimes, and it pardons only when the true ends of government can thus be best promoted. Those short-sighted politicians in the North who suppose they can get up a party of compromise, and admit to the privilege and power of American citizens the wretches whose hands are still red with the blood of thousands of loyal men, mistake alike the tempe[r] and prudence of the American people.There will be no settlement which does not include the punishment of the guilty authors of all this mischief, and the most ample security against any future attempt to overthrow the government.

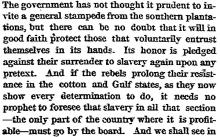

In the way of indemnity for the past not a great deal is to be expected. Congress seems to be at a loss to hit upon a practical and constitutional mode of reaching the property of the traitors and converting it to the use of the government. If anything can be secured in this way towards paying even a small portion of the expenses of the war, it is just and right that it should be. The limited confiscation act passed in August last can be made to accomplish something. It confiscates all property used "in aiding, abetting or promoting the rebellion," and declares free all slaves employed in any manner in the war upon the government. Loyal citizens, filing information of property subject to confiscation, are entitled by the act to one-half of its value. This gives the robbed and maltreated Unionists of the South a means of securing some indemnity for their own personal wrongs, as well as assisting in the just punishment and degradation of the rebels, and we may be certain that advantage will be taken of it wherever the power of government is so re-established as to make it possible and safe to enforce the law. And, notwithstanding the fierce clamor for immediate and general emancipation, it is already apparent that by the progress of our armies the government is getting emancipated negroes on its hands quite as fast as it can provide for them. The government has not thought it prudent to invite a general stampede from the southern plantations, but there can be no doubt that it will in good faith protect those that voluntarily entrust themselves in its hands. Its honor is pledged against their surrender to slavery again upon any pretext. And if the rebels prolong their resistance in the cotton and Gulf states, as they now show every determination to do, it needs no prophet to foresee that slavery in all that section––the only part of the country where it is profitable––must go by the board. And we shall see in less than six months, and the slaveholders of the borders states will see, that it is for their interest to accept the help of the general government in disposing of their negroes––for their interest in fact to be rid of them at all events, with or without help.

"Indemnity for the past and security for the future," then, require among the essential conditions, the rigid punishment of the chief traitors––the men on whose heads rest the unpardonable guilt of this monstrous rebellion––the disfranchisement of all who have taken up arms against the Union, or in any way voluntarily assisted in the rebellion; the confiscation of property and the emancipation of slaves used in the rebellion, and the limitation and removal of slavery by all legal and practicable means. these are but outlines of the work to be done; the details can only be fixed as events bring the proper moment for action in each. But, substantially, all this is to be done, and the loyal millions who have expended their blood and treasure in the suppression of this gigantic rebellion will consent to nothing less.

" 'Indemnity for the Past and Security for the Future'," Springfield (MA) Republican, March 19, 1862, p. 2.