From the Chicago Post.

THE AFRICAN EXCITEMENT.

Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad.

Since the arrest and return of five fugitive slaves by the United States Marshal on the 3d inst., the climate of Africa has existed in Chicago. The excitement has been hot. The negroes and their white friends, who resist the execution of the Fugitive Slave law, have been in that state of temperature at which the mild beverage they usually imbibe loses its quiescent state in that of ebullition. In other words, boils. Although the bubbling has not appeared in a very active state on the surface, yet just beneath, the agitation has been, deed, startling and slightly terrific. We have taken some pains to investigate the subject, in order to present before our readers some facts in regard to the negro excitement existing in this city during the last few days.

CAUSES OF THE ALARM.

The arrest of five fugitive slaves on the morning of the 3d, was the primary cause of alarm among the Africans in Chicago, of whom the larger part are runaway slaves. Intelligence of the arrest came among them like a thunderbolt out of a clear sky. For ever ten years their sky had been clear, excepting a mere speck, now and then, in the shape of a warrant issued for some fugitive, but never executed––or if executed, in such a manner that the fugitive had ample opportunity to escape. The last previous occasion when a bona fide attempt was made by a Marshal to execute the law, was ten years ago, when George W. Meeker, now dead, held the office of commissioner. The warrant in that case described the fugitive with great particularity, as a copper-colored negro, and to make the identification still stronger, the negro most positively asserted that the claimant was his master. But. Mr. Meeker, (albeit a Democrat,) said in judgement he could not upon his conscience decide that the person claimed as a fugitive slave was a "copper-colored negro." That decision passed into a precedent, upon which Africa has reposed in fancied security ever since.

But the successful arrest and extradition of no less than five fugitives on the third, opened their eyes to new danger. The declaration of Long John that fugitives were no longer safe here tended greatly to increase the alarm. Every idle rumor was magnified by the ignorant, credulous and timid blacks into a horror of untold dimensions. At one time they believed the Marshal had in his hands fifteen additional warrants for fugitives; at another, the story was that there were six hundred Missourians in the city looking for their lost negroes. Indeed, such has been the terror among fugitives during the last three or four days, that in every strange face they beheld a slave owner and in every lamp-post an officer. The stampede for Canada became general, with all who could get away.

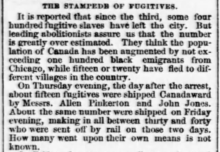

THE STAMPEDE OF FUGITIVES.

It is reported that since the third, some four hundred fugitive slaves have left the city. But leading abolitionists assure us that the number is greatly over estimated. They think the population of Canada has been augmented by not exceeding one hundred black emigrants from Chicago, while fifteen or twenty have fled to different villages in the country.

On Thursday evening, the day after the arrest, about fifteen fugitives were shipped Canadaward by Messrs. Allen Pinkerton and John Jones. About the same number were shipped on Friday evening, making in all between thirty and forty who were sent off by rail on those two days.How many went upon their own means is not known.

On Friday afternoon, a propeller was chartered to take fugitives across the lake to Grand Haven, and thirty were shipped in this manner yesterday morning, by Deacon Carpenter.

Many of the fugitive sold everything they possessed at a sacrifice; others left all their goods behind. One person, a drayman, left a horse and dray, and all his household wares, taking the train for Canada, with only his wife and children. This person had read the advice given by Long John, and believing him to be the colored person's friend, acted upon it, not waiting to let any grass grow under his feet.

In some cases, families have been separated, as where they wife or husband was a slave and the other free. A free negro named Johnson, whose wife is a slave, sent her and their offspring on board Deacon Carpenter's propeller for shipment to Canada, but before the propeller left port, it was ascertained that her old master was dead. She was accordingly brought back and restored to the arms of her husband.

The peculiar friends of the blacks exerted themselves to allay the excitement and quiet their fears. To this end they have investigated the different rumors, and finding them to be groundless, explained the matter as well as they could to the dull comprehension of the negroes. Persons were appointed to find out whether any more such writs were in the hands of the Marshal, who reported the groundlessness of rumors upon that score. But notwithstanding all they could do the excitement still continued intense.

On Friday evening, the blacks held a meeting in their chapel on Jackson street, appointed a vigilance committee and adopted measures in connection with their white friends, to arm all the fugitives who remain in the city. The business of collecting money and purchasing revolvers was actively prosecuted yesterday.

THE U.G.R.R.––HOW IT WORKS.

We are informed by leading agents of the underground railway that during the last six months more negroes have escaped from slavery and reached Chicago than during a like period at any previous time. The reason of this is said to be that the facilities for their escape have been better. Nearly all of them have come from the neighborhood of St. Louis, where some of the most active and expert agents of the road reside. Winter is the most favorable time for operations, as then the fugitive can cross the river on the ice in the night, and not be liable to any unpleasant questioning on the ferry-boat. Once in Illinois, he takes the first train for Chicago. If he has money to pay his fare he can generally get through without much difficulty; if he has no money, he is liable to be put off at the next station. But by the next train he proceeds ot another station, before being put off, and so in the course of a week he reaches Chicago.

But it not unfrequently happens, though he may have no money, that the fugitive comes through with great dispatch. About six weeks ago, a piano box was received at the freight depot of the Chicago and St. Louis Railway in this city, properly directed and labeled "This side up with care." It was delivered to the proper party, who, having removed to a convenient place, opened it and let the negro out. He was found to be in good condition, but complained of being "hungry ad de debble!"

In like manner a negro was released, some weeks ago, from a sugar hogshead, shipped to this city from St. Louis.

These slave escapes are not always without an air of romance, to one with a vivid imagination and not particular as to color. Shortly before the escape of Eliza Grayson from Mr. Nuckles, in Nebraska, a young and handsome quadroon boy applied on board a Missouri river steamboat for a situation as table waiter. As the boy came on board above the Missouri line, the stewart said to his conscience, "of course this darkey is free, and as I want more help, and he appears to be a bright boy, I'll hire him." So the boy went joyfully into the cabin, and the steamboat proceeded down the river. At St. Louis the boy left the boat and succeeded by dint of his good looks and intelligence in obtaining a situation in the cabin of a steamer bound for the Illinois river.

The boat carried him to Lasalle, where, receiving his wages, he left and shipped as cook on a canal boat for Chicago. Here the handsome quadroon boy found a brother, who (it is to be presumed) exclaimed at first glance, "My sister!––is it you? Alas! what mean these bifurcated habiliments?"This would be about the proper theatrical style; but truth in this instance compels us simply to say, the handsome quadroon turned out to be a female who had runaway from her master (a Mr. Graves) in Northwestern Missouri. Her name was Caroline Graves.

When the fugitives reach Chicago they are left to shift for themselves, and then commences thei[r] experience of the blessings they have run away to gain. It is a rather discouraging fact that the great majority of fugitives who arrive here find the road to an honest living one rather more difficult to travel than that which brought them from Missouri. The condition of many of them is wretched in the extreme, and they are forced by sheer hunger into the unlawful business of stealing chickens, which a great many of them pursue with energy. Doubtless a great many wish they were back again; yet knowing that to return would insure their shipment to a Southern slave market, they prefer the rigors and snows of Canada to a doom that, in their imagination, is fraught with more terrors than death.

"The African Excitement," St. Louis, MO Republican, April 9, 1861, quoting the Chicago Post