THE WESTERN FIELD.

RICHMOND, Wayne Co., Ind.,

October 11, 1853.

DEAR FRIEND QUINCY:

With your power of the pen, one could give some rather vivid sketches of 'Field-Hand' Anti-Slavery Experience, here in Indiana. Here is a fruitfulness of theme, exhaustless as the fertility of the prairies.

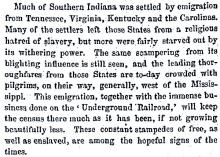

Much of Southern Indiana was settled by emigration from Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky and the Carolinas. Many of the settlers left those States from a religious hatred of slavery, but more were fairly starved out by its withering power. The same scampering from its blighting influence is still seen, and the leading thoroughfares from those States are to-day crowded with pilgrims, on their way, generally, west of the Mississippi. This emigration, together with the immense business done on the 'Underground Railroad,' will keep the census there much as it has been, if not growing beautifully less. These constant stampedes of free, as well as enslaved, are hopeful signs of the times.

I wish you could see some of this Western travel. It seems almost a pity that you pledged yourself to live so long, only for the good of new organization. But for that, you might venture one journey into these romantic regions--for such they are becoming; as it is, you had better not run the hazard.

But the modes of travelling, among these emigrants, are a curiosity. I saw a team, the other day, of three yoke of small, speckled steers, attached to a waggon which might have been in Noah's ark--or might not. The steers were six in number, only. Had they been seven, I should have taken them for the ghosts of the seven 'ill-favored and lean' cattle of Pharoah's dream. A stout, strapping girl of eighteen or twenty was driving, with a whip eight or ten feet long; the stock, I mean; the lash, a leather thong, was much shorter. This substitute for 'straw and provender' she held in both hands, running back and forth, and wielding it with a diligence which led me to fear that poverty, or some other sad cause, was compelling her to 'work her passage.' She was shod, though her cattle were not. In matter of stockings, however, they were all on an equality; while her scanty skirts, retrenched nearly to Bloomer height, favored her locomotion, and gave her a free and easy manner, not at all to be despised. A dozen passengers, with all their effects, filled up the inside.

One of our friends, who lived many years on a turnpike leading to Virginia, amused us greatly, one day last week, with stories of what he often used to witness among this class of people. He said he had seen as many as five or six families leaving Virginia in a company, all on foot, and barefooted, at that, (and all the younger ones bareheaded, too,) with all their goods and chattels in a little rickety go-cart, drawn by a single two years' old steer! He said that almost all the men carried a gun, and that there were nearly twice as many large dogs as men. Whiskey and tobacco made much in their bill of fare.

Another case was this. He said he met one day a young couple, evidently just setting out in life, well-looking people, both of them, and their mode of conveyance was by a yoke of oxen, without any cart or carriage whatever. On one of the oxen was bound a feather bed, carefully covered, with much loading of various kinds besides, and on the other rode the young bride, with baggage proportionate, and the husband, on foot, brought up the rear. And, said our friend, 'if slavery's contamination had not spoiled them, they are now probably rich and fine people, somewhere in the West.'

Slavery has 'spoiled' many of these new settlers. One can hardly have any idea of the difference betwixt them and a New England colony, as you find it so often in Northern Ohio and Michigan. It is seen in every department of life; in the roads and bridges, in the carts and carriages, in gates and fences, in the school-houses and meeting-houses, pews and pulpits, as well as in their laws and constitutions, their learning and religion. All over Indiana, as far as we have travelled, the turnpikes are good, but the tolls on some of them are enormous. The common roads are often only racks on which to torture carriages, or break the bones of passengers; and it is generally only the smallest streams that boast of bridges, and, six times out of seven, these are impassable, and you turn out and go through the channel. The large streams have generally no bridges; and when they are much swollen, travelling in very difficult. We had our baggage sadly wet, a day or two since, in crossing one, although now, the water every where is at its lowest ebb.

You ought to see us on one of these roads, making our way home from an anti-slavery meeting late at night; the sky muffled in angry black, and the moon just then on important business the other side of the globe. One night, I walked on before the carriages (an aged man and his family were with us) and bore a lantern. It was very dark, and we had three miles to go, twisting among stumps and gullies, and round broken-down bridges, or trees fallen across our track. It kept getting worse and worse, and I told my companions that it must be the road I had heard described by a traveller in these regions. He said it went out of town, in the morning, a broad, beautiful turnpike. Before noon, it had shrunk into a dismal cow-path; and at dark, he found it had pinched into a squirrel track, and took up a tree.

Another time, a man rode on horseback and carried a lantern. A part of the way, there was no road over cut through the woods. Once our guide got bewildered, and we came to a full stand. He soon, however, got his reckoning again, and led us safe to his hospitable home. The next night, we were conducted home through the woods by a tall Hoosier, good six foot without his stockings, bearing a brilliant torch in his brawny arm. I could not have carried it as he did five minutes; although I did one day, in your county of Norfolk, walk seven miles and a half in two and a half hours, with baggage that we weighed afterwards, and found it thirty pounds. I have never seen a more picturesque object than our guide presented. Straight and tall as an Indian chief, he dashed onward in the thick forest, a blaze of splendid light opening up the darkness for many rods around, and our snorting horses treading close upon him, evidently delighted and animated with the scene.

Last night, we could borrow no lantern, and no one on our route had any, into whose light we might fall. We begged a candle, as there was no wind, and a young man who was going with us, volunteered to guide our horses, with me on his horse before, and the lighted candle in the back part of the carriage, to be used in emergencies. A more beautiful beast I never rode, and she brought us safely a number of miles, fording two creeks, and much of the way in a thick forest, where the road to me was wholly invisible, and I rode literally by faith and not sight. We reached our home at a little before midnight.

Many of our meetings are held in log houses; sometimes in log school, sometimes in log meeting houses. Of the seats in these places, some Hoosier Cowper can yet write another 'Task'--though the day may be distant when he can commence, like his English prototype, with, 'I sing the Sofa.' But he may say with him, of the Lounges and Ottomans of to-day--

'-----------------------Four legs upholding firm

A messy slab, in fashion square or round.'

Such is the furniture in almost all these buildings; and the legs projecting through the slabs an inch or so, render them any thing but comfortable seats for church members and ministers, while we portray before them their pro-slavery sins and iniquities. But in most of the churches we have seen, these are all the seats they have. Nor is any partiality shown to the pulpit, or the 'high seat' in the Quaker meeting-houses.

Of the Education, Laws and Constitution of Indiana, I may say something at a future time. You will not understand me as speaking of all the people in this section, in what I have said. But where persons have come from the slave States, not one of my pictures is overdrawn; so deadly is the effect of the 'Peculiar Institution,' on all who fall under its contamination. Good folks they would be, but have never learned the way. Comfort and convenience, good taste and refined manners and habits, must be learned elsewhere, or be unknown and unthought of. And then, all such persons are the most deadly persecutors of the colored people, on account of their complexion, to be found in the world. The hatred of many of them towards a negro rises to a perfect passion. They would have been slaveholders, had they been able. As it is, they are, very many of them, ever ready to run down and return a fugitive slave.

A few years ago, two slave girls, nearly white, escaped from Tennessee, and took refuge in a colored settlement near where we held a meeting last week. On a Sunday morning, their pursuers arrived, and rallied the whole region to the rescue. Three times that day, our friend told us, he was summoned by a Justice of the Peace to go in pursuit. The colored settlement was besieged by nearly two hundred armed men, drunk with rage and whiskey, some with rifles and muskets, others with clubs and cutlasses. One old man, over sixty, and half doubled with rheumatism, was on the spot, with loaded rifle, and hungry for his prey as a hyena. A messenger galloped up to a Methodist meeting in the place, and with startling cry roused up the worshippers to the holy hunting. Nearly every man went, and the minister preached to the women, and prayed doubtless for success in the heavenly warfare to which their husbands and fathers had consecrated themselves. Once, the pursuers thought that his prayers and their bravery were to be crowned with divine success and blessing. The victims appeared in sight, and were hailed by their master. A shout of devilish delight rent the air. But they were all doomed to disappointment. Both the girls slipped on suits of men's apparel, and neither Tennessee nor its blood-thirsty hunters ever saw them more.

That County is now the best in the State. It is a part of the Congressional District of George W. Julian, and given a majority against the new Constitution, with its atrocious and unheard-of proscriptions and cruelties towards the people of color. The people are improving every way, and could our laborers be succeeded by enough more of the same sort, a revolution, a grand and glorious one, would soon ensue.

Pardon my great length, and believe me,

Ever, truly yours,

PARKER PILLSBURY.

"The Western Field," Boston (MA) Liberator, October 21, 1853, p. 3.