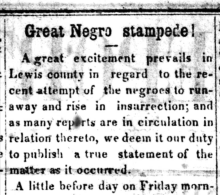

Great Negro stampede!

A great excitement prevails in Lewis county in regard to the recent attempt of the negroes to run-away and rise in insurrection; and as many reports are in circulation in relation thereto, we deem it our duty to publish a true statement of the matter as it occurred.

A little before day on Friday morning last, a negro man belonging to James Miller, came into the house ostensibly to make on a fire. Before going out, Mr. Miller heard him step towards the gun rack, take something, and leave with caution.––The circumstance exciting some suspicion, he went to the door and called first one and then another of his negroes, but receiving no answer, he went to the negro quarter and found no one there. He then aroused the family, first ascertaining, however, that both his guns were missing.––The neighbors were alarmed as soon as possible, and pursuit made. Mr. Harvy Henderson was the first to come in sight of them. In addition to the guns, they had taken Mr. Miller's wagon and team. Mr. Henderson approached near enough to identify the wagon, &c., and then quickly wheeled his horse to notify and bring up additional force. And it was well he done so; it was afterwards ascertained from some of the negroes that they had determined to kill him, and for that purpose, were bringing a loaded gun to bear upon him as he wheeled his horse and disappeared.

The pursuers, numbering about thirty guns soon came up. The negroes, amounting to between twenty and thirty, halted. They had three guns together with large clubs and butcher-knives. Besides Miller's negroes, some eighteen or twenty, there were several belonging to Judge Wm. Ellis, Mr. McKim, and Mr. McKutchen. As soon as they halted, they made their dispositions for an obstinate defence. Their pursuers marched towards them in regular order with presented guns.––When near enough, they asked them to surrender––they refused. They drew nearer and nearer, parlaying and insisting on a surrender––the negroes still manifesting the most dogged and settled hostility, peremptorily refusing to yield. Finally, after waiting and reasoning the case with them without the least apparent effect, and until all patience was exhausted, they commenced closing upon the negroes, when Miller's John, a very powerful negro, and fierce as a grisly bear, confronted Capt. J.H. Blair with his club raised in the act of striking, when Mr. Miller, his master, told Blair to shoot him. Blair made one step backwards and fired––the negro turned partly around, recovered, seized his knife, and was in the act of rushing on Blair, when John Fretwell fired at him, and he fell dead. Both shots took effect.

Undismayed by the occurrence, the other negroes still maintained the same hostile attitude. Five minutes were given them to consider of their surrender. The women first gave up, and implored the men to do so likewise, as John was already dead. Before the end of the time the men yielded; gave up their weapons, were bound and brought to Canton. The leaders have been shipped to St. Louis and sold.

It has since been ascertained that it was intended to be a general insurrection; and, to that end, it is believed that nearly all the slaves in the county had notice, and were to have met and rendezvoused on Friday at Canton. The plan was to kill all the negroes who would not join them––and with force of arms move off in a body to Illinois, and thence to Canada. However preposterous the plan may seem, it certainly has a good deal of truth for its foundation. The younger negroes not only disclosed it, but others, who did not join them, acknowledged they were notified and knew of it.––Besides, others have made a break. We understand that Parson James Lillard's negroes, in his absence, after abusing the family and making many wicked threats agains them, made off, but were luckily caught by the neighbors and lodged in the Monticello jail.

In our paper of Oct. 4th, under the head of 'Runaway Negroes,' we warned the people to keep a vigilant eye over their negroes. That they had made a start in Shelby County, and they might look out in Lewis and other counties. That while Missouri was united and firm in support of her constitutional rights against northern aggression, we had peace––the abolitionists were driven in terror from our borders and fled with alarm from amongst us. but, alas, at an evil hour, a powerful voice––a voice once trusted––sounded again the tocsin of alarm from the very centre––the very Capitol of the State! and from that moment, that united and determined opposition which once marked the councils and opinions of Missourians, constituting their strongest shield of protection, was dissolved––its moral force destroyed––its olive branch of peace withered and blasted.

When the leading man of our State for twenty-five years––trusted and revered with all the confidence that a noble and generous people could bestow, suddenly deserts his post––repudiates the cherished doctrines of his life, and strikes down the moral barries erected for our defence, what better coudl we expect? When such a man as Benton unites the influence of his name and fame with free soilism, and records his votes in the Senate with such notorious abolitionists as Hale and others to raise the African blood to social and political equality with us, can we expect safety to our property, or respect for our constitutional rights?––

When our Captains and Generals turn traitors, can we hope the enemy will not invade us, and dispoil our property? No sir! no! Such hopes would be delusive––would be vain and evanescent.

Will any one say that this is a mere fancy sketch? Let him turn his eyes to the north––what does he see? Instead of the vision Benton saw in 1830, and applied to Webster, he beholds a stearn reality in its stead––not Webster, but Benton himself figures as its chief. He beholds at the head of every free soil and abolition newspaper, the name of Thomas H. Benton for President in 1852––upon every abolition and free soil banner, that NAME is inscribed! He beholds an army with banners––with mottos––with inscriptions––their shirts red with the blood of murdered constitutions––with the grim carnage of fraternal massacre, moving on, hymning the praises of their chieftain to the next Presidency.

Democrats! how is this? How long has it been since Benton became the favorite candidate of free soilers––of abolitionists! Wake up from your lethargy! Examine your political chart, and see where you are. Can you––YOU––Democrats! fraternise with such as these––the Blood hounds who are hunting you to the death––and tearing the vitals of your dearest civil and political rights? No! never! never! You would scorn the association––you would shudder at the contagion of their blighting touch!

We don’t charge that his speech at Monticello was the immediate cause of the difficulty with our negroes. But we do charge that his speeches through the State and his agitation of the question have produced it all. We know, as an illustration, that many farmers and others were doing well, and felt perfectly satisfied with their condition, until the California gold agitation spread amongst us. Then they became dissatisfied with their condition––left family, friends and all, in the hope of doing better. Just so with the negroes. When Benton came to the State last spring, all was peace––the negro was happy and contented with his master. Benton made his Jefferson City speech––passed on, making daily speeches through the State––the agitation spreading wider and wider. The negro began to hope––became dissatisfied with his condition––began to plot to change it––and recent events are only some of the bitter fruits. His speech in Monticello but hatched the plot, which his agitation speeches elsewhere originated.––The negro’s ear is ever open, and his mind ever credulous to prospects of freedom; and whether present or not, he soon learns all that may be uttered on the subject.

Whether Tom Benton is an abolitionists, or not, they at least claim that he is engaged in their work in Missouri. Whether he intends it or not, the effects of their misdeeds follow him wherever he goes. Indeed, disguise it as you will, whether he intended it or not, his passage thro' the State has very materially disturbed the peace of the country, and rudely shaken the harmonious relations heretofore existing between master and servant.

"Great Negro stampede!," Canton (MO) North-East Reporter, November 8, 1849 (from microfilm at State Historical Society of Missouri)