By Matthew Pinsker

This 2021 essay offers a concise introduction to the subject of "slave stampedes" and their impact on the fight to destroy American slavery. It describes the origins of the term, provides a chronology for some major antebellum and wartime stampedes along the Missouri borderlands, and assesses how scholars, teachers and preservationists might use this information to help expand their interpretation of slavery resistance in order to include the concept of "mobile insurrections." The author presented an earlier version of this paper at the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) conference in October 2019. The revised piece now includes embedded multi-media and clickable endnotes that take readers directly to the primary and secondary sources which inform this work. For a printable version, please download this PDF.

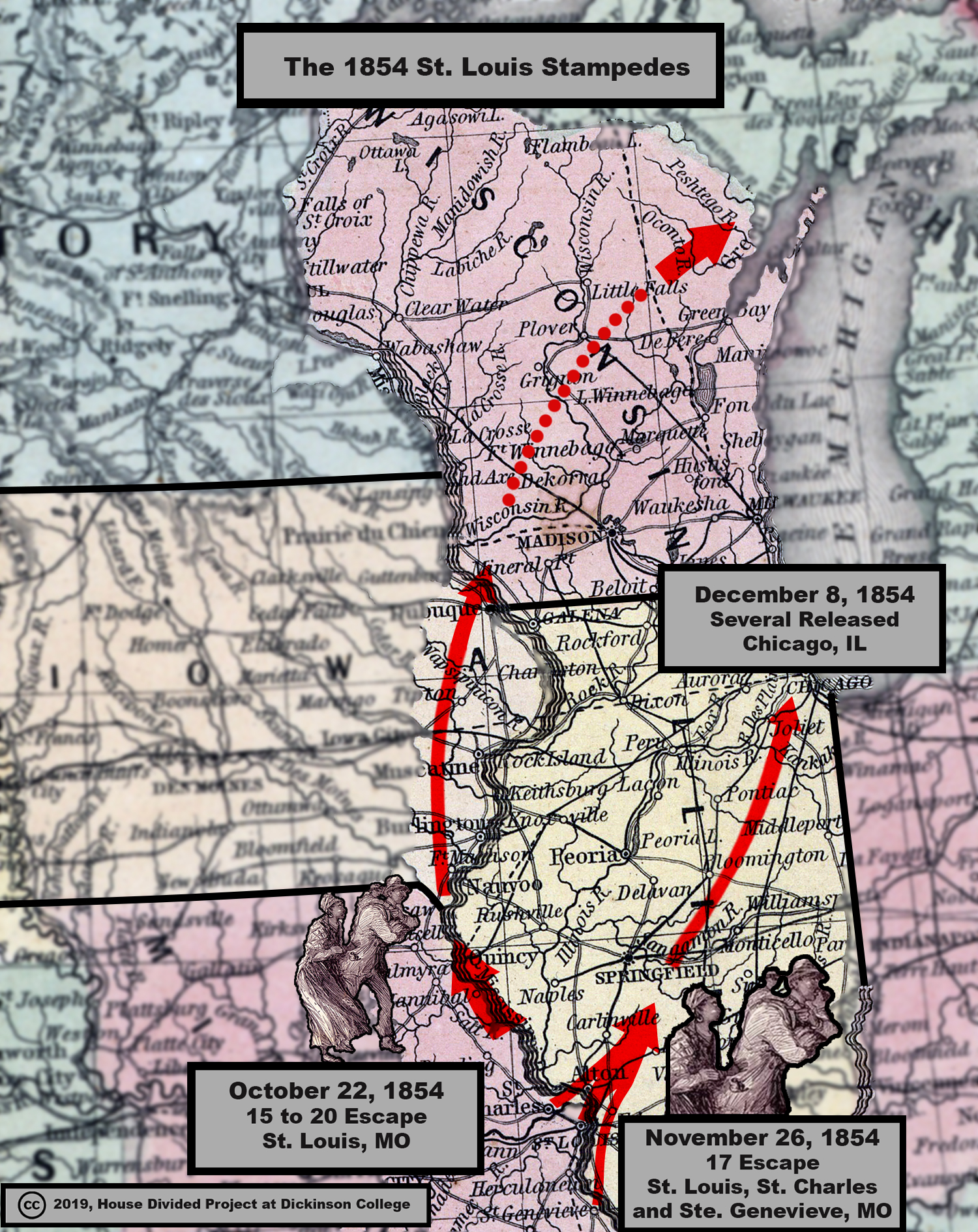

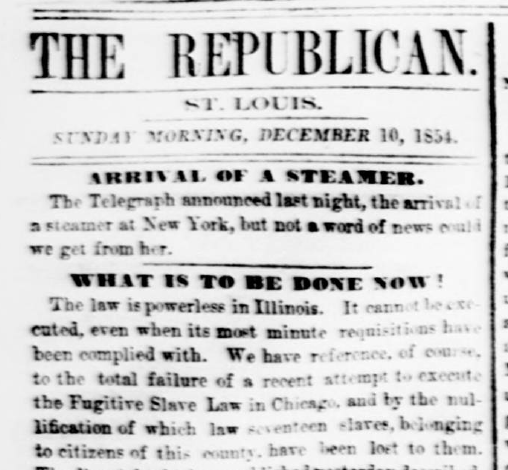

In December 1854, the St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican started complaining about the escalating number of runaway slaves who were escaping from their city. “Not a week passes by, without ten, fifteen or twenty slaves being run off by Abolitionists,” the conservative southern Whig journal fumed in an editorial entitled, “WHAT IS TO BE DONE NOW?” Sensing a vast antislavery conspiracy, the newspaper searched for answers: “These negroes have not left good homes without the aid and persuasion of white men, as well as free negroes, and a better police must be established.”[1] This apparent concern about enslaved people from around St. Louis getting enticed from “good homes” was essentially bipartisan in nature. Benjamin Gratz Brown, the editor of the city’s Missouri Democrat, offered similar complaints. His newspaper had been more focused that year on the upheaval over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, but throughout the previous several months, Gratz’s journal had also been reporting rather breathlessly on several audacious group escapes that had been roiling the area’s slaveholders, and which they were quick to blame on “the numerous underground railroad agents that infest our city.”[2] The Democrat was especially scandalized by the “fifteen or twenty slaves” who had departed together on a Sunday night in October, and that seventeen more who had fled in coordinated fashion from various locales near St. Louis, later in November. “STAMPEDE AMONG THE AFRICANS” and “ANOTHER SLAVE STAMPEDE,” were the reports from the anxious Democrat headlines.[3]

This was a hidden tipping point for the sectional crisis, one that most scholars and teachers have so far failed to recognize. What was happening around the Missouri borderlands in the latter half of 1854 was just as polarizing as other better known fugitive slave episodes from that year, such as the explosive Boston rendition case concerning Anthony Burns or the dramatic rescue of Joshua Glover in Milwaukee. It was also perhaps more important –at least over the long haul-- than the crisis that was brewing across the Missouri border in the Kansas and Nebraska territories. But unlike those now well-studied flashpoints, this festering 1854 crisis over “slave stampedes” in St. Louis has not attracted extensive analysis. Even that evocative metaphor --slave stampedes-- which journalists back then frequently used to describe what they perceived as an epidemic of group escapes across This was a hidden tipping point for the sectional crisis, one that most scholars and teachers have so far failed recognized.the Upper South, has become surprisingly obscure. Yet the story of “slave stampedes” is directly relevant –maybe even central-- to the coming of the Civil War. The revolutionary efforts of entire groups of freedom seekers, haunted the nightmares of antebellum slaveholders across Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Virginia, and beyond. In fact, the specter of slave stampedes loomed so largely in American political culture that events such as John Brown’s 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, Benjamin Butler’s “contraband of war” declaration in 1861, or even Abraham Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation in 1863, cannot be fully understood in context without some reference to “stampeding” slaves. It was a truly powerful metaphor that reflected an even more powerful desire –the revolutionary determination of some enslaved African Americans to have both freedom and family, even at the risk of significant violence.

Defining the Term

The very first edition of John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms published in New York in 1848 offered an entry for “stampede” or “stampado” that identified its origins as the Spanish word “estampado” which it defined as the “noise of stamping feet.” According to Bartlett’s, the American usage of stampede was supposed to describe the “general scamper of animals on the Western prairies, generally caused by a fright.” The editor then provided a few literary examples which came mostly from early nineteenth-century Western fiction or from various explorer’s accounts and depicted the panic of cattle and horses. However, when Bartlett revised his popular dictionary in 1859, he expanded the entry for stampede into nearly two full pages in order to illustrate how the term had been rather quickly “transferred to men” from “animals,” including in its applications as a metaphor for rambunctious young boys, matters of high-stakes finance, and even for freedom-seeking enslaved people. Quoting from the Baltimore Sun on April 9, 1858, the second edition of Bartlett’s featured a sample usage of “slave stampede” that ended with the phrase, “… there would seem to have been a considerable stampede of slaves from the border valley counties of Virginia during the late Easter holidays.”[4] By the start of the Civil War, it was this type of usage --referencing groups of escaping enslaved people-- that had become as popular as any other. The London Times observed in June 1861 that stampede was “a word which the Americans have borrowed from their prairies, and [have] applied most expressively to a general rush of negroes from slavery.”[5]

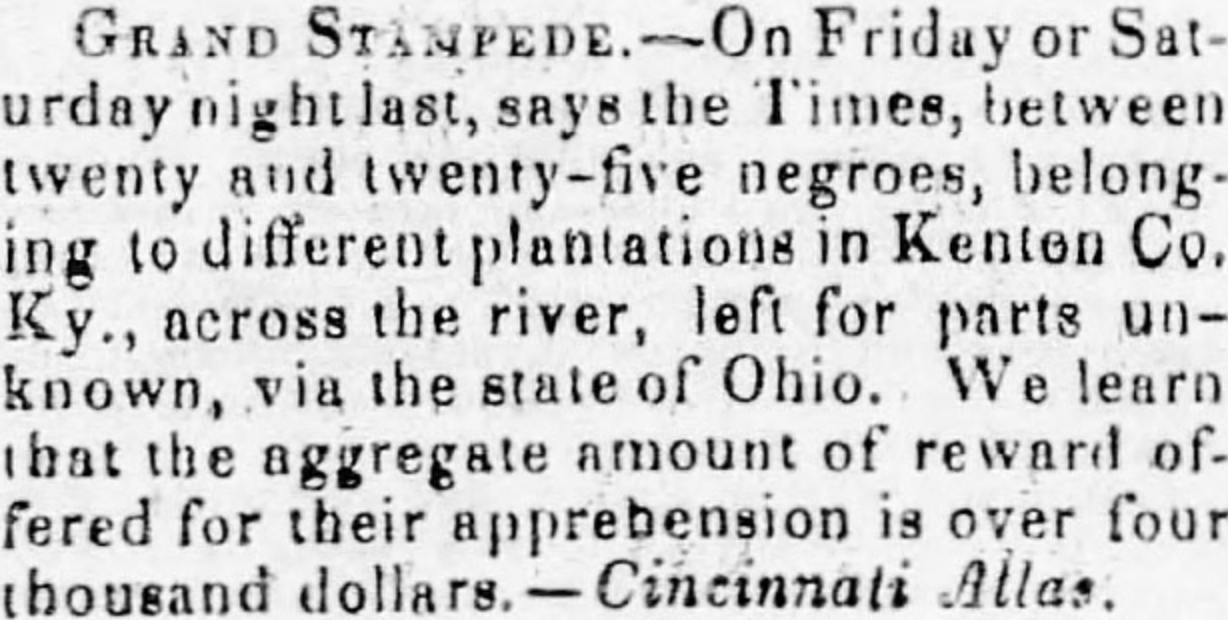

Examples of slave stampede terminology first started appearing across the national press in the late 1840s. The earliest references appear to date back to May 1847, when various newspapers in the country reported on at least two different mass escapes which had originated from northern Kentucky. The Cincinnati Atlas, a Whig newspaper, highlighted the flight of “between twenty and twenty-five negroes” from across the Ohio River by way of Kenton County, Kentucky, under the headline, “GRAND STAMPEDE.” The brief item noted that the runaways came from different

plantations heading “for parts unknown” and that the combined rewards for the freedom seekers was currently totaling over $4,000.[6] Just over a week later, a newspaper in Washington, DC reported that “a stampede of negro slaves” had recently occurred about seventy miles eastward along the Ohio river near Maysville, Kentucky. Those runaways, according to the Daily National Whig, were definitely headed to “the wilds of Ohio and Canada.”[7] That particular stampede from Maysville garnered a significant amount of national attention. A Massachusetts journal soon reprinted an excerpt from another paper which angrily blamed the “negro stampede” on the 1844 schism of the Methodist Church. According to the original article in the Covington (KY) Register, “five or six” of the Maysville escapees “belonged to a prominent and influential member of the Northern Methodist Church” who was apparently living in the southern city and had been hosting a visiting Northern Methodist dignitary. William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, then ran this same story in July without any additional commentary.[8]

The next year, 1848, there appeared over fifty references to “slave stampedes” or “negro stampedes” or some variant of those phrases in newspapers from more than twenty different states, though the majority of these reports concerned one massive attempted escape in August, the so-called “Doyle Conspiracy” in Kentucky. The coordinated flight of more than fifty armed slaves from the Lexington area, allegedly orchestrated by a shadowy Irish immigrant named Patrick Doyle, resulted in a violent shoot-out near the Ohio River, the recapture of nearly all of the freedom-seekers, and a sensational trial afterwards for Doyle (who received twenty years in the state penitentiary). That incident in late 1848 received extensive national press coverage, and seems to have cemented the appeal of the stampede metaphor for future headline writers in both pro- and anti-slavery newspapers. It also set the template for understanding the typical slave stampede as a form of revolutionary action –a form of mobile insurrection.[9]

Map 1 --The following map depicts newspaper coverage of the 1848 Lexington Stampede

Click inside the placemarks above to gain access to full text of the newspaper articles

The new metaphor was certainly on the minds of editors during the following year when they reported on a similar sounding-sounding conspiracy in Missouri near the banks of the Mississippi River. In early November 1849, somewhere between 35 and 50 enslaved freedom seekers from Canton, Missouri in Lewis County gathered one night, attempting to escape to Canada by way of Illinois. The group was armed, and allegedly talked about murdering their masters in revenge as well as the need for silencing any enslaved people who refused to join them. The plotters included black men, women and children from several local farms, led by an enslaved figure known as “Miller’s John” and an older black female conjurer named Lin. The runaways neither killed nor silenced anybody at first, but they did have stolen weapons and fought back as soon as they were cornered by the patrollers. However, the resistance collapsed once Miller’s John, their male leader, was killed. It remains unclear what happened to the rest. Some may well have escaped, but many were sold into the Deep South. There was no trial. The similarities to the Doyle stampede in Kentucky did not go unnoticed. “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” was how the Cleveland (OH) Plain Dealer described the incident, with a headline that was later repeated or rephrased in dozens of other newspapers.[10]

Map 2 --The following map depicts newspaper coverage of the 1849 Canton Stampede

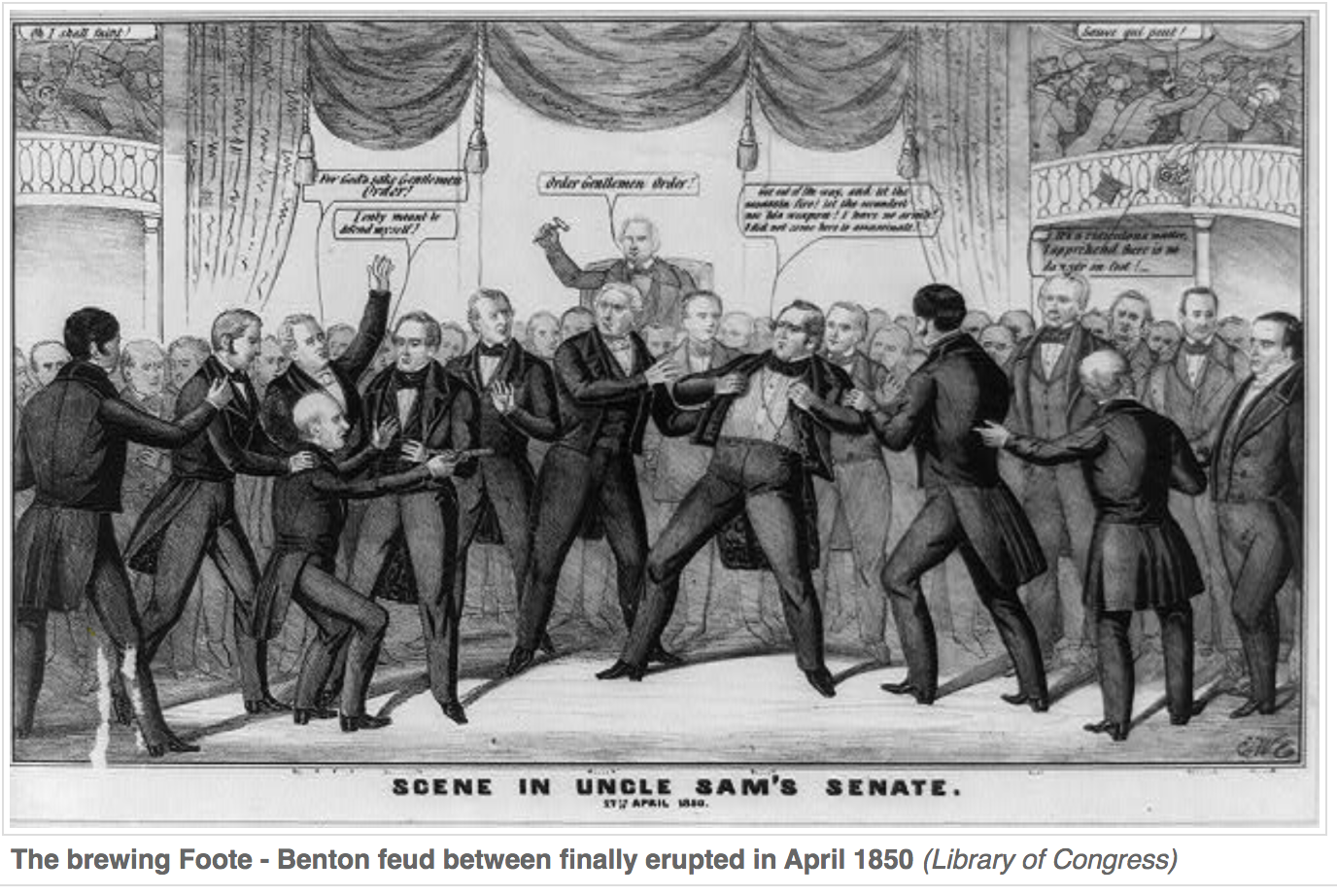

The episode also made it into the debates of the U.S. senate. In January 1850, just before the opening of the discussion about the Compromise of 1850, Henry S. Foote, an ardent pro-slavery southerner from Mississippi, denounced Missouri senator (and recent free soil convert) Thomas Hart Benton for allegedly encouraging “the slave population” of Missouri “in twenties and forties” to “put themselves in full flight for the Father of Waters.” Insulted, the independent-minded Benton stormed out in the middle of this fiery speech (from a fellow Democrat, no less), to which Foote responded with great sarcasm: “See, Mr. President, he flies as did those deluded sons of Africa among whom his eloquence is reported to have awakened a regular stampede.”[11]

Canton was one of the first --but definitely not the last— slave stampedes from antebellum Missouri. Within a couple of months after the shoot-out in Lewis County, there was a more successful stampede of an enslaved group from the St. Louis area that passed through Springfield, Illinois on their way toward Chicago. Jameson Jenkins, the free black teamster who helped them, was a neighbor and acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln.[12] Two years later, a failed stampede from Ste. Genevieve attracted widespread newspaper attention in the region. Historian Richard Blackett actually opens his chapter on Missouri and Illinois in The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018) with a description of the plight of eight male runaways who had fled from the Valle lead mines in Jefferson County and were eventually recaptured near Alton and Jerseyville, Illinois. Blackett, whose work on this topic represents the closest we currently have to a definitive study of the fugitive crisis of the 1850s, argues that this particular group escape “provides a window into the conflict over slavery” along the borderlands. The episode, combined with several others from Missouri during this period which he cites, seemed to prove to anxious pro-slavery forces what they considered to be the futility of the state and federal rendition systems in the Upper South. “While slaveholders did record some successes,” Blackett writes, with the failed 1852 Ste. Genevieve escape directly in his mind, “they could not totally stem the wave of ‘stampedes.’”[13]

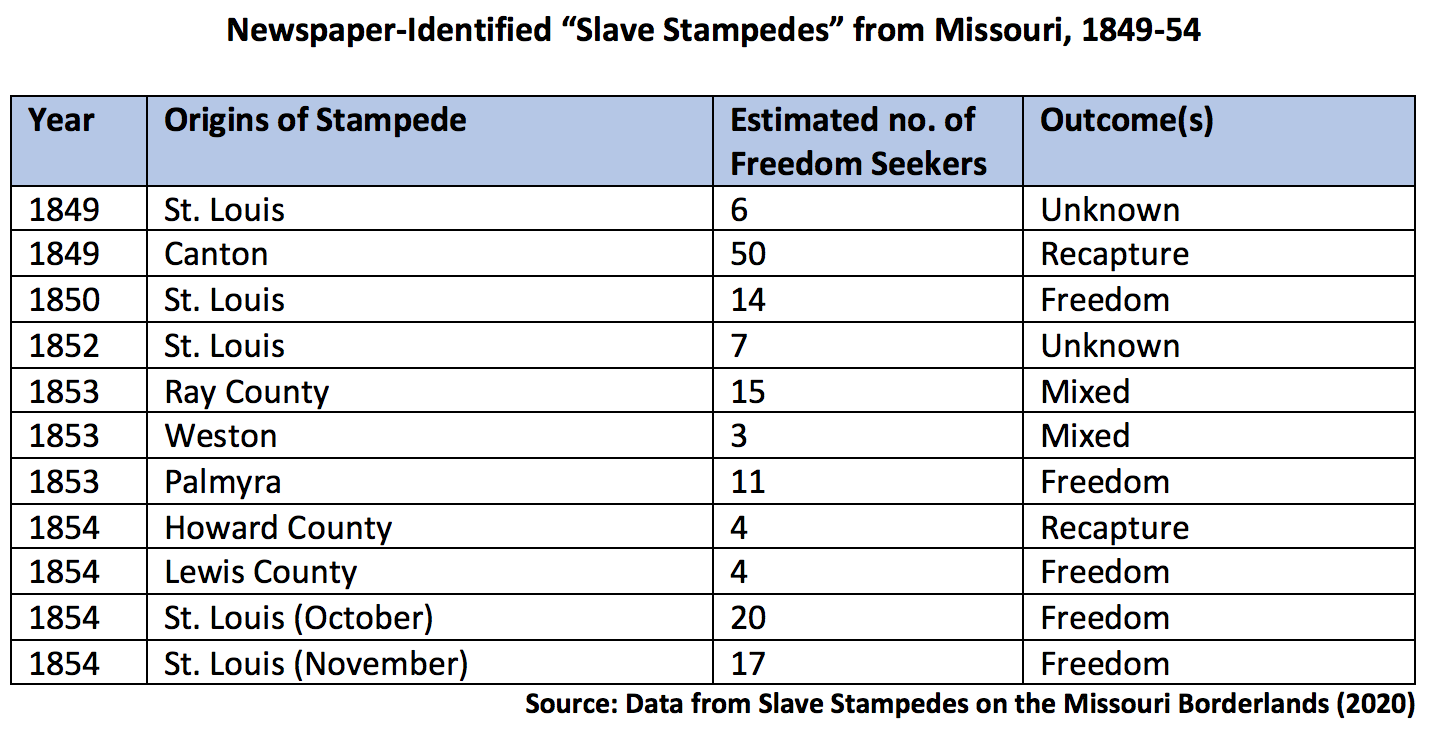

By the early 1850s, the popular metaphor for group freedom-seeking had become a headline fixture in the sectional propaganda wars. The Alton (IL) Telegraph, for instance, used a small feature on “Slave Stampedes” in 1853 to taunt its slaveholding neighbor across the river. “Slaves are running away from Missouri, at the present time, in battalions,” claimed the newspaper, adding, “It would be a glorious thing for Missouri if all her slaves should take it into their heads to run away.”[14] Here was a good example of how the metaphor was sometimes employed by opponents of slavery to elevate and valorize the freedom seekers. Still, journalists were inconsistent and imprecise with their “Slaves are running away from Missouri, at the present time, in battalions” terminology. For example, there was no fixed threshold in the mid-nineteenth century for what might have constituted the “battalions” of a typical slave stampede. Common newspaper usage almost always suggested that stampedes represented group escapes larger than a single family. Yet sometimes the phrase was also employed to describe serial escapes of smaller groups or individuals that appeared to be coordinated at some level. That was how, for example, an isolated trio of escapees from Weston, Missouri were touted in 1853 as their own “Negro Stampede.”[15] Nonetheless, some rough scale can be extrapolated from the various accounts. Out of twelve slave stampedes from the state of Missouri between 1849 and 1854, identified explicitly as such by contemporary newspapers, the average size of the escaping group was about 13 with a range spanning from three to the estimated fifty African Americans attempting (mostly unsuccessfully) to flee from Canton in 1849.[16]

The Power of Mobile Insurrections

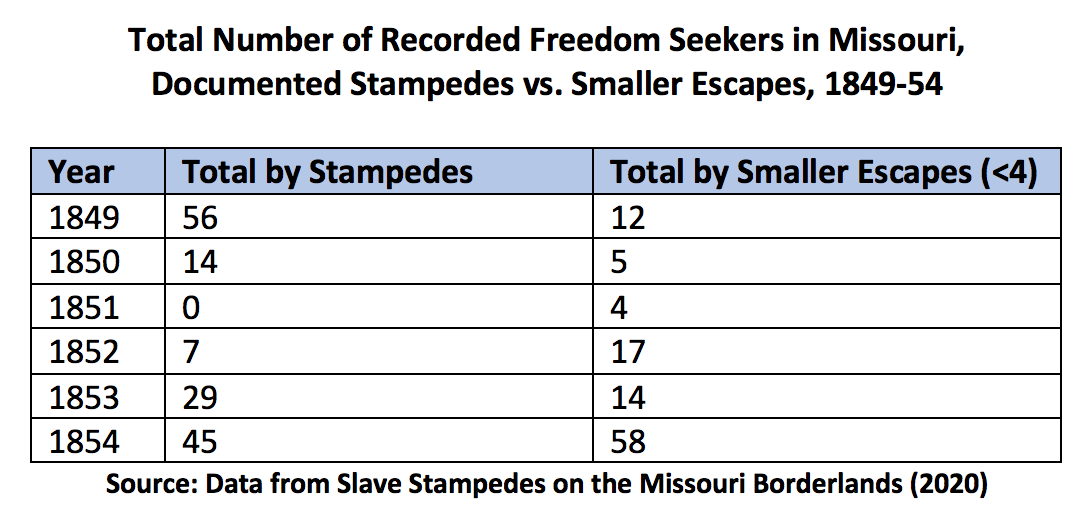

Slave stampedes were not just a rhetorical device employed by sensationalist headline writers. They represented a distinct form of African American revolutionary action, quite literally a mobile insurrection. Of course, it is difficult to determine their scale or even frequency with any kind of precision, but estimating total numbers of runaway slaves has always been something of a foolish scholar’s errand. There are only a few U.S. census reports on annual runaways to consider (such as Nonetheless, there were hundreds, even thousands of freedom seekers whose stories we can document with some detail. 1,011 uncaught escaped slaves listed in 1850; or only 803 reported at large in 1860) that are dubious in their reporting quality and not worth taking literally. One can also try extrapolating from various insurance claims, from some northern vigilance committee records, or from scattered plantation records. But ultimately, the pathway toward arriving at the consensus range of annual fugitives (about 1,000 to 5,000 permanent runaways per year) is mostly a guessing game. Nonetheless, there were hundreds, even thousands of freedom seekers whose stories we can document with some detail. In those case studies, we can usually make some reasonable assessments about average age, gender, occupational breakdowns, types of routes, and outcomes. Organizing the available data about slave stampedes also raises the possibility that we will sometime soon be able to determine whether enslaved people were more likely to attempt escaping on their own or by pairs, or through the agency of larger groups.

Scholars who have begun this work are finding some interesting insights. J. Blaine Hudson’s privately held fugitive slave database for Kentucky shows that “group escapes, or what slaveholders took to calling stampedes…increased substantially” in the Bluegrass state during the 1850s. Hudson’s records indicate that over one-third of all escapes in that region during the decade before the Civil War were stampedes.[17] But these statistics reflect numbers of escape cases, not total numbers of runaways. Based on our initial evaluation of the Missouri stampedes described in the regional newspapers, it seems quite possible that while group escapes were much fewer in number, they resulted in more total freedom-seekers than when individuals or pairs fled on their own. If true, this would compare to the familiar insight that while there were always more small slaveholders than plantation masters across the American South, more enslaved people actually lived on those larger antebellum plantations than on the combination of smaller southern farms and urban households.

Regardless of the exact numbers, however, it goes without saying that the slave stampedes from antebellum Missouri and elsewhere were uniquely revolutionary in nature. Anytime large groups of enslaved people moved together without permission, it was an act of extraordinary resistance. During the nineteenth-century (or almost any century), extended families or small village networks tended to migrate together. Yet this rather ordinary migration pattern always looked quite different whenever it was executed by runaway slaves. In one of the initial articles reporting on the 1854 St. Louis stampede, the Missouri Democrat opened its account about a “Stampede Among the Africans” with this sarcastic rendering of a communal departure: “On Sunday night last some fifteen or twenty slaves departed this city for the colder climates on our north.” The article went on to note that the fugitive migrants were likely part of the same church congregation and had preyed on their masters’ shared Christianity to help organize their flight. “They probably decamped about midnight,” noted the reporter, “having, permissions from their owners to attend church, gathered themselves together and set out in a company.” But the sheer normality of the group’s composition also seemed to make successful flight an impossibility. “It is extremely probable that all, or a majority of them, will be retaken, for with the gang are a number of women and children, and we believe also some aged and crippled.” [18]

Adding to the general incredulity about the escape, and offering a final devastating blow to southern honor, this “gang” of stampeding “Africans” was also fleeing from some of the most prominent slaveholding masters in the city. Pierre Chouteau, Jr., probably the wealthiest man in St. Louis at the time, owned a few of these runaways. Chouteau’s francophone family had built their great wealth on fur trading. He was also the father-in-law to John Sanford, busy at that time contesting the notorious Dred Scott case (on behalf of his widowed sister Irene Emerson) in federal courts. The other masters affected by the 1854 St. Louis stampede were powerful merchants and craftsmen. None of them expected to be humiliated in public by their own slaves. Almost the only way any white southerner could contemplate a successful escape for such an improbable group of fugitives was to raise the specter of outside white agitators. “If they are not very skillfully managed by their pilots,” observed the Democrat, “they will be baffled and brought back.”[19]

Yet these black families were not “baffled” at all and did succeed in finding liberation. We do not yet know their names or exact fates, but the local newspapers reported on the triumphant escape of the group within about two weeks. The migrants had made it across the Mississippi River to Illinoistown (East St. Louis), where they were then put on board a boat to Keokuk, Iowa “in boxes marked as goods.” “Arriving at Keokuk they proceeded across the country to Wisconsin,” reported the Democrat on November 1, 1854, “and are now very probably safe in Canada.” The correspondent thought he knew exactly where to place blame for the “stampede,” not with the frightened animals, as it were, but with the cowboys. “Doubtless the plan had been under deliberation for a long time,” he wrote, “the negroes acting by the advice and control of the numerous underground railroad agents that infest our city.”

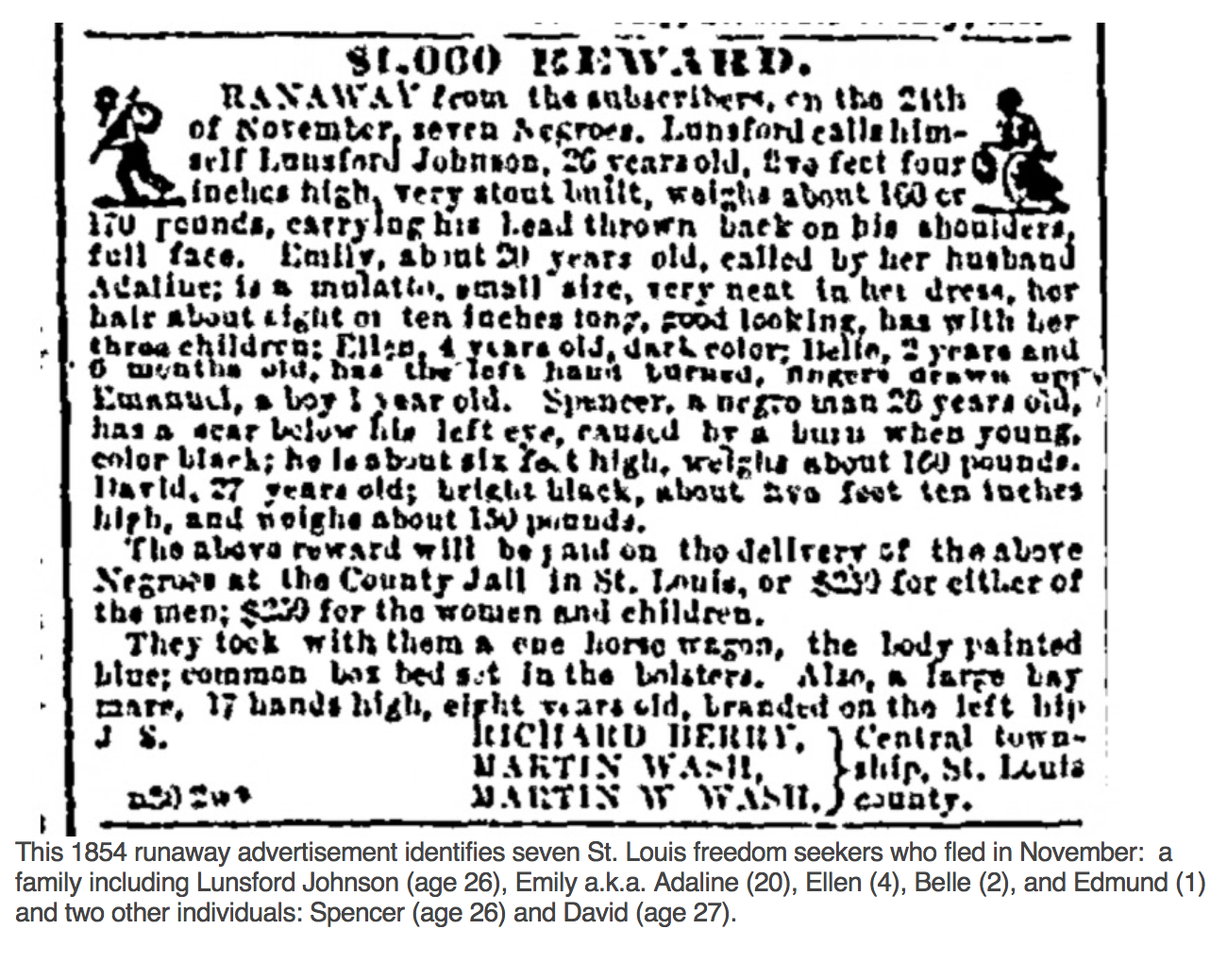

The obvious bitterness of that last line, made even more revealing since it was emanating from a free soil Democratic newspaper, provides the essential context for the explosion of concern that erupted when yet another stampede of slaves was reported in the area by the end of that same month. “ANOTHER SLAVE STAMPEDE,” announced the Democrat on November 30, 1854, detailing the apparently coordinated escapes of seventeen total freedom seekers, including ten enslaved people from St. Louis, four from St. Charles and three from Ste. Genevieve. This time the outcome of the attempt was mixed (some were recaptured), but even so, the result coming so soon after the other stampede proved even more frustrating for the slaveholders. The saga itself was quite revealing. The Chicago Tribune reported on December 5 that, “Last evening seventeen passengers arrived in our city by the underground railroad, and were immediately forwarded to ‘the land of the free,’ where they doubtless have arrived before this notice is generally read by the people of this city.”[20] But then it became apparent that the item placed in the Tribune was actually designed as a strategic misdirection. The enslaved, or at least some of them, were still planning to remain in Chicago.

Richard Berry, one of the slaveholders from St. Louis, had suspected this all along and had rushed up to Chicago seeking to recapture his human property. Berry easily secured a warrant from the new U.S. Commissioner in Chicago, John A. Bross, but he found it extremely difficult to have the rendition process actually enforced in a free state. First, the deputy marshal refused to arrest one of the fugitives identified by Berry, “fearful of his life if he attempted the task alone.” But then the cautious marshal also found it nearly impossible to find any local citizens to aid him –despite the provisions of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law requiring their assistance. Eventually, a local militia company did assist and some of the Missouri runaways were rounded up and brought before Commissioner Bross, but the federal official ended up releasing them “for want of sufficient evidence.”[21] The whole episode played out against a backdrop of angry protests from antislavery forces in the city, many of whom massed outside of the rendition hearing. The New York Herald took sharp note of the situation, claiming bluntly that Bross had been “Intimidated by the crowd of people.”[22]

The combination of all of these events is what set off the howls of protest from the St. Louis Missouri Republican. “WHAT IS TO BE DONE NOW?” the newspaper asked angrily in its editorial headline from December 30, 1854, and noting sadly in its lead sentence that, “The law is powerless in Illinois.” The column then bitterly summarized the facts of the recent stampede cases, denounced what it called the “nullification” of the Fugitive Slave Law and then compared what was happening with Missouri runaways to the Anthony Burns fugitive rendition which had played out in Abolitionist hot-bed of Boston back in May. “In Boston, when the slave Burns was arrested, the law was executed,” the newspaper recalled, “although a mob of white men and negroes attempted to prevent it, and in so doing murdered an officer in the performance of his duty.” The Republican did not also try to invoke the recent violence and legal battles which had erupted in Milwaukee over the runaway Joshua Glover (originally from Missouri), but it did reiterate yet again that “in Chicago the law is powerless.”[23] That was how it felt to them after nearly forty St. Louis-area African Americans successfully escaped from enslavement over the span of less than a month in late 1854.

The combination of all of these events is what set off the howls of protest from the St. Louis Missouri Republican. “WHAT IS TO BE DONE NOW?” the newspaper asked angrily in its editorial headline from December 30, 1854, and noting sadly in its lead sentence that, “The law is powerless in Illinois.” The column then bitterly summarized the facts of the recent stampede cases, denounced what it called the “nullification” of the Fugitive Slave Law and then compared what was happening with Missouri runaways to the Anthony Burns fugitive rendition which had played out in Abolitionist hot-bed of Boston back in May. “In Boston, when the slave Burns was arrested, the law was executed,” the newspaper recalled, “although a mob of white men and negroes attempted to prevent it, and in so doing murdered an officer in the performance of his duty.” The Republican did not also try to invoke the recent violence and legal battles which had erupted in Milwaukee over the runaway Joshua Glover (originally from Missouri), but it did reiterate yet again that “in Chicago the law is powerless.”[23] That was how it felt to them after nearly forty St. Louis-area African Americans successfully escaped from enslavement over the span of less than a month in late 1854.

This was certainly not a final turning point in the sectional crisis, but it is perhaps best understood as a critical tipping point in Southern (especially Upper Southern) perceptions about the antebellum fugitive crisis. Nothing was the same after 1854. Anthony Burns had been returned to Virginia under an immense show of federal force in May 1854, but his rendition was the last official return of any fugitive slave from the New England states before the Civil War. Burns himself was also manumitted the next year through funds raised by black churches. Joshua Glover’s dramatic rescue by abolitionists in March 1854 had led to a series of confrontations between the Wisconsin Supreme Need some additional background on fugitive slave laws? Check out this post at our project blog Court (which wanted his rescuers released) and federal authorities, who were determined to send a political message about the law’s enforcement. That legal confrontation (which finally ended in 1859 with a Supreme Court ruling in Ableman v. Booth) was nothing less than a battle royale over nullification –in this case, northern nullification of the federal fugitive slave code. The real angst emanating from the St. Louis newspapers over the successful 1854 stampedes was only further evidence of how deeply pessimistic Border State slaveholders were becoming by the middle of the decade. They were convinced that the fugitive slave law had become a dead letter and that the prospect of keeping their enslaved property from running away was growing ever more dismal.

Revising the Narrative

Until recently, scholars have not focused much attention on the stampede phenomenon or the subsequent shift in white attitudes, especially as it seems to have unfolded in Missouri. Wilbur Siebert, who pioneered the academic study of the Underground Railroad in the 1890s, made no mention of antebellum slave stampedes except to credit the anxieties of Border State slaveholders with keeping them generally loyal to the Union during the secession crisis. “The prospect of a stampede of slaves, in case they should join the secession movement, was a consideration that may be supposed to have had some weight in fixing the decision of border slave states,” he wrote, adding, “Certainly it was one to which Northern men attached considerable importance at the time in

explaining the steadfast position of these states.”[24] In his groundbreaking work of Underground Railroad revisionism in the 1960s, The Liberty Line, Larry Gara did make explicit reference to the 1854 complaints of St. Louis newspapers, but he found in them only confirmation for his argument that the Underground Railroad as Siebert and others had envisioned it was mostly mythical. Noting that at least one St. Louis newspaper had appeared “skeptical” in the fall of 1854 about the claims of widespread covert white abolitionist assistance, Gara wrote that the over-heated charges, especially from the Missouri Republican, “proved nothing, but helped to give plausibility to the mass of stories which were eventually to form part of a favorite American legend.”[25]

Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018) delivers more nuance –and far more detail-- than Gara’s influential study, especially as it concerns the significance of group escapes along the Missouri borderlands. Blackett pointedly depicts the 1854 newspaper sensationalism in St. Louis as a byproduct of “an upsurge of stampedes from the city” and summarizes most of the key details regarding notable group escapes from the period. Later in the book, Blackett also observes in a different context that it was always “the frequency and apparent coordination of group escapes that caused the most concern” among slaveholders.[26] But even with these powerful insights, there is still more work to done in understanding the revolutionary dynamic embodied by the story of slave stampedes.

Four years after the “upsurge of stampedes” from St. Louis, for instance, there was an even more dramatic outbreak of group escapes across the state in Western Missouri. In December 1858, eleven enslaved people escaped from farms in Vernon County, assisted by Kansas abolitionist raiders under the direction of John Brown. One slaveholder was killed in this operation, but the group (which eventually became a dozen after one woman gave birth) made it over a thousand miles to freedom in Canada by March 1859. It was perhaps Brown’s greatest victory in the war against slavery and one which he himself apparently later described to witnesses as a slave stampede. During the congressional hearings about Harpers Ferry in early 1860, one of the Virginia prosecutors who had interviewed Brown following his capture in October 1859 testified that the abolitionist warrior had told him both operations (the 1858 Daniels raid in Missouri and the 1859 Harpers Ferry raid) were attempted slave stampedes. “He stated in substance,” recalled Andrew Hunter, “that his purpose in coming to Virginia was simply to stampede slaves, not to shed blood; that he had stampeded twelve slaves from Missouri without snapping a gun, and that he expected to do the same thing in Virginia, but only on a larger scale.”[27]

Nor was Brown alone in lending sometimes-violent aid to group escapes along Missouri’s western border. Just a few weeks after the Daniels raid in Vernon County, Dr. John Doy was captured in late January 1859 attempting to lead yet another group of eleven Missouri freedom seekers from Lawrence, Kansas into Iowa. Doy was a fellow abolitionist and had been an ally of Brown’s since the beginnings of the struggles of “Bleeding Kansas.” In fact, Doy (who was shortly liberated from Missouri prison in a shocking rescue) later blamed his group’s initial failure on Brown’s decision to keep all of the available abolitionist military escort for the Daniels party.[28] Reporting on both of these startling episodes shortly after they had happened, the St. Louis News had no doubt about how to characterize them. “We know from information received from private sources, that the slaveholders on the border are beginning to suffer severely from the constantly occurring stampede of slaves. They are enticed in gangs of dozens and scores, by sympathizers, into Kansas, kept concealed in the territory for a time, and then sent towards Canada, through Iowa.”[29]

Many American newspapers were also quick to characterize Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid in October 1859 as a potential slave stampede. They seemed to vacillate at first over whether to characterize it as a full-fledged “insurrection,” “riot,” “stampede” or as some combination of all of them. “It is supposed that the men in the armory are accomplices with the rioters,” reported the Baltimore Sun under an October 17th dateline, adding “As reports from Alexandria state that there has been a sudden escapade of slaves from that region, the belief exists that attempts to arrest a general stampede of slaves from Harpers Ferry has led to collisions as reported.”[30] Although labeling the attack as a “Servile Insurrection,” in its headline, the Washington Evening Star on October 20th, noted within its main report following Brown’s capture that even though the whole operation appeared to them as a “palpable absurdity,” there was also “no doubt an immense stampede was calculated upon by these fanatics.”[31] Over forty different newspaper articles appeared across the national press between October 17 and November 1, 1859 about Brown’s raid that directly invoked the concept of the slave stampede.

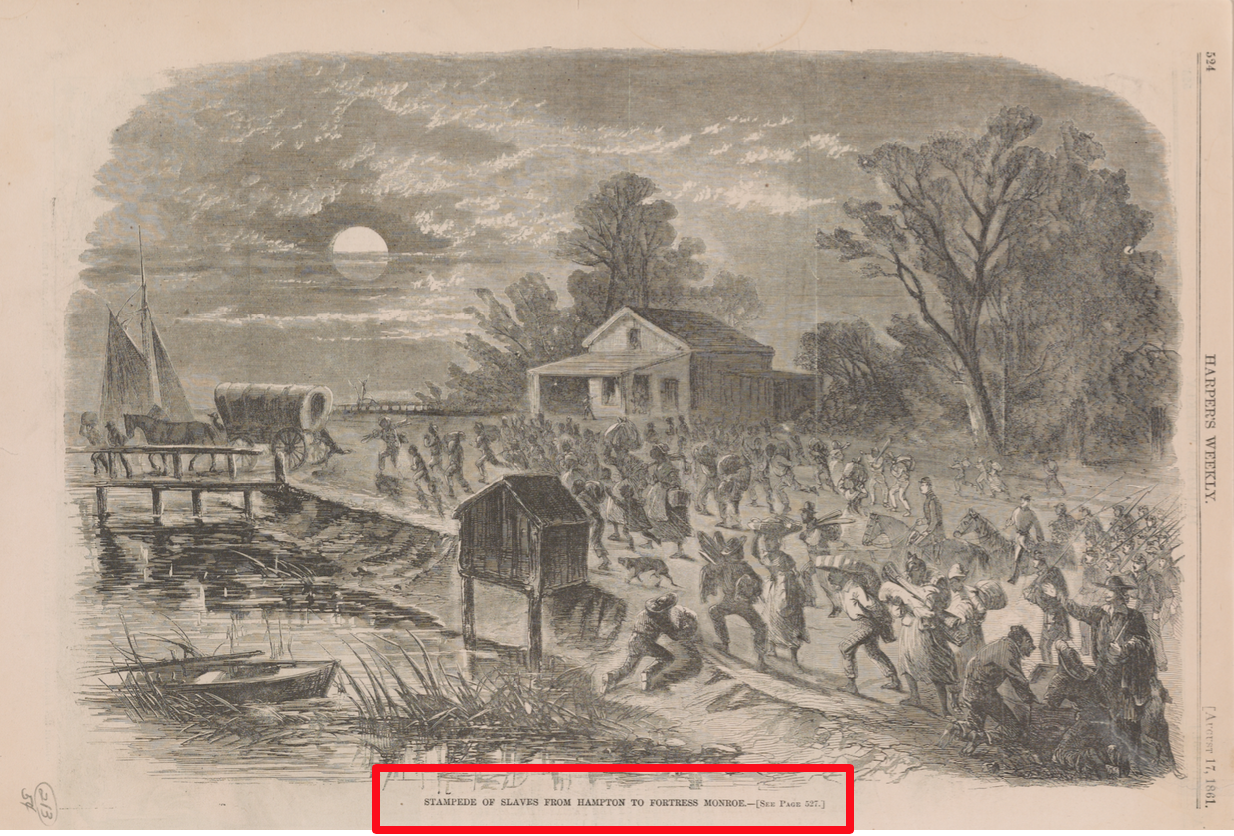

The stampede terminology also dominated newspaper coverage during periods of the Civil War. For example, the flight of contraband slaves in the spring and summer of 1861, outside of places such as Union-held Fort Monroe on the Virginia peninsula, generated dozens of stampede headlines. When the first Confederate officer confronted Union General Benjamin Butler demanding the return of three runaway slaves, the former Democratic politician from Massachusetts easily determined that he would not attempt to honor the Fugitive Slave Law. Eventually, after the War Department endorsed the idea that such enslaved people could be treated as “contraband of war,” hundreds of black Virginians began showing up behind Union lines. Yet even before most of the Northern press dubbed such runaways as “contrabands,” they were celebrating this spate of escapes as “stampedes.” Reporting on the “Fugitive Slave Question,” on May 30, 1861, the New York Herald commented, “It appears by advices from Fortress Monroe, that there is likely to be a stampede of the ‘peculiar institution’ through Virginia.”[32] Though noting the influx of runaways since Butler’s initial decision and the debate within the cabinet over how to proceed, there was no reference to contrabands until the next day. But even after the Herald had christened the “contrabands” on May 31, many newspapers continued to refer to the escaping fugitives as being part of a stampede.[33] On June 8, 1861, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper featured a two-page spread of pen sketches under the central caption: “Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia - their arrival at Fortress Monroe.”[34] Harper’s Weekly offered an even more artistic impression of a mass escape with various local black families on foot and in wagons fleeing toward Butler’s command in its August 17, 1861 issue, using the same type of caption, “Stampede of Slaves from Hampton to Fortress Monroe.”[35] Neither magazine used the “contraband of war” language in their captions. Today, most scholars and teachers rely on the Fort Monroe episode to help introduce the concept of wartime contrabands, but rarely if ever do they describe these escapes as stampedes.

Yet perhaps nothing better illustrates the contemporary ubiquity of the stampede metaphor than its private application by President Abraham Lincoln in early 1863 as he was defending his emancipation policy. The stampedes of enslaved people on the Virginia peninsula and elsewhere in the initial months of the Civil War had provoked Congress to adopt confiscation policies that were designed to authorize (or perhaps push) the president into emancipating slaves –initially those directly employed by the Confederate army (First Confiscation Act of August 6, 1861) and then any enslaved people owned by any rebel anywhere (Second Confiscation Act of July 17, 1861). Neither of these statutes actually used stampede or contraband terminology, but the second effort, adopted over a threatened presidential veto in 1862, was explicitly a liberation measure aimed especially at human beings, not merely property, specifically designed the enslaved as people being held as “captives of war” in the defiant language of the Republican-controlled Congress. Lincoln then drafted his emancipation proclamation in response to this Second Confiscation Act, but not at all reluctantly. In fact, Lincoln’s bold wartime liberation measure exceeded the statutory vision of the Congress by extending emancipation to any enslaved people held by any master (whether treasonous or loyal) in the Southern combat areas (including some places held by Union forces, like the Sea Islands of South Carolina).[36]

Once Lincoln announced this policy, in September 1862, the result was a new phase in the Union war effort. Emancipation did not become an official war aim with the issuance of the official proclamation, but after January 1, 1863 the liberation policy was most decidedly embraced as an essential war tool, designed to destroy the rebellion by freeing (forever) its coerced labor. Lincoln was known as a moderate, but he was clearly being quite radical in his determination to extend and make real this human rights measure. The best way to discern his publicly muted radicalism is to study Lincoln’s behavior behind the scenes. Just over a week after signing the proclamation, for example, on Friday evening at the White House, January 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln held a private meeting with two key Republican senators –John P. Hale of New Hampshire and Orville H. Browning of Illinois—where he boasted proudly about the reaction of Missouri’s enslaved population to the unveiling of the new emancipation policy. While pointing at a map of the western borderland area, featuring Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, the president claimed that since the first public announcement of emancipation in September, “the negroes were stampeding in Missouri,” and had been creating a backlash among Democrats in that region. Lincoln was trying to convince the senators to use this moment to press for a compensated abolition measure in Missouri, describing this Western slave state, according to the revealing but little-known entry in Browning’s diary, as “an empire of herself,” claiming it would be more than “enough” for the legacy of each of these three men, “if we make Missouri free.”[37] The revolution which had begun among enslaved black families in places like St. Louis and Canton had finally made it to the White House.

Whether Lincoln had actually used a version of the slave stampede metaphor, or if Browning had just thought he heard him do so, the point is the same. Stampeding slaves was a concept quite familiar to antebellum and wartime Americans. The term reflected a revolutionary phenomenon that had transfixed both slaveholders and abolitionists for nearly two decades. Each side in the sectional propaganda war was quick to employ the phrase or its variants in their headlines and newspaper columns. In the end, when assessing significance, that rhetorical choice matters as much as anything. Some 21st-century Americans might bristle at language that appears to equate freedom seekers with horses or cattle. They might worry that the term was universally employed as yet another way to dehumanize African Americans. Yet that is not the whole story. The term conveyed great power. For slaveholders and their allies, they undoubtedly saw that power through a white supremacist lens and used the language with disdain. Yet for the abolitionists and the freedom seekers themselves, the concept offered a quite different meaning. They saw it as validation of a powerful liberation movement.

How powerful this movement may have actually been is difficult to measure. There were dozens of antebellum slave stampedes and dozens more during wartime prior to the abolition of slavery. Many were successful, some entirely so. But the key statistic was never really about the number of actual runaways or successful stampedes, but rather the combined total of newspaper stories they generated. In that regard, stampedes proved to be a vital part of American political culture. The current research project undertaken by the National Park Service and the House Divided Project at Dickinson College has identified over one thousand articles (and counting) from across the United States between 1847 and 1865 using stampede or a variant to describe some type of freedom-seeking escape. These newspaper accounts document nearly 200 distinct stampedes from across the country, mainly in Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia and Maryland. The full meaning of those episodes --some now quite forgotten-- has yet to be systematically interpreted, but this project hopes at least to fully launch this long overdue academic and pedagogical conversation.

Conclusion

By 1860, Pierre Chouteau, the scion of St. Louis’s wealthiest fur-trading family, had seen his slaveholding property reduced to just five people (down from 15 in the early 1850s). Yet Chouteau, who had lost three of his enslaved servants in the stampedes of 1854, only conceded to the census taker on the eve of the Civil War that his household had one permanent “fugitive from the state.”[38] If nothing else, this is a good example of how dubious the census records are as sources for documenting escapes. But if Chouteau was consciously trying to downplay the meaning of his experience with escaping slaves, then Abraham Lincoln was not. Three years later, President Lincoln was privately urging on abolition in Missouri, confident that “stampeding” slaves were helping to prepare the necessary political ground work for his antislavery operatives. That is at least partly why just two years after those comments, Chouteau and all of the state’s “masters” forever lost their Somewhere between the breaking of tools and servile insurrections, there should be a category for slave stampedes in scholarly studies of resistance to enslavement.human property. No single factor can explain the destruction of American slavery, but slave stampedes were a distinct and significant part of that story. Cheryl LaRoche has written eloquently about the “geography of resistance” in order to explain the importance of recovering the roles of free black communities in the networks that supported runaway slaves.[39] This work on slave stampedes by the teams of researchers at NPS and Dickinson College suggests there should also be greater consideration for the “terminology of resistance.” Somewhere between the breaking of tools and servile insurrections, there should be a category for slave stampedes in scholarly studies of resistance to enslavement. These frequent group escapes on the antebellum borderlands had a tremendous cumulative impact. They were truly mobile insurrections. Seen in this light, a historical term like “slave stampedes” fits right alongside the more celebrated “Underground Railroad.” Both were metaphors born out of key transformations in the nineteenth-century American economy --railroads and westward expansion. Each term came of age almost simultaneously in the 1840s and both deserve to be analyzed and taught together.

[1] “What Is To Be Done Now?,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854.

[2] “The Fugitive Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 1, 1854.

[3] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854 and “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854. For more information on this particular episode, see Cooper Wingert, “1854 St. Louis Stampedes,” Project Blog, Slave Stampedes on the Missouri Borderlands (NPS / House Divided), 2019.

[4] John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States (New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1848), 330-1. John Russel Bartlett, Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States (2d edition; Boston: Little Brown, 1859), 444-5. Modern Spanish language dictionaries now typically define “estampado” as print or printed, not as a “stamping of feet.”

[5] London Times, June 19, 1861, quoted in “English Speculation on the War and its Issue,” New York Herald, July 2, 1861.

[6] Cincinnati Atlas reprinted in “Grand Stampede,” Danville (VT) North Star, May 17, 1847. Also reprinted in slightly edited form under the same headline in Prairieville (WI) American Freeman, June 9, 1847.

[7] Washington, DC Daily National Whig, May 26, 1847.

[8] Covington (KY) Register reprinted in “Negro Stampede,” Worcester (MA) Bay State Farmer and Mechanics Ledger, May 29, 1847. “Negro Stampede,” Boston (MA) The Liberator, July 16, 1847.

[9] Before Doyle’s August 1848 arrest in Kentucky, other mass escapes received a variety of labels besides “stampedes.” Two earlier mass escapes which failed in 1848, --the capture of 77 people on board The Pearl outside of Washington in April and the confrontation in Salem, Iowa in June that resulted in the return of most of the 16 people who had escaped from the Daggs farm-- were instead described in the press as “elopements,” “abductions” or even simply as, “negro stealing.” See, for example, “The Washington Slave Elopement,” Raleigh (NC) Register, April 26, 1848; “The Slave Abduction Excitement,” New York Herald quoted in Boston (MA) The Liberator, May 19, 1848; and “Negro Stealing,” New York Evening Post, June 21, 1848.

[10] “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” Cleveland, OH Plain Dealer, November 6, 1849. See also “Slave Stampede and Resistance –Their Leader Killed,” Baltimore Sun, November 7, 1849. “Stampede Near St. Louis,” Plaquemine (LA) Southern Sentinel, November 14, 1849. “Slave Stampede,” Fayetteville, NC North Carolinian, November 17, 1849. “The Great Slave Stampede in Missouri,” (Philadelphia) North American and US Gazette, November 22, 1849; and “Another Chapter of Southern Atrocities and Horrors,” The Liberator, January 18, 1850. For more details on this now-forgotten resistance episode, see older accounts by W. K. Moore, “An Abortive Slave Uprising,” Missouri Historical Review 52 (January 1958): 123-26 and George R. Lee, “Slavery and Emancipation in Lewis County, Missouri,” Missouri Historical Review 65 (April 1971): 294-317. Diane Mutti Burke has also put the episode into more sophisticated context in her more recent scholarship; On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 186. For more information on this episode, see Rick Beard, “1849 Canton Stampede,” Project Blog, Slave Stampedes on the Missouri Borderlands (NPS / House Divided), 2019.

[11] Henry S. Foote, U.S. Senate, January 16, 1850 quoted in Washington DC National Intelligencer, January 19, 1850.

[12] Illinois State Journal, January 22 and January 23, 1850.

[13] R.J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 137-40.

[14] Alton (IL) Telegraph, quoted in The Liberator, June 10, 1853.

[15] “Negro Stampede,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, June 24, 1853.

[16] This data is tentative but derives from the ongoing “Slave Stampedes on the Missouri Borderlands” project, 2018-2022 cooperative agreement between the NPS and the House Divided Project at Dickinson College. The twelve stampedes referenced here include St. Louis (6 people) in 1849, the Canton resistance (up to 50 people) in 1849, St. Louis through Springfield, IL (14 people) in 1850, St. Louis (7 people) in 1852, St. Genevieve (8 people) in 1852, Western Missouri (18 people) in 1853 (but that includes 15 people from Ray County and then another 3 from Weston), Palmyra (probably 11 people) in 1853, Howard County (4 people) in 1854, Lewis County (4 people) in 1854, St. Louis (20 people) in October 1854, St. Louis and other areas (17 people) in November 1854. This list of twelve slave stampedes from Missouri between 1849 and 1854 excludes group escapes not identified in the press as “stampedes.”

[17] Quoted in Blackett, 50.

[18] “Stampede Among the Africans,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854.

[19] St. Louis Missouri Democrat, October 24, 1854.

[20] Quoted in “News from the Fugitive Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, December 8, 1854.

[21] “The Constitution and Law Nullified in Chicago,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 9, 1854. See also Richard Cahan, A Court that Shaped America: Chicago’s Federal District Court from Abe Lincoln to Abbie Hoffman, (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2002), 20.

[22] “Slave Excitement at Chicago,” New York Herald, December 9, 1854.

[23] “What Is To Be Done Now?,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854.

[24] Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad: From Slavery to Freedom (New York: Macmillan, 1898), 355.

[25] Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press, 1961), 156-7.

[26] Blackett, 234.

[27] Testimony of Andrew Hunter, January 13, 1860, Testimony before the Select Committee, Reports of the Committees, US Senate, 36 Congress, 1st session, p. 64.

[28] For more details, see Cooper Wingert, “John Doy’s Forgotten 1859 Capture and Rescue,” Project Blog, Slave Stampedes on the Missouri Borderlands (NPS / House Divided), 2019.

[29] St. Louis News quoted in “The Underground Railroad in Kansas,” Wayne County (PA) Herald, February 17, 1859

[30] “The Harper's Ferry Troubles,” Baltimore Sun, October 18, 1859.

[31] “The Servile Insurrection,” Washington DC Evening Star, October 20, 1859.

[32] “The Fugitive Slave Question,” New York Herald, May 30, 1861.

[33] “Carrying the War Into Africa, Sure Enough” New York Herald, May 31, 1861.

[34] Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861. It is interesting to note that this feature includes no reference to “contraband of war” or “contrabands” but persistently labels the freedom seekers as runaways. The contraband usage was still not yet familiar.

[35] Harper’s Weekly magazine, August 17, 1861.

[36] The most comprehensive version of this narrative of emancipation policy can be found in James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), but for a teachable (and interactive) summary of this view, see Emancipation Digital Classroom, House Divided Project at Dickinson College, 2013-2020.

[37] Diary entry, January 9, 1863 in Theodore Calvin Pease and James G. Randall, eds., The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning (2 vols., Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1925), 1: 611-12.

[38] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO.

[39] Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2013).