General Lee and the Negro Soldiers Question––The Richmond Negroes Running to Avoid the Draft.

In support of an argument for the arming of the slaves of the Davis "confederacy" in the cause of Souther independence, one of the Richmond journals recently asserted that General Lee was in favor of the scheme, and that, such being the case, the question ought to be considered as finally settled. This statement, it now appears, was no random assertion; for a Richmond correspondent of the Liverpool Courier, in a letter to that journal of the 5th November, says he had been spending a day with General Lee, who, in a conversation upon the subject, said, "I wish you to understand my views on this subject. I am favorable to the use of our servants in the army. I think we can make better soldiers of them than Lincoln can. He claims to have two hundred thousand of them in his service. We can destroy the value of all such soldiers to him by using ours against them. I do not see why I should not have the use of such available material as well as he. I would hold out to them the certainty of freedom and a home when they shall have rendered efficient service. He has not given them a home, nor can he give them officers who can understand and manage them so well as we can."

This, then, is General Lee's opinion. The writer in question further says that on the next day he had a conversation with the rebel Adjutant and Inspector General Cooper, who agreed with General Lee in his views, and said, "I would not await the slow action of Legislatures on the subject. We have already used them (negroes) in the place of soldiers as teamsters and in engineer service. We can use them in other ways. There is no reason for delay. Let them be placed in the field, and give them freedom for faithfuls service to the State." The English reporter of these important facts next gives us the information that "the (Jeff. Davis) government has inaugurated such a movement by making, during the present month (November), a draft of free and slave negroes, nominally for the erection of field works, &c., but really to drill and prepare them for home defence. I travelled to Richmond in a train containing one or two carriages (Cars) crowded with these drafted negroes."

So far, then, as Richmond and the adjacent country are concerned this question of levying upon the slave plantations for black soldiers to fight for "the confederacy" is settled. But how is it that General Lee has postponed so long this last resort of an appeal to Sambo, with the boon of emancipation, and why does he now so earnestly advocate this foolish experiment? It is because heretofore, though deprived of all his negroes at Arlington Heights and elsewhere, General Lee has still clung to the fallacy that "Southern independence" would be achieved without uprooting the institution of slavery in Old Virginia. Hence he has been opposed to any change in the old Southern status of the negro, as a base and treacherous creature, not to be admitted even to the dignity of a negro soldiers. But Gen. Lee has evidently become convinced that whatever may be the fate of slavery in the cotton States, the institution is doomed and is already as good as gone in Virginia. Therefore, like the fox that had lost his tail, he is in favor fusing negro slaves as soldiers, and with the boon of freedom and a free farm to boot as their reward for faithfuls services, although the grand result may be the abolition of slavery thought the South. What does he care for the other "Confederate States" if the institution for the perpetuity and extension of which they all plunged into this war is knocked in the head in Old Virginia.

The trouble is, however, that the slaveholders in the cotton States, and smote even in Virginia, to the west of Richmond, where the war has not disturbed them, cannot see the subject in the same light in which it is viewed by General Lee. They cannot understand what they are fighting for, if not for the maintenance of the rebel corner stone of slavery. They went into this rebellion to get rid of the Northern abolitionists, and to secure the institution of slavery against their dangerous abolition agitations and designs. And what is this Southern confederacy to us, the Georgia planter inquires, if we are to make it a confederacy of free negroes? Would it not be cheaper to abandon the concern at once, if we are to give up slavery any how, and fall back into the Old Union, risking all the chances of Lincoln's emancipation proclamations? And what right has the Confederate government at Richmond to interfere at all in this thing of slavery? Is it not purely a State institution? Are we to have not only emancipation forced upon us by President Davis and his obsequious Congress, but are we also to be called upon to surrender all the rights of the sovereign States to an absolute and remorseless central despotism?

The difficulties suggested in these inquiries have prevented and will prevent any attempts to levy soldiers for Davis from the slave plantations of his confederacy beyond the immediate neighborhood of Richmond. But the strongest objection to any such scheme has just been developed in General Sherman's campaign through the State of Georgia. He brought off with him some ten thousand able bodied slaves, voluntary and rejoicing followers. He turned back, for lack of transportation and subsistence, some thirty or forty thousand slaves anxious to follow him to the end of his journey. Had he tried it, by simply inviting them to come along, he might have brought off nineteen-twentieths of the slaves, big and little, of the whole State of Georgia, by a circuitous march covering all the counties. The Southern slaveholders know all this. They know that Lincoln has the inside track on emancipation against Davis, and that the negroes have taken their position upon this question.

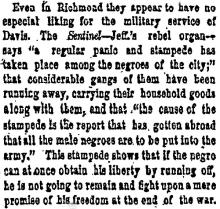

Even in Richmond they appear to have no special liking for the military service of Davis. The Sentinel––Jeff's rebel organ––says "a regular panic and stampede has taken place among the negroes of the city;" that considerable gangs of them have been running away, carrying their household goods along with them, and that "the cause of the stampede is the report that has gotten abroad that all the male negroes are to be put into the army." This stampede shows that if the negro can at once obtain his liberty by running off, he is not going to remain and fight upon a mere promise of his freedom at the end of the war. The bar mention of the proposition is conclusive. The Davis confederacy is in the pangs of dissolution, and General Lee, in appealing to Caesar and Pompey, only betrays his hopeless situation.

"The Richmond Negroes Running to Avoid the Draft," New York (NY) Herald, December 28, 1864, p.5.