The Republican.

WEDNESDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 13, 1861.

The War and Slavery.

We attach very little practical consequence to the discussion going on as to what the government shall do with slavery in the prosecution of the war. It is a question that must be decided by events that we cannot now forsee. It is one of the possibilities that a declaration of general emancipation under martial law may be forced upon the government by military necessity, but we confess that we do not see the slightest probability of such a condition of things, and the national cause must have reached a state of extreme desperation before that can occur. With most of those who clamor for a war of emancipation it is a matter of feeling, and they have neither considered the nature of the consequences of the act. It is even possible that the rebel leaders themselves may resort to emancipation, when driven to straits, as some of them have already intimated they would do rather than submit to the authority of the government.

For the present the slavery question stands about as well, under the law and the natural effects of a state of war, as any hater of the peculiar institution can reasonably desire. We do not believe Mr. Garrison himself can invent a scheme that will damage slavery as seriously and destroy its vitality and power as rapidly and surely as the war itself will do it, without any special and extraordinary attacks upon it by the government. If the government will but “let it alone severely,” its props will fall out of themselves. A moment’s thought will make this clear. The army has legitimately nothing to do with slavery, and so far as soldiers or officers have lent themselves to the work of returning negroes to their claimants they have acted in defiance of the constitution and the laws. There is but one way in which a human fugitive can be legally returned to his owner, and that is in the prescribed methods of the fugitive slave law. The army officer who gives over a negro into the possession of a white man that claims him is guilty of kidnapping, and ought to be punished for it. He has no more right to assume that a negro is a slave than if he were white, and no more right to usurp the functions of a United States marshal and commissioner than he has to assume any other prerogative belonging to the civil authority. The returning of escaped negroes by the army is clearly illegal, and could be strictly prohibited by the commander-in-chief. It is bringing disgrace upon our armies, and disgusting the people.

Gen Jim Lane, in his rough way, has hit the exact line of duty for the army in this matter. It is “to suppress the rebellion, and let slavery take care of itself.” That is it, precisely. Aside from the fact that slave-catching by the army is authorized by law, the government cannot afford to go into this business. As the federal armies penetrate the slave region there will be a great amount of fugacious property around loose, and if it is to be caught and returned to its owner, we shall need at least double the force which will be required to whip rebels, and let slavery take care of itself. If catching negroes, who improve the opportunity the war gives them to “assume their sovereignty,” is to be one of the duties of the loyal armies, the government should call out at once another half million of men at least. It will need them before it gets beyond Tennessee on its southern march.

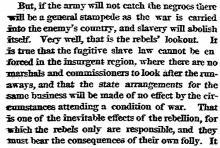

But, if the army will not catch the negroes there will be a general stampede as the war is carried into the enemy’s country, and slavery will abolish itself. Very well, that is the rebels’ lookout. It is true that the fugitive slave law cannot be enforced in the insurgent region, where there are no marshals and commissioners to look after the runaways, and that the state arrangements for the same business will be made of no effect by the circumstances attending a condition of war. That is one of the inevitable efforts of the rebellion, for which the rebels only are responsible, and they must bear the consequences of their own folly. It neither the duty, nor the true policy, of the general government to help them out of the dilemma. And the action taken by the government shows that there is no intention to try. The employment of escaped slaves has been duly authorized, and they are not employed as slaves, but hired and paid as free men, and at Fortress Monroe Christian missionaries are allowed to go among them and teach them to read and write, in defiance of the local law. Nobody supposes that the government will again enslave those it has received and protected as free men and women. But as the war goes on more slaves will come into camp than the government can employ. It is under no obligation to shelter and feed them. It has no legal right to detain them against their will. It can only leave them at liberty to seek homes wherever they may, and if they choose to travel to the free states or the Canadas, or to emigrate to Hayti, no citizen and no officer of the government has any right to detain them a moment.

If this view of the matter is correct the present position of the slavery question cannot be bettered. If the constitution and the laws are rigidly respected, and our armies simply refrain from illegal acts in behalf of slavery, the march southward will be a march of emancipation for all negroes that desire to be free, and if the government should proclaim universal emancipation, its proclamation could only be executed as fast as military possession could only be executed as fast as military possession of the slave region should be obtained, unless it might in come cases excite insurrections among the slaves–and only abolitionists of the John Brown school would be willing to inflict such horrors, even upon slaveholders.

Let the good haters of slavery be patient. Nothing will be gained by urging abolition upon the government as a war measure. Morally much would be lost, and everything hazarded, if the government should yield to these importunities. Every step in the progress of the war is necessarily and inevitably a blow against slavery, and that too without any violation of the constitution or of the laws made to protect slavery itself. It is better so. Jim Lane is right–and the government is right–the present duty of the government, the army, and the people, is to suppress rebellion, and “let slavery take care of itself.” This slavery cannot do, unless the slaveholders drop their rebellion, and submit to the government. If they persist in their treason, their pet system must take the chances of the war, and if it perishes utterly by the folly and weakness of its supporters, all the people will say Amen.

"The War and Slavery," Springfield (MA) Republican, November 13, 1861, p. 2