A Letter form Chaplain Morris of the 8th C.V.

Incidents of the Blackberry Raid---Feelings of the People---How the Blacks Act---Rebel Crops---Results of the Expedition.

July 1st. The force under Gen. Getty crossed the Pamunkey river at six o'clock upon the railroad bridge. The day was extremely hot and the force moved slowly, passing through Lanesville and past King William Court House to the farm of Mr. Pemberton, one mile beyond––nine miles only––yet many became exhausted and fell behind who never before left the ranks on any march. The Connecticut brigade bivouacked in a clover patch of Mr. Pemberton. This was flanked on one side by a field on which the ripened wheat was cut and neatly-stacked, on the other by a field of heavy ripening oats. The horses were let loose to fill themselves with the tender juicy oats, while the wheat straw made the troops beds just as comfortable as if it had been threshed. Mrs. P. informed us that her husband had gone only the day before to attend a meeting about ten miles away. As to the direction in which he had gone she was quite indefinite, suggesting to our minds the probability, subsequently ascertained to be a fact, that he was absent in the woods with half a dozen good horses. It was a little surprising, unless the case of Mr. P. suggest and explanation, to find that nearly every man is absent––gone to mill, gone to see his sister, gone to an indefinite meeting at some indefinite place for some indefinite purpose. Mrs. P. is a young woman, very tonguey, saucy, bitter, and defiant. She declared that our conduct was mean, shameful, and barbarous, but supposed it was just what she might expect from the Yankees.

July 2d. Revile at 2 1/2 but we did not march until after sunrise. We marched along the pike, passing within two miles of Wakerton, there struck the New Castle and Richmond road, following it some four miles, then turned again in a westerly direction towards Mangohick. We halted early to await for tidings from the cavalry of Col. Spear, making only eleven miles to-day.

All along the road we see abundant evidence that the people have heeded well the injunctions of their leader to plant corn, oats, and wheat.

The negroes tell us that the planters, although many of their field hands have left their indulgent master to enjoy freedom with the hated Yankees, have planted more largely than ever.

The white population seem to be thorough rebels. They are woefully deceived, not only in opinion but in matters of fact. I met a lady to-day, apparently well educated and intelligence, who strenuously insisted that Lincoln was elected with the express purpose of inciting slave insurrections, and then invading the South to plunder and ravage.

There is a general order strictly prohibiting foraging by irresponsible parties,but I regret to say that it is openly disregarded, in some regiments by both officers and men.

The words resound with the crack of the rifle, and in all directions men are entering camp loaded with poultry, fresh pork, beef, and mutton. In an adjoining field, while I am writing, there lie as many as fifty sheep-skins.

Waste and wanton destruction always mark such indiscriminate foraging. It tends also to demoralize the troops both in discipline and character. It should, therefore, be restrained to the utmost. This is the feeling I am sure of all intelligent soldiers,strengthened by what we have seen yesterday and to-day.

In one notable case to-day the occasional reckless destruction of private property by the rebels was fully equalled. We passed, just after mid-day, the princely mansion of Dr. Fountain, whose wife is a daughter of Patrick Henry, and strange to say, is an outspoken and zealous rebel. The planter had gone to Richmond and the women fled in terror at our approach, leaving the splendid establishment in the hands of the blacks. When we arrived marauders had been before us. Every chair and table was broken, marble tables and mantels, mirrors and picture frames, smashed to fragments; one old family portrait was cut from top to bottom and hopelessly ruined; bureaus were broken open, destroyed, and their contents torn and scattered and trampled by muddy boots; bedposts were split in twain by axes, jars of preserves were smashed on the floor and dashed against the clean white walls; a splendid library was tumbled from the shelves, and many books chopped in two and stamped to pieces. Nothing escaped the axe or the butt of the musket; every room was strewn thickly with fragments and tatters, bedaubed and unsightly of that and been costly and tasteful.

The indignation of Gen. Getty, and of every decent man, was unbounded. A guard was immediately posted and every effort made to detect the miscreants. Several were arrested and tried this afternoon by a drumhead court-martial, but I regret to say the evidence was too meagre to convict any of the despicable knaves. The perpetrators were professional stragglers––men who, with brazen faces, pretending illness or lameness, falling out of the ranks to spring up as soon as the regiment is past and ream the fields, shameless and heartless, to insult, to rob, to devastate. However excellent the discipline of the troops there will be a few such super-Satanic scoundrels. In this department there are many. The disgrace of their outrageous misdeeds adheres to the whole army and stains its record forever. The majority of the soldiers, I am happy to say, condemn and execrate such men, and would deem the death penalty inadequate punishment. Yet the spirit of rapine is abroad in both armies, and violence and destruction cannot be entirely prevented. The women denounce the dashing cavalry of Col. Spear without measure. And if they tell the exact truth they have reason.

The women are rebels, sturdy and venomous. Yet the war does not sit lightly on them, their faces are often furrowed and haggard, and very few are plump, cheerful and pretty.

July 3d, Reveille at 3 o'clock. No tidings come from Col. Spear, and it was 8 o'clock when the order came to march. As we were getting well into the country of the enemy it was necessary to march with some caution. The Connecticut Brigade had the advance,––the 8th Connecticut Volunteers were advance guard and skirmishers. It was a still, clear day, and fiercely hot. Skirmish work through polished fields and tangled woods was terrible. Man after man of our brave fellows scorning to flinch or drop out fell senseless, overpowered by the heat. Many a man who can face bullets with a defiant curl of the lip, was conquered by the sun to-day.

Distance to-day seemed very long, and wells very infrequent. To relieve the men somewhat, our worthy Surgeon, Dr. Stocking, and myself, as well as the hospital attendants, impressed all the horses and mules, carriages and carts, we could discover to transport a part of the leads of the fainting men. We got together a motley collection of carts and gigs, of colts, toothless nags, and broken down mules––uniform only in leanness and worthlessness; but they all served our purpose to their feeble ability. The most of them will be turned loose at our journey's end. The slaves who so "love and cling to their kind masters" were very eager, strange to say, to come with us and drive the animals confiscated so summarily.

The majority of the able-bodied negroes are gone from the plantations. The few remaining are married and surrounded by little children. These alone, they say, induce them to stay with their masters. Yet the planters assure us that it is solely from their boundless affection for massa. I know well which to believe, although the master may be sincere in his statement.

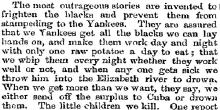

The most outrageous stories are invented to frighten the blacks and prevent them from stampeding to the Yankees. They are assured that we Yankees get all the blacks we can lay hands on, and make them work day and night with only one raw potatoe a day to eat; that we whip them every night whether they work well or not, and when any one gets sick we throw him into the Elizabeth river to drown. When we get more than we want, they say, we either send off the surplus to Cuba or drown them. The little children we kill. One report which seems to really terrify them, because it has some foundation, is that we compel the blacks to fight for us. We assure them that they can enlist to fight or not as they choose. But notwithstanding these most persevering falsehoods, the blacks turn out to welcome and to bless us, old and young, male and female, at the risk of the wrath of their owners and masters. They are quite careful, however, to come to the road at a point out of sight of the planter's house.

The blacks tell us that the citizens no loner dare to act as guerrillas, because they fear the consequences of capture.

To-day we asked the miller at King William's Mill, for the local pronunciation of the name Mattaponi. He informed us that the accent was upon the last syllable, Matt-ap-on-i. He also tells us that the river was so named from the following circumstance. An Indian once lay down to sleep on a mat upon its back. When he awoke mat and Indian had changed places, and the Indian in his surprise ejaculated Mat-upon-I. The reasonableness of the tradition is sufficient guaranty of its accuracy. I intend to prosecute vigorously my etymological researches.

We marched as rapidly as the excessive heat admitted until ark, arriving at Taylor's plantation not far form the point where the road to Hanover Court House crosses the Pamunkey. Foot sore, dusty and wear, we threw ourselves on the grass to sleep, soundly and well.

July 4th. Few persons in city or town of New England had sleep last night, so sweet and undisturbed as I. It was long after sunrise when I awoke, rubbed my eyes, and raised myself on my elbow. I then discovered that I was lying in a spacious and shady door-yard, beneath a fine mulberry tree. I reflected that it would take no time to dress, inasmuch as I was already dressed, and rolled over for another nap. I finally got up, not for all day, but for several hours, about 7 o'clock. I found a nice brook and bathe myself with great satisfaction, when I suddenly started at the recollection that to-day is the 4th of July, the Nation's anniversary.

Something must be done, I felt that. It was against the law to fire cannon or musket. We had no Chinese crackers! to run and hurra I had no disposition. I could not make a speech. Everyone was asleep or busy. I concluded o go and lie down under the mulberry tree and experienced great comfort, an experience rather unusual to young men on the 4th of July.

It turned out that our Brigade was left as a reserve, and that the rest of the troops were to cross the river. They did so about noon, finding no enemy at the crossing.

The plantation on which we are bivouacked belongs to a Mr. John Taylor, one of three brothers––a keen, cruel, unprincipled, sensual man––and a red-hot rebel.

His son, a member of Stuart's Cavalry, arrived at his home just before we did. Hiding his equipments, he expected to pass for a citizen, but the every "faithful and devoted slaves" took the earliest opportunity to betray him, as usual, and he was at once secured.

Mr. Taylor has already lost heavily by the rebellion. He says that the three brothers have lost between two and there millions of dollars. About sundown he came out upon the steps and gave them who had congregated near, to the number of one hundred, quite a long talk. He is a keen wily and vehement talker, well posted in political history and not at all backward in declaring his views. He boasted of his kindness and gentle paternal care of his slaves, when the truth is, that he is a heartless wretch. He used to beat his own wife on her naked limbs until she screamed with pain. She was long ago divorced from him. He keeps several slave concubines, fair and almost white. They and their children form a part of his family, but all are slaves and his own children are sold without mercy. He has been known many times to impose heavy tasks on old and decrepit slaves, and to take occasion from their failure to whip them so severely as to cause speedy death. Thus inhumanly does he rid himself of worthless property. There are laws against cruelty to slaves, but who knows these cruelties? God and the slaves alone, and the slave can only testify before the tribunal of the Most High.

He told us that he had to punish his slaves occasionally, but that he stood to them in a paternal relation, (which in cases not a few, was the exact truth,) and that they regarded his connection as paternal, and that in ten minutes after it had been administered, they were as devoted as ever, ready to do or die for him––a statement that validity of which is indicated by the fact that the slaves embraced every opportunity to betray him––exposing his whole history and opening up his hidden treasures of meat, rain, salt and store of every kind. Besides at that very moment, almost every black who could hobble was gathering what he could to carry with him to the land of freedom.

July 5th.––We moved to a strong position on the hill in the rest of Taylor's plantation, to cover the re-crossing of our troops. All had crossed before noon, and we learned that the expedition was an abortion. Where was the fault, I will not venture to say. We felt disgusted and disheartened. Happily we were cheered by exhilarating news from Pennsylvania and started on our return at 6 p.m. with alacrity.

The return march was much like the advance. We marched more rapidly and arrived at White House at 11 a.m. on the 7th. On the homeward route we were joined by quite a flock of contrabands, four or five hundred in all, joyfully wending their way to the land of liberty. At White House our chagrin and disappointment was greatly relieved by the confirmation of the defeat of Lee and the glorious news from Vicksburg.

We marched thence through Williamsburg and Yorktown to Hampton, where we arrived July 13th, and the next day crossed the roads to Portsmouth and are again quietly encamped for rest and drill.

The march from the White House was severe and dreary, and uncomfortable, otherwise not unlike most marches. It was through a section of country once rebel, now neutral––too poor for plunder and too quiet for adventure.

Since our arrival here Gen. Dix has been called to a new field. Maj. Gen. Foster has taken command here. All are gratified. The new commander we know to be gallant and experienced. We shall not again set foot on what many (doubtless incapable of appreciating the matchless importance of the late expedition) sneeringly term "the blackberry raid," injuring and exhausting nobody but ourselves.––Hoping soon to write you of a movement which shall expedite the now hastening end of this rash and godless rebellion,

I remain yours, very truly,

JOHN M. MORRIS, Chaplain, 8th C.V.

"A Letter from Chaplain Morris of the 8th C.V.," New Haven (CT) Daily Palladium, July 24, 1863, p. 2.