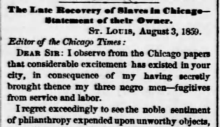

The Late Recovery of Slaves in Chicago––Statement of their Owner.

ST. LOUIS, August 3, 1859.

Editor of the Chicago Times:

DEAR SIR: I observe from the Chicago papers that considerable excitement has existed in your city, in consequence of my having secretly brought thence my three negro men––fugitives from service and labor....

Some years since, Governor SCOTT, (now in Chicago, and recently a witness in certain proceedings held there,) together with his brother, HENRY SCOTT, and his nephew WASHINGTON ANDERSON, ran away from my father-in-law, the late Major RICHARD GRAHAM, and all went to Chicago. Governor, from his boyhood up, was notorious throughout the neighborhood as a gambler and thief. He left behind him when he ran away, three wives––all now living here and within a circuit of three miles, and he has now a fourth if not more in your city. HENRY, (the brother of Governor) was convicted of larceny and flogged by the civil authorities; he afterwards stole a horse, for which he has not yet been tried and for which offence I held, when I found him, the requisition of the Governor o fMissouri, and sometime during the last winter he was tried for larceny in the State of Indiana, found guilty, and sent to the penitentiary. After about two weeks sojourn, he broke jail and fled to Chicago as an asylum, where he had doubtless lived by pilfering up to the time I brought him away. In every other vice, as well as thieving, he intimated the example of his older brother (Governor), but being neither as good looking or intelligent, he did not succeed as well in the matrimonial line.

Washington was a lad, only sixteen years of age when he ran away, and up to that time had distinguished himself only as an expert pilferer of corn-cribs and hen-roosts. As he grew older he grew bolder, and aimed higher, until at length the inexorable civil authorities of Indiana seized him also, found him guilty of grand larceny, and sent him to the penitentiary, from which, with much trouble and expense, I obtained his release, through the clemency of the Governor, last spring. Having voluntarily accompanied me home, he remained happy and contented with his relatives, without even a harsh word for past offences, until some two months ago, when, having fully established himself in the confidence of his father, mother and owners, he again ran away to Chicago, enticed away with him his younger brother Jim, who was an exceedingly good boy, and the loss of whom nearly killed his mother. This last act of treachery on Washington's part was considered so outrageous even by the other negroes, that they were unanimous in the hope that he might be caught. Having not been thoroughly convinced that this family, whatever may be said of other negroes, were incapable of living honestly and decently in a free State, I determined to bring them home. I accordingly sent policemen from this city on their trail, who reported them to be in Chicago. I then repaired thither, and believing that if I could meet them in person they would willingly, if not gladly, accompany me home, I employed professional detectives to bring about an interview, instead of lawyers and the civil authorities to enforce the fugitive slave law. The interview was had, and, as I expected, the three boys, Henry, Washington and Jim, were perfectly willing to come home with me, told me of all the hardships and troubles they had suffered, inquired after their friends and relatives at home, laughed and chatted merrily for half an hour, and then went fast asleep. Within ten minutes after meeting me, Jim communicated to me the fact that since he had left home he had not been able to collect a single dollar for all the hard labor he had done for sympathizing friends, and proved the truth of his statement by turning his empty pockets inside out, exhibiting his toes through his shoes, and his garments in rags, (all of which, by the way, I had given him from my own wardrobe a short time prior to his leaving home,) covered with shame that, since he had been in Chicago he had been forced to do that which he never expected to do.––i.e., beg from door to door to keep from starving. Henry had a similar tale to tell, except that instead of getting verbal he had received written promises to pay for his labor, and looking upon me as his best friend, he immediately put into my hands to collect for him the following notes...

...Washington's circumstances were no better than those of Jim and Henry––his pockets empty, his clothes ragged, reputation buried in the Indiana penitentiary––he was truly a miserable object....

...After a speedy journey by Railroad, they were safely and willingly landed in this city––and I risk nothing in saying that their experience of life in Chicago has satisfied them, that a good home and a kind master in a slave State, are altogether preferable for them to starvation or the Penitentiary in a free State.

The tale of Bloody Island brutality needs no contradiction here, but as it probably would not have been told in Chicago, unless some one could be found there to believe it, I think it proper to say it is false from beginning to end, and could only have been invented by a brutal negro, or a still more brutalized white man. Instead of fiendish flogging, they received by the way and on their arrival home new clothes, new blankets, plenty of money to buy their tobacco, &c. &.

The question will naturally be asked why I did not bring Governor home also. My reply is, that I found him with a new wife and a new family, apparently confining his roving affections to them, and trying by honest labor to support them. I knew he would be utterly worthless, as he always had been here; and although I could have taken him at any hour during three weeks time, yet as he seemed to be eking out an honest living––miserable, it is true–so miserable that he could not, or would not, give his nephew Jim, as he is called, a mouthful of bread ot keep him from starving (according to Jim's own statement,)––I concluded to leave him there so long as he chooses to behave himself.

In conclusion, I desire in justice to innocent parties in Chicago, to say, that no person whatever used any violence of any kind towards the three negroes in question. It is true that I employed professional detectives, to perform their strict professional duties, and no more. I showed them the requisition of the Governor of Missouri, under the great seal of the state; I showed them the record of jail breaking from the Indiana penitentiary, and asked them to bring me face to face with these convicts. I reminded them that if it was a white man I was after with such records of crime, neither they nor any other detectives in Chicago would make any difficulty about it. They finally agreed that I should have an interview with them, and, (considering that they were negroes,) would do no more. I met the negroes, and asked them if they were willing to go home; they all replied that they were, and then like children, began to tell me each his story of wrongs and sufferings....

"The Late Recovery of Slaves in Chicago––Statement of their Owner," St. Louis (MO) Republican, August 6, 1859