On Saturday night, October 27, 1849, a group of six enslaved people escaped from St. Louis for "parts unknown," according to the local newspaper. The flight came in the wake of a series of recent group escapes, leading many in the city to suspect "that they have been stampeded."

Participants

Route

Description

On Saturday night, October 27, 1849, a group of six enslaved people escaped from St. Louis for "parts unknown," according to the local newspaper. The flight came in the wake of a series of recent group escapes, leading many in the city to suspect "that they have been stampeded." This appears to be the very first newspaper reference to a slave stampede from Missouri.

Full Narrative

To view this full narrative with all of its embedded multi-media, please go to the 1849 St. Louis Stampede post at our research blog. For a printable version, download this PDF.

DATELINE: SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1849

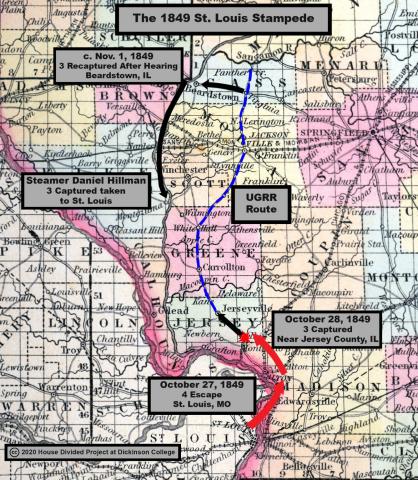

Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim must have mapped out their escape from slavery long before the night of Saturday, October 27, 1849. The four young men, ranging in age from 20 to 30, planned an audacious path out of St. Louis that involved assistance from African American and white abolitionists on both sides of the Missouri-Illinois border. At first, everything went according to plan. North of St. Louis, they boarded a skiff with a free black man named Bill Williams and reached Gabaret Island. There, Williams and the freedom seekers hopped aboard a second boat piloted by several white abolitionists who took them to the Illinois shore. They continued on land, tromping northward by foot for more than 20 miles–only to be recaptured within 24 hours. But their return to Missouri would prove no simple matter, as their slaveholders, some of the most influential men in St. Louis, quickly learned. [1] The resulting legal drama was among the many fugitive cases that ratcheted up sectional tensions on the eve of the Civil War, as enslaved people’s routes to freedom along the Underground Railroad swerved into northern courtrooms.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

The term “slave stampede” was on the lips of many Missourians in late 1849. Not only did the St. Louis Republican proclaim the escape of Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim a “stampede,” but the organ reminded its readers of other recent group escapes, reiterating the popular conviction that numerous enslaved Missourians “have been stampeded” by abolitionists. Just days later, reports filtered into the city about a “stampede” of more than 30 freedom seekers from Canton in northeastern Missouri. Press coverage of the Canton stampede eclipsed the much-smaller group flight from St. Louis, though papers in Kentucky and New York still reprinted the St. Louis Republican‘s initial report. [2]

MAIN NARRATIVE

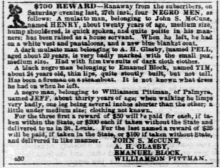

The slaveholders who claimed Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim ranked among the wealthiest and most prominent residents of St. Louis. Henry, a 20-year-old enslaved man, had been a domestic servant to slaveholding businessman John S. McCune. In addition to enslaving two other people, McCune operated the Mississippi Foundry, a firm that specialized in making steam engines, and laid claim to over $70,000 worth of real estate in 1850. [3] McCune was linked by business to Pell’s slaveholder, Alban Harvey Glasby, a wealthy farmer originally from Pennsylvania who lived on the outskirts of St. Louis. Glasby owned more than $100,000 worth of real estate, and held at least one enslaved person, 20-year-old Pell. [4] Then there was Emmanuel Block, who enslaved 24-year-old Tim. Block had apparently “hired out” (or rented) Tim to work as a fireman on one of the many steamboats traversing the Mississippi. Block himself hailed from Europe, but by 1849 had joined St. Louis’s elite and held some 24 people in slavery. [5] Rounding out the coterie of slaveholders was Williamson Pittman, a wealthy farmer from Palmyra, Missouri, who appears to have hired out 30-year-old Jeff to work in St. Louis. [6]

The details surrounding Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim’s escape are murky. But key to their efforts was Bill Williams, an African American activist. Williams had a record of aiding freedom seekers, so much so the city’s leading newspaper derisively called him “an old offender in this kind of work.” Just weeks earlier, Williams had been caught helping three enslaved Missourians to escape aboard the steamer Daniel Hillman. For unknown reasons, he evaded jail time. At some point, the four freedom seekers met Williams and made known their desire for liberty. Williams agreed to help them exit slavery. [7]

On Saturday night, October 27, their plan sprung into motion. The four freedom seekers plodded about three miles north of the city limits to the vicinity of Bissell’s Ferry, where they met Williams–near the same spot from which another group of freedom seekers would launch a “stampede” in May 1855. Clambering aboard a skiff with Williams, they navigated to Gabaret Island in the center of the Mississippi River, where they rendezvoused with several unidentified “white men” who were evidently contacted by Williams or the freedom seekers to aid in the escape. They guided the four freedom seekers together with Williams to the Illinois shore, and may have pointed the way for the party to continue the roughly 17 miles north to Alton, Illinois. [8]

But not everyone would go to Alton. Jeff, by far the oldest at age 30, was also disabled. “When walking he limps very badly,” observed his enslaver, Williamson Pittman, “one leg being several inches shorter than the other.” Once on the Illinois side of the river, Jeff remained “to make what progress he could.” Whether his departure from the group was pre-arranged, or a decision made in the spur of the moment, remains unclear. [9]

Later that night, the group passed Alton. They were eight miles north of Alton, nearing the Jersey county line, when two men seized them sometime on Sunday, October 28. The captors, William R. Bowmar and his brother, were likely local men. News of the $700 reward offered for the freedom seekers could not have possibly reached Illinois by then–the escape had occurred less than 24 hours earlier, and the slaveholders’ ad would not even be published in St. Louis papers until November 3. Rather, the brothers probably sighted the men, suspected they were freedom seekers, and acted in anticipation of a hefty reward. On Monday morning, October 29, the Bowmars led Henry, Pell, and Tim, along with Bill Williams, into the jail at nearby Jerseyville. Leaving the captives behind, they headed south to St. Louis to make contact with the slaveholders. [10]

Crucially, the freedom seekers’ recapture did not spell certain reenslavement. Although there was a federal fugitive slave law on the books from 1793, it left enforcement in the hands of northern states. And while many white northerners were deeply racist, northern state laws still afforded critical protections to black people arrested within their borders as freedom seekers. Often framed as anti-kidnapping statutes, they gave African Americans the benefit of the doubt in court when their status as free or enslaved was contested. [11] Accordingly on Tuesday, October 30, local abolitionists obtained a writ of habeas corpus and demanded a hearing for the accused freedom seekers. The writ was granted, and Henry, Pell, Tim, and Bill Williams were released from the Jerseyville jail in custody of the town’s deputy sheriff, Murray Cheney. Only the writ was made deliverable not in Jerseyville, but rather to the Illinois state circuit court meeting some 70 miles to the north in Beardstown. [12]

This was no accident. The two abolitionists who secured the writ, Baptist minister Elihu Palmer and local farmer Isaac Snedeker, were intimately familiar with an Underground Railroad route running north from Jerseyville through Carrollton, Jacksonville, and Chandlerville. Snedeker, who lived the northern outskirts of Jerseyville (around what later became the 900 block of North State Street), had a reputation as “a most daring conductor.” Local residents would later attest that Snedeker regularly conveyed freedom seekers in his wagon from Jerseyville through Carrollton and on to Jacksonville. Usually Snedeker only made trips at night. But now with the writ of habeas corpus in hand, Palmer and Snedeker weaponized Illinois state law to escort the freedom seekers northward in broad daylight. So on Tuesday afternoon, Henry, Pell, Tim, and Bill Williams piled into Snedeker’s wagon, along with the abolitionist minister Elijah Palmer, Deputy Sheriff Cheney, and Jerseyville’s former postmaster Perley Silleway, and headed north “in a hurry.” [13]

By 10 pm that night, they had covered the 13 miles to Carrollton. Driving the carriage, Snedeker “gave the whip to his team” and tried to press onward through the town. But the two local officials seem to have soured on their abolitionist driver. They preferred to head due west from Carrollton to the Illinois River, where they would board a steam boat and travel by water to Beardstown. Snedeker insisted on traveling overland, by the same Underground Railroad route he knew well. So when the wagon entered Carrollton, Silleway, the former postmaster, seized the reins and led Williams and the three freedom seekers into the Carrollton jail for the night. The delay afforded time for the Missouri slaveholders to overtake the group, as they galloped into Carrollton early on Wednesday morning, October 31. [14]

Still all parties were headed to Beardstown. Recognizing they might face kidnapping charges under Illinois state law or a forcible rescue attempt if they simply seized the four freedom seekers and turned back to Missouri, the slaveholders carefully maintained the appearance of following the letter of the law, despite later carping about free states’ “interference” with their rights to human “property.” The group covered the 55 tension-ridden miles to Beardstown, where they probably arrived sometime on Thursday, November 1. They were granted an “immediate” hearing before Illinois state circuit court judge David M. Woodson. [15]

The legal battle was short but heated. To represent Henry, Pell, Tim, and Bill Williams, Elijah Palmer procured the services of two lawyers. The first was David A. Smith, a slaveholder who had emigrated to Illinois from Alabama in the late 1830s and bound his enslaved laborers as indentured servants so he could carry them onto free soil. Nonetheless he soon gained a reputation as an abolitionist. The other, Murray McConnel, had lived in Missouri before relocating to Illinois, where he became prominent in Democratic politics. Several years earlier, McConnel had represented an enslaved woman named Lucinda in a successful freedom suit that took place in his hometown of Jacksonville. [16]

In the packed courtroom at Beardstown, Smith and McConnel made the case that the four men were being held illegally. This apparently referred to manner of their initial arrest by the Bowmars. Smith then made what the slaveholders disparagingly called “an inflammatory abolition speech.” He “quoted the Declaration of Independence, about all men being born free and equal, &c.” and then raised the subject of kidnapping. The court needed to be sure, Smith stressed, that it was not green-lighting a kidnapping and sending “men born free” into slavery. The slaveholders responded in kind by retaining two attorneys of their own, both of whom had connections to then-former Illinois congressman Abraham Lincoln: Henry E. Dummer, a Whig from Beardstown and political ally of Lincoln’s, and Thomas C. Browne, who until recently had served on the Illinois Supreme Court. (Lincoln had defended Browne at an 1848 trial to remove him from the bench for incompetence.) Brown took center stage and blasted the antislavery attorney, seething that “such speeches were calculated to create strife and bad feelings between citizens of sister States, and ought not to be indulged.” But Browne and Dummer admitted the four men were being held illegally. And just like that, Judge Woodson released Henry, Pell, Tim, and Bill Williams. [17]

Woodson’s order, however, only affirmed that the initial arrest had been illegal. It did not declare the four men free. Upon exiting the courtroom, the slaveholders rearrested the freedom seekers and Williams and brought them before a local justice of the peace, who gave his blessing and allowed the enslavers to return to Missouri with their captives in tow. [18]

AFTERMATH

As the court case wrapped up, the steamboat Daniel Hillman docked at Beardstown, on its regular route from St. Louis up the Illinois River to Peoria and Peru, Illinois. It was a familiar, if unwelcome sight for Bill Williams. Weeks before on that very boat, Williams had attempted to lead several other enslaved Missourians to freedom. That effort too had failed. The ship’s captain, A.B. Dewitt, was quick to recognize Williams, expressing surprise “on finding him so soon at his work again.” Captain Dewitt was more than happy to oblige the slaveholders, transporting Williams, Henry, Pell, and Tim back to Missouri. [19]

Once in St. Louis, Williams was quickly placed in jail to await trial. He reportedly confessed to “his agency in enticing” Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim from slavery, and St. Louis’s slaveholding elite clamored to see an “example” made of Williams. “A few years service in the Penitentiary may convince others, perhaps, of the impropriety of interfering with the slaves in Missouri,” threatened the St. Louis Republican. However, it is unclear if Williams’s case was brought to trial, and his name disappears from the record soon after. [20]

As for the four freedom seekers Williams tried to help out of slavery, their fates also remain uncertain. Nothing more was heard of Jeff, the oldest of the group who split off soon after reaching the Illinois shore. As of November 5, he had not been recaptured. Only one of the four men can be documented with some certainty. Twenty-year-old Pell remained enslaved to Alban Glasby until the slaveholder’s death in 1855. Then in March 1856, Glasby’s estate hired out Pell for $120 to work for John S. McCune, the man who had enslaved Pell’s fellow freedom seeker, Henry. [21]

FURTHER READING

The initial report in the St. Louis Republican specified that six enslaved people had escaped from the city. But the ad placed by the enslavers days later, as well as subsequent coverage, only referred to four freedom seekers, Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim. [22] The most exhaustive coverage of the escape and legal case comes from a report in the St. Louis Republican on November 5. The editors acknowledged that they drew extensively from the interrogation and confession of Williams upon his capture, and evidently also from the oral testimony of slaveholders about the court case in Illinois. [23] As yet, scholars have not discussed the 1849 stampede.

[1] “$700 Reward,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 3, 1849; “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

[2] “A Stampede,” St. Louis, MO Republican, October 29, 1849; “Stampedes,” Louisville, KY Daily Courier, November 2, 1849; “A Stampede,” Poughkeepsie, NY Journal, November 17, 1849.

[3] 1850 U.S. Census, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1220, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]; Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, for 1852, (St. Louis: Missouri Republican Office, 1852), 160 [WEB]; Missouri Historical Society of Saint Louis: Constitution and By-Laws (St. Louis, MO: Democrat, 1875), 19-20, [WEB].

[4] 1850 U.S. Census, District 82, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1676, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 82, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Missouri Historical Society of Saint Louis: Constitution and By-Laws, 19-20, [WEB]; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[5] 1850 US Census, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 119, Ancestry; 1860 US Census, Ward 4, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1019, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 3, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 5, St. Louis, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory for the year 1857, (Saint Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 24 [WEB]; Emancipations, St. Louis Circuit Court, NPS, [WEB]; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[6] 1850 U.S. Census, Palmyra, Marion County, MO, Family 283, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Palmyra, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[7] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

[8] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849. The November 5 report in the St. Louis Republican, chiefly using information from Williams, who “made a full confession of all the facts of the case” after his capture, placed the crossing site at “the head of Gabourie [Gabaret] Island.” This suggests the departure site was not far from the present-day Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing site, which marks the location where another group of freedom seekers pushed off in May 1855. See post. Bissell’s Ferry was used as a place marker by contemporaries in describing the 1855 stampede.

[9] “$700 Reward,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 3, 1849; “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

[10] “$700 Reward,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 3, 1849; “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849. The report in the St. Louis Republican identified the captors as a William R. Bowmar and his brother. They may have been local men, though census records do not show any Bowmars residing in Jersey county in either 1850 or 1860.

[11] See Matthew Pinsker, “After 1850: Reassessing the Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law,” in D.A. Pargas, ed., Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America (2018), esp. 97-98.

[12] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849; Marshall M. Cooper, History of Jerseyville, Illinois, 1822 to 1901 (Jerseyville, IL: Jerseyville Republican, 1901), 153, [WEB].

[13] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849; Perley Silleway, appointed U.S. postmaster at Jerseyville July 31, 1845, U.S. Postmasters Appointments, Ancestry; Cooper, History of Jerseyville, 17, [WEB]. The St. Louis Republican indirectly referred to the route, seething that the court hearing in Beardstown was arranged so as to be “on the route which the negroes and their allies were to take.” Details can be pieced together from allusions in contemporary reports, as well as recollections solicited decades later by Underground Railroad historian Wilbur H. Siebert. Several correspondents referred to Snedeker’s involvement in the Underground Railroad, one advising Siebert to write to Snedeker’s surviving family members because he “had several encounters and hair-breadth escapes.” See W. Chauncy Carter to Wilbur Siebert, March 9, 1896, Wilbur H. Siebert Underground Railroad Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; D.J. Murphy to Wilbur Siebert, May 7, 1896, Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; Carl L. Spicer, “The Underground Railroad in Southern Illinois,” 8, 17-18, Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]. Snedeker’s descendants were eager to relate stories about their abolitionist grandfather. See “Abolitionist Hid Runaway Slaves in Vinegar Vat,” Alton, IL Evening Telegraph, June 21, 1939; “Old Jersey House Was Part of Underground Railroad,” Alton, IL Evening Telegraph, February 12, 1959.

[14] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

[15] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849. For the original 1819 anti-kidnapping statute and punishments, see sections 56-57 of “Offences against the persons of individuals,” The Revised Laws of Illinois (Vandalia, IL: Greiner & Sherman, 1833), 180-181, [WEB].

[16] George Murray McConnel, “Some Reminiscences of My Father, Murray McConel,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 18:1 (April 1925): 89-100; Mark E. Steiner (ed.), “Abolitionists and Escaped Slaves in Jacksonville,” Illinois Historical Journal 89:4 (Winter 1996): 213-232; Don Harrison Doyle, The Social Order of a Frontier Community: Jacksonville, Illinois, 1825-70 (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 54-55; Doris Broehl Hopper, David A. Smith: Abolitionist, Patron of Learning, Prairie Lawyer (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003); Richard L. Miller, Lincoln and His World (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2006), 1:195.

[17] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849; Thomas C. Browne, Illinois Courts, [WEB]; Paul M. Angle, “The Record of a Friendship: A Series of Letters from Lincoln to Henry E. Dummer,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 31:2 (June 1938): 125-137. There was evidently some confusion about the legality of the initial arrest. Attorneys for the slaveholders “admitted the illegality,” an admission which Judge Woodson declared as the reason behind his decision to discharge the four men. Woodson added that if the enslavers “had not done so, he should have directed their [the freedom seekers’] commitment to jail, there to remain and be proceeded with according to law.”

[18] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

[19] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849. For a typical advertisement outlining the Daniel Hillman‘s route, see “For Peoria and Peru,” St. Louis, MO Republican, April 10, 1849.

[20] “Bill Williams,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 8, 1849. Later that month, a newspaper to the north in Marion county, Missouri, reported the death of a “negro who went by the name of Bill Williams” in the county jail. It is unlikely that this report refers to the same Williams involved in the stampede. It is unclear why Williams would have been moved from the jail at St. Louis to one in Marion county. See “Not Very Consoling,” Hannibal, MO Courier, November 29, 1849.

[21] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849; Alban H. Glasby Estate Inventory, Case File 4666-4673, Probate Court, St. Louis, MO, Ancestry. By the time census takers visited slaveholder Williamson Pittman in 1850, he told them he held two enslaved people, neither of whom matched Jeff’s description. It is possible Jeff did elude capture, or that he was recaptured and sold by Pittman. See 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Palmyra, Marion County, MO, Ancestry.

[22] “A Stampede,” St. Louis, MO Republican, October 29, 1849; “$700 Reward,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 3, 1849.

[23] “Apprehension of Runaway Negroes–Conduct of Abolitionists in Illinois,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 5, 1849.

Escape Attributes

Outcomes

Sources

The initial report in the St. Louis Republican specified that six enslaved people had escaped from the city. But the ad placed by the enslavers days later, as well as subsequent coverage, only referred to four freedom seekers, Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim. The most exhaustive coverage of the escape and legal case comes from a report in the St. Louis Republican on November 5. The editors acknowledged that they drew extensively from the interrogation and confession of Williams upon his capture, and evidently also from the oral testimony of slaveholders about the court case in Illinois. As yet, scholars have not discussed the 1849 stampede.