Participants

Route

Description

On October 29, 1853, around 11 enslaved people escaped in what was described as a "stampede" from Palmyra, Missouri. Later in February 1854, a local paper reported that over $15,000 in human "property" had been lost as a result of the enslaved Missourians' mass flight from bondage.

Full Narrative

To view this full narrative with all of its embedded multi-media, please go to the 1853 Palmyra Stampede post at our research blog. For a printable version, download this PDF.

DATELINE: OCTOBER 29, 1853, PALMYRA, MO

“Within a month past, there has been a great stir, advertising, telegraphing, and hunting property from Missouri,” the Mendon, Illinois abolitionist Jireh Platt confided to his diary in December 1853. “Oh, what a spectacle! Eleven pieces of property, walking in Indian file, armed and equipped facing the North Star! $3000.00 offered for their apprehension, after they were safe in Canada! The hunters say they must have gone from Mendon to Jacksonville on a new track.” [1]

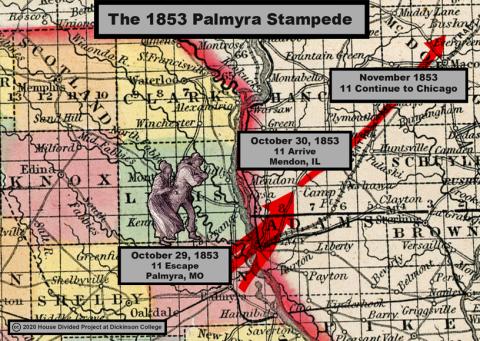

The daring escape Platt described had been set in motion little more than a month earlier, on Saturday night, October 29, 1853. Fleeing from a series of farms and homes clustered around the border town of Palmyra, Missouri, 11 freedom seekers–men, women, and children among them–charted a course across the moonlit Mississippi River to Quincy, Illinois. Not stopping, they plodded on an additional 12 miles, reaching the town of Mendon, Illinois before daybreak the next morning. [2]

Situated mere miles from the Illinois border and free soil, slaveholders throughout Marion county, Missouri found themselves constantly combatting escapes. But this latest episode proved “more alarming in extent.” As the Palmyra Whig attested days later, “there must have been a full and perfect understanding among these several servants,” who left the farms and residences of six different enslavers at the same time. Visions of enslaved people seizing their freedom in concert unnerved Missouri slaveholders, though most contended that the root of the problem lay not inside slaveholding households, but rather in outside agitation. Antislavery preachers and abolitionist operatives, they insisted, were responsible for the mounting number of escapes. Thus in the weeks and months following the nighttime exodus, slaveholders in Marion county mounted an aggressive campaign to “close our doors against abolition and free soil influences.” [3] Slaveholders’ frenzied efforts to clamp shut their doors triggered a months-long war of words with their Illinois neighbors and church officials, revealing how coordinated group escapes inflamed political tensions over slavery on the eve of the Civil War.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

Even before the Palmyra escape took place, slaveholders in Missouri already felt under siege in 1853, as a mounting number of “stampedes” occurred throughout the state. Back in May, a widely-circulated report from the Alton, Illinois Telegraph headlined “Slave Stampedes,” announced that “slaves are running away from Missouri, at the present time, in battalions.” It thus comes as little surprise that the term was used to describe the group flight from Palmyra mere months later. While initial reporting from the Palmyra Whig did not employ the word “stampede,” in mid-November the neighboring Hannibal Courier situated the escape within “several stampedes among the negroes” that had occurred recently. Around the same time, the Boston Herald summarized a bulletin about the episode originally published in the Chicago Tribune, affixing the new headline, “A Stampede.” As controversy over the escape escalated throughout the winter, the Quincy, Illinois Whig employed the term on multiple occasions while defending its residents from allegations of “their supposed connexion with slave stampedes from the other side of the river.” Still later in February 1854, the Palmyra Whig referred to the October escape as the “recent stampede of negroes.” [4]

MAIN NARRATIVE

Although their actions made headlines, the names of the 11 enslaved Missourians who struck out for freedom do not survive. They were claimed by six slaveholders from Palmyra and adjoining Fabius township, at the northeastern corner of Marion county. Six of the freedom seekers–a man, a woman, and four children, likely a family–fled from slaveholder Albert Gallatin Johnson’s farm some nine miles north of Palmyra. Their flight may have been motivated by their enslaver’s future plans. When he put his farm up for sale in May, Johnson had announced his intention of relocating to Texas. The family of six probably feared forced removal to the Deep South, or worse yet, being separated at the auction block. [5] Four other enslaved people, apparently all men, escaped from the Fabius township farms of slaveholders Rufus Mathews, Jeremiah K. Taylor, Caleb Taylor, and a female slaveholder identified only as Mrs. Hopkins. [6] Rounding out the group of escapees was an eleventh freedom seeker, an enslaved man who escaped from the Palmyra home of prominent slaveholding lawyer John T. Redd. [7]

Living on adjoining farms, or perhaps even members of the same extended family, these 11 enslaved people knew one another well. After what must have involved considerable planning and coordination, they slipped away on Saturday night, October 29, reaching Mendon, Illinois in the predawn hours of Sunday, October 30. Once their absence was noticed, Marion county slaveholders scrambled to action. On Monday afternoon, October 31, a large posse of white Missourians headed to Quincy in pursuit, but the freedom seekers were long since gone. Nonetheless, when the Palmyra Whig went to press on Thursday, November 3, its editors still thought it possible that the freedom seekers “may all be secured and returned to their masters.” [8]

Even as they sought to track down the runaways, slaveholding Missourians were quick to accuse white abolitionists of having masterminded the escape. The Palmyra Whig postulated that “some person or persons well acquainted with the best mode of effecting the escape of fugitives” had been involved. Residents in Fabius township singled out Quincy, Illinois, “a city containing some of the vilest abolition thieves in the Mississippi valley.” Some 20 miles to the southeast, editors of the Hannibal Courier concurred, pronouncing it “our opinion that the emissaries of negro-stealing societies are prowling about the country, exciting the slave population to insubordination, and enticing them away from their masters.” Further to the west, the Paris, Missouri Mercury agreed that the runaways must have been “assisted by white friends.” [9]

To be sure, slaveholders often blamed white activists for “enticing” enslaved people to escape, even when they had no evidence to back up those charges. Reared in proslavery logic, many white southerners imagined that enslaved people (whom they considered an inferior race) would not choose to seek out liberty on their own, or be capable of escaping without outside help. Some scholars have argued that white southerners’ obsession with antislavery “emissaries” bordered on a “conspiracy theory,” allowing slaveholders to maintain that enslaved people themselves were not resisting, and the only source of unrest originated from outside actors. But while that might hold true in the Deep South, the historian Stanley Harrold cautions that in border slave states like Missouri, concerns about antislavery activists were by no means unfounded. In 1841, to name just one example, three students from Quincy had crossed the river to Marion county in an abortive attempt to help runaways. They were captured, denounced by a Palmyra prosecutor as “notorious land pirates,” and each sentenced to lengthy spells in the Missouri State Penitentiary. Indeed, while it remains unclear if the 11 freedom seekers had help from the very outset, they likely did obtain aid from a network of abolitionists soon after crossing into Illinois. [10]

There was a well-established Underground Railroad “route” running from Quincy to Mendon, the very route the freedom seekers were known to have taken. About one mile west of Mendon was the farm of abolitionist Jireh Platt, who logged details about the escape in his diary in December 1853. Decades later in 1896, his son Jeremiah Evarts Platt revealed more about the assistance the Platt family likely gave to the Palmyra freedom seekers, writing that “eleven slaves came along at one time some of them women.” Platt recalled that he and his relatives concealed the freedom seekers under hay in “two tightly covered wagons.” It was “not practicable” to stop at Plymouth, some 30 miles to the northeast and traditionally the next place of refuge for escapees, so Platt drove for some 60 miles in the direction of Chicago, returning home a full four days later. Jeremiah believed that he was “about 17 years old” at the time of the escape described, which would place the incident in the early 1850s. Although written decades apart, together these two remarkable sources strongly suggest that the Platt family helped the Palmyra freedom seekers on their quest for liberty. [11]

Meanwhile, slaveholders Albert Johnson and Rufus Mathews offered up a sizable $3,000 reward, even telegraphing ahead to where they correctly suspected the runaways were headed–Chicago. However, the city was a center of opposition to the recently-passed 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the editors of the Chicago Tribune (a Free Soil newspaper) refused to even run the enslavers’ ad. “No one need apply,” the Tribune mocked, unless prepared to “sell his soul, for ‘thirty pieces.'” On November 16, a group of white Missourians arrived in Chicago in pursuit, distributing handbills that prominently announced the $3,000 reward. But the Chicago Tribune ridiculed them the very next day, announcing that the slaveholders were “too late.” Already about a week prior, the the 11 freedom-bound Missourians had reached Chicago, and reportedly departed for Canada. Journalists often used “Canada” as a general byword for freedom, so the freedom seekers’ final destination remains unknown. Regardless, they would not be re-enslaved, and their daring escape had succeeded. [12]

AFTERMATH

Panicked slaveholders convened at Palmyra on Monday, November 7 to form the Marion Association, a proslavery vigilance group. Declaring that “by the action of the Abolitionists, our rights and property are eminently endangered,” the Association outlined a system for a new slave patrol. For a fee of five dollars, slaveholders could join the organization, which would keep a detailed description of their human property on file, and promised to immediately pursue any freedom seekers. [13]

After several meetings in November, the Marion Association invited Thomas L. Anderson, a local Whig politician, to speak at a December 24 gathering. Before “one of the largest audiences” ever assembled in the county court house at Palmyra, Anderson invoked biblical justifications for slavery, while denouncing “fanatics” from Quincy, whom he alleged “have for some time carried on a secret intercourse with our slaves.” Anderson knew of what he spoke. In May 1848, an enslaved woman he held named Hannah Coger had escaped from his residence in Marion county and traveled through Quincy, before reaching the Platte farm in Mendon. In his diary, abolitionist Jireh Platte recorded Coger’s arrival on May 19 and her backstory–Coger had apparently been trying to purchase her freedom, and was only $100 shy of doing so before she bolted to Illinois. [14]

But now on Christmas Eve 1853, Anderson addressed the latest stampede from Marion county. A few weeks prior, he bellowed, “from twelve to fifteen thousand dollars worth of slave property has been clandestinely removed from our midst.” Almost as galling, Anderson added, was that local slaveholders had been “laughed at, ridiculed and insulted, for making legal and constitutional efforts to capture the flying refugees”–apparently referring to the Chicago Tribune‘s sardonic refusal to publish Johnson and Mathew’s reward notice, and mocking remarks about the pursuers being “too late.” Anderson, who in 1856 would be elected to represent northeastern Missouri in Congress, concluded by suggesting that local residents “suspend all business and intercourse” with their Illinois neighbors. [15]

Anderson’s fiery speech electrified his white listeners, but he was not the first proslavery Missourian to suggest severing ties with Illinois. In mid-November, the anonymous correspondent “Marion” called upon Missouri residents to resolve “neither to buy or sell to any citizen of Illinois and of Quincy in particular,” and “have no intercourse with them till they put down negro-stealing.” The Quincy Whig thundered back, unconvinced that “any citizen of Quincy had anything to do with the recent negro stampede.” Behind the volley of accusations was the reality that frequent stampedes had jarred many Missouri slaveholders into a siege mentality. “Almost every man in Northern Missouri can attest,” read a column in the Hannibal Courier, “the public mind is kept in a constant state of fermentation and nervous irritability.” Convinced that outside emissaries were behind the October stampede and similar escapes, slaveholders sought to insulate their farms, households, and human property from contact with northerners. [16]

Accordingly, slaveholders’ next order of business was to expel Rev. William Sellers, a northern Methodist minister. In 1844, the Methodist Church fractured into northern and southern wings over clashing teachings about slavery. When Sellers, a member of the northern branch who was known for his antislavery sentiments, announced that he would preach in Fabius township, local whites erupted in outrage. A committee of five–among them Caleb Taylor, one of the slaveholders impacted by the October stampede–tried to meet with Sellers and “ascertain his views upon the subject of slavery.” When Sellers demurred, a public meeting was held on February 18, 1854, at the Union School house in Fabius township. Although the presiding elder of the church, J.H. Dennis, appeared and lobbied for “religious toleration,” local slaveholders blasted the church for “their unholy crusade upon our rights,” and Sellers for attempting to “create disaffection among our slaves.” They warned that any northern Methodist “preaching or teaching in this community” would be greeted as “unfriendly to our best interests, and as a disturber of the peace.” [17]

FURTHER READING

The most detailed report of the escape was published by the Palmyra Whig on November 3. Subsequently, minutes from the Marion Association’s meetings, as well as editorials, were printed in editions of the Palmyra Whig, Hannibal Courier, and Quincy Whig. [18]

Although many members of the Marion Association, as well as local presses, readily leveled blame at white abolitionists for the escape, other members pointed the finger at free African Americans. At a January 2, 1854 meeting held at Palmyra, the Marion Association sought to clamp down on the presence of free African Americans in the state. They urged Missouri lawmakers to make it illegal to manumit a bond person, unless they were transported to the West African colony of Liberia. The Hannibal Courier reported on proceedings approvingly, imploring readers to be cognizant of the “example and corrupting influence of the free negroes that we permit to remain among us.” [19]

Benjamin Merkel’s 1943 essay “The Underground Railroad and the Missouri Borders, 1840-1860” was among the first scholarly works to mention the October 1853 escape. Merkel read Hannibal and Palmyra papers, and suggested that the freedom seekers were “probably assisted by abolitionists.” [20] More recently, Stanley Harrold’s Border War (2010) indirectly refers to the escape while reporting on Thomas Anderson’s thundering antiabolitionist speech at Palmyra. Harrold situates the proslavery gathering within the broader context of what many in the Border South perceived as “assaults on its economic, social, cultural, and racial status quo.” [21] Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018) notes the episode and the increased “vigilance” practiced by slaveholders in its wake. Blackett contends that proslavery vigilance groups, such as the Marion Association, succeeded in quelling the number of escapes from the Palmyra region. Reports of escapes from Marion county “ceased for a while,” he observes, until spiking again during the summer of 1857. [22]

[1] According to son Henry Dutton Platt, his father Jireh maintained both a a “diary & farm record” and a “blue book,” the latter which contained “vastly more” details, though its whereabouts remains unknown. Henry Platt wrote Underground Railroad historian Wilbur Siebert drawing excerpts from Jireh Platt’s diary and farm book. He said the entry for December 1853 quoted above only identified the month (December) and not the year, but it appears clear from the context that it was written in 1853. See Henry Dutton Platt, “Some Facts about the Underground Railroad in Ill.,” Wilbur H. Siebert Underground Railroad Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB].

[2] “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853.[WEB]

[3] “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853 [WEB];”Public Meeting,” Palmyra, MO Whig, February 23, 1854.

[4] “Slave Stampedes,” Alton, IL Telegraph, May 23, 1853, quoted in Boston Liberator, June 10, 1853; “Negro Stealing,” Hannibal, MO Courier, November 10, 1853; “A Stampede,” Boston Herald, November 15, 1853; “The Feeling Across the River,” Quincy, IL Whig, December 2, 1853; “Misrepresentation,” Quincy, IL Whig, December 12, 1853; “Prompt Proceedings,” Palmyra, MO Whig, February 23, 1854.

[5] “Farm For Sale,” Palmyra, MO Whig, May 26, 1853; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Fabius Township, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Fabius Township, Marion County, MO, Family 167, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]. The editors of the Palmyra Whig drew additional attention to Johnson’s advertisement, praising his land as “one of the most desirable farms in the county.” For the number of enslaved people who escaped from each slaveholder, see the original Palmyra Whig report, “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853.

[6] 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Fabius Township, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Fabius Township, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Fabius Township, Marion County, MO, Family 130, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]. The Palmyra Whig alluded that the individual enslaved by Mrs. Hopkins had been residing with a John Gwynn of neighboring Lewis county, likely meaning that they had been hired out (or rented) to Gwynn. Evidently this individual journeyed south from Lewis county on Saturday, October 29, to join the group somewhere in Fabius township.

[7] 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Palmyra, Marion County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Palmyra, Marion County, MO; 1850 U.S. Census, Palmyra, Marion County, MO, Family 320, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[8] “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853 [WEB].

[9] “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853 [WEB]; “Negro Stealing,” Hannibal, MO Courier, November 10, 1853; Paris, MO Mercury, quoted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 16, 1853; “Public Meeting,” Palmyra, MO Whig, February 23, 1854.

[10] The historian Larry Gara was among the first to argue that southern fears of an extensive Underground Railroad network stretching deep into slave territory were wildly exaggerated. See Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1961), 18, 84-87, [see post]. On the “conspiracy theory” line of thinking, see John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 274-279. For Harrold’s historiographical intervention, see Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 42, and for the July 1841 episode, 50-52, [see post]. The three abolitionist students involved in the 1841 incident (James Burr, George Thompson, Alanson Work) later authored a memoir Prison Life and Reflections: Or, A Narrative of the Arrest, Trial, Conviction, Imprisonment, Treatment, Observations, Reflections, and Deliverance of Work, Burr and Thompson… (Hartford, OH: A. Work, 1850), [WEB].

[11] Jeremiah Evarts Platt to Wilbur Siebert, March 28, 1896, Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]. Also see letters and essay from his brother, Henry Dutton Platt, also written to Siebert. Henry Dutton Platt to Wilbur Siebert, March 20, 1896, Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]; Henry Dutton Platt, “Some Facts about the Underground Railroad in Ill.,” Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB]. See post on Siebert’s work.

[12] “Clear the Track! The Train is Coming,” Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1853 [WEB]; “Too Late,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1853, quoted in Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 24, 1853; “Abolitionism in Missouri,” Chicago Tribune, November 22, 1853. Unfortunately, the Tribune‘s decision not to publish the ad (which according to the editors contained a “full description of each passenger”) means that there is no known record of the names of the 11 freedom seekers.

[13] “Abolitionism in Missouri,” St. Louis, MO Republican, November 15, 1853; Quincy, IL Whig, November 21, 1853 [WEB]

[14] “T.L. Anderson, Esq.,” Hannibal, MO Courier, December 29, 1853; Henry Dutton Platt, “Some Facts about the Underground Railroad in Ill.,” Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, [WEB].

[15] For a complete transcript of Anderson’s speech, see “Speech of Thomas L. Anderson, Esq.,” Quincy, IL Whig, February 6, 1854. Also see the entry for Anderson in the Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress. Anderson’s charge that “from twelve to fifteen thousand dollars worth of slave property has been clandestinely removed from our midst” comes from the Quincy Whig‘s February 6, 1854 transcript of the speech. Other sources (such as Stanley Harrold’s Border War) report a slightly different version, with Anderson saying that abolitionists carried “off eight or ten thousand dollars… [of human property] at a time.” This account comes from a 1943 article by Benjamin Merkel, who quoted from the Hannibal Whig Messenger of December 15, 1853 (before Anderson’s December 24 address had taken place). According to the Library of Congress, the Hannibal Whig Messenger is available on microfilm at the Hannibal Public Library and State Historical Society of Missouri. See Benjamin G. Merkel, “The Underground Railroad and the Missouri Borders, 1840-1860,” Missouri Historical Review 37:3 (April 1943): 278, [WEB]; Harrold, Border War, 162.

[16] “Non-Intercourse,” Quincy, IL Whig, November 28, 1853; “The Feeling Across the River,” Quincy, IL Whig, December 2, 1853; “Misrepresentation,” Quincy, IL Whig, December 12, 1853; “The Underground Railroad Again,” Quincy, IL Whig, December 20, 1853; Another anonymous contributor, “Fabius,” declared the Quincy Whig‘s denial to be a “lie, black and foul,” while continuing to scold Illinoisans for “stealing our property.” In its November 28 weekly edition, the Quincy Whig had reprinted the Chicago Tribune‘s mocking article, which apparently enraged the anonymous correspondent Fabius, who called it “that infamous thing.”

[17] “Prompt Proceedings,” and “Public Meeting,” Palmyra, MO Whig, February 23, 1854; History of Marion County, Missouri (St. Louis: E.F. Perkins, 1884), 1:318-320, [WEB]; Lucas P. Volkman, Houses Divided; Evangelical Schisms and the Crisis of the Union in Missouri (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 94. On Sellers, also see Minutes of the Missouri Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, held in Hannibal, Missouri, March 28th to April 2nd, 1888 (Kirksville, MO: Journal Printing House, 1888), 13, [WEB].

[18] See esp. “Runaway Negroes,” Palmyra, MO Whig, November 3, 1853, reprinted in St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 7, 1853 [WEB]; “Negro Stealing,” Hannibal, MO Courier, November 10, 1853; “Marion Association,” Hannibal, MO Courier, January 12, 1854; “Public Meeting,” Palmyra, MO Whig, February 23, 1854.

[19] “Marion Association,” Palmyra, MO Whig, January 5 1854; “Complaints of the People,” and “Marion Association,” Hannibal, MO Courier, January 12, 1854.

[20] Merkel, “The Underground Railroad and the Missouri Borders, 1840-1860,” 278.

[21] Harrold, Border War, 161-162.

[21] Richard J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 140.

Video

Escape Attributes

Outcomes

Sources

The most detailed report of the escape was published by the Palmyra Whig on November 3. Subsequently, minutes from the Marion Association’s meetings, as well as editorials, were printed in editions of the Palmyra Whig, Hannibal Courier, and Quincy Whig.

Although many members of the Marion Association, as well as local presses, readily leveled blame at white abolitionists for the escape, other members pointed the finger at free African Americans. At a January 2, 1854 meeting held at Palmyra, the Marion Association sought to clamp down on the presence of free African Americans in the state. They urged Missouri lawmakers to make it illegal to manumit a bond person, unless they were transported to the West African colony of Liberia. The Hannibal Courier reported on proceedings approvingly, imploring readers to be cognizant of the “example and corrupting influence of the free negroes that we permit to remain among us.”

Benjamin Merkel’s 1943 essay “The Underground Railroad and the Missouri Borders, 1840-1860” was among the first scholarly works to mention the October 1853 escape. Merkel read Hannibal and Palmyra papers, and suggested that the freedom seekers were “probably assisted by abolitionists.” More recently, Stanley Harrold’s Border War (2010) indirectly refers to the escape while reporting on Thomas Anderson’s thundering anti-abolitionist speech at Palmyra. Harrold situates the proslavery gathering within the broader context of what many in the Border South perceived as “assaults on its economic, social, cultural, and racial status quo.” Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018) notes the episode and the increased “vigilance” practiced by slaveholders in its wake. Blackett contends that proslavery vigilance groups, such as the Marion Association, succeeded in quelling the number of escapes from the Palmyra region. Reports of escapes from Marion county “ceased for a while,” he observes, until spiking again during the summer of 1857.