We have included 30 featured Missouri stampede-related episodes on this page, beginning with a group escape from the Daggs farm in Clark County, Missouri in 1848 that was apparently not labeled a stampede by contemporaries (the term was just in its infancy) and concluding with a newspaper-described "stampede" of formerly enslaved people trying to enlist at the USCT office in Ray County in 1863. Our naming process is simple. We list year, location and then either "escape" or "stampede" depending on how contemporaries identified the episode. Some stampedes involved as many as 50 freedom seekers; others involved much smaller groups or what appeared as connected series of escapes by individuals or families. To access full narratives and more information on the stampedes below, just click on the title links, though please note that some of these narratives are still in development.

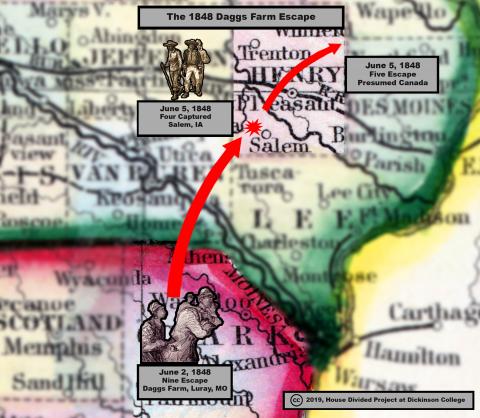

1848 Daggs Farm Escape

On Friday evening, June 2, 1848, at least nine enslaved people--John and Mary Walker, their four children, and Sam and Dorcas Fulcher, along with their pregnant daughter Julia--escaped from the Daggs Farm in Luray, Missouri. Their enslaver, Ruel J. Daggs, sent a slave-catching posse in pursuit, led by his son. At first, the runaways received help and shelter at a Quaker-dominated settlement in Salem, Iowa. The Daggs posse soon captured some of the freedom seekers and then held the town of Salem hostage for a period of time in pursuit of the rest. The townspeople of Salem refused to turn over the rest of the runaways, however. Ultimately, Daggs sued in federal court and received damages under the 1793 fugitive statute, but he never actually received the money.

On Friday evening, June 2, 1848, at least nine enslaved people--John and Mary Walker, their four children, and Sam and Dorcas Fulcher, along with their pregnant daughter Julia--escaped from the Daggs Farm in Luray, Missouri. Their enslaver, Ruel J. Daggs, sent a slave-catching posse in pursuit, led by his son. At first, the runaways received help and shelter at a Quaker-dominated settlement in Salem, Iowa. The Daggs posse soon captured some of the freedom seekers and then held the town of Salem hostage for a period of time in pursuit of the rest. The townspeople of Salem refused to turn over the rest of the runaways, however. Ultimately, Daggs sued in federal court and received damages under the 1793 fugitive statute, but he never actually received the money.

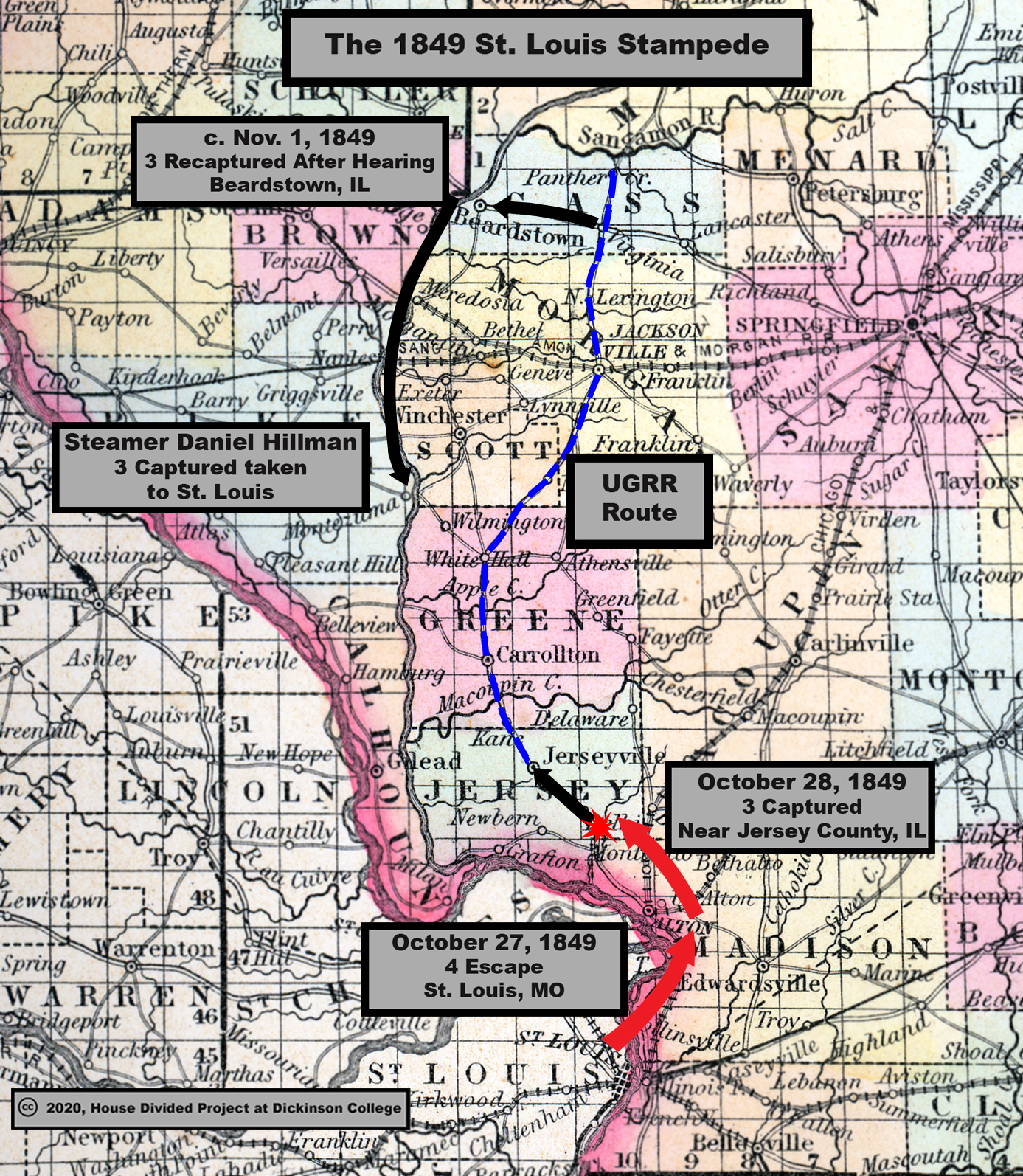

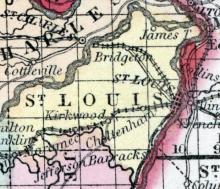

1849 St. Louis Stampede

On Saturday night, October 27, 1849, a group of six enslaved people escaped from St. Louis for "parts unknown," according to the local newspaper. The flight came in the wake of a series of recent group escapes, leading many in the city to suspect "that they have been stampeded." Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim must have mapped out their escape from slavery long before the night of Saturday, October 27, 1849. The four young men, ranging in age from 20 to 30, planned an audacious path out of St. Louis that involved assistance from African American and white abolitionists on both sides of the Missouri-Illinois border. At first, everything went according to plan. North of St. Louis, they boarded a skiff with a free black man named Bill Williams and reached Gabaret Island. There, Williams and the freedom seekers hopped aboard a second boat piloted by several white abolitionists who took them to the Illinois shore. They continued on land, tromping northward by foot for more than 20 miles–only to be recaptured within 24 hours.

On Saturday night, October 27, 1849, a group of six enslaved people escaped from St. Louis for "parts unknown," according to the local newspaper. The flight came in the wake of a series of recent group escapes, leading many in the city to suspect "that they have been stampeded." Henry, Jeff, Pell, and Tim must have mapped out their escape from slavery long before the night of Saturday, October 27, 1849. The four young men, ranging in age from 20 to 30, planned an audacious path out of St. Louis that involved assistance from African American and white abolitionists on both sides of the Missouri-Illinois border. At first, everything went according to plan. North of St. Louis, they boarded a skiff with a free black man named Bill Williams and reached Gabaret Island. There, Williams and the freedom seekers hopped aboard a second boat piloted by several white abolitionists who took them to the Illinois shore. They continued on land, tromping northward by foot for more than 20 miles–only to be recaptured within 24 hours.

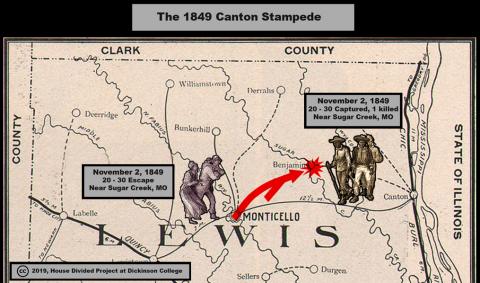

1849 Canton Stampede

In early November 1849, somewhere between 35 and 50 enslaved people around Canton in Lewis County, Missouri, led by a woman named Lin and a man known as Miller's John, planned a stampede for freedom but were betrayed and cornered before they could cross the Mississippi River. There was a violent shootout that left at least one dead and resulted in dozens of newspaper articles across the nation.

In early November 1849, somewhere between 35 and 50 enslaved people around Canton in Lewis County, Missouri, led by a woman named Lin and a man known as Miller's John, planned a stampede for freedom but were betrayed and cornered before they could cross the Mississippi River. There was a violent shootout that left at least one dead and resulted in dozens of newspaper articles across the nation.

1850 St. Louis Stampede

Up to 14 freedom seekers escaped from St. Louis and passed through Springfield, Illinois in January 1850, where they received help from Jameson Jenkins, a free black neighbor of Abraham Lincoln's.

Up to 14 freedom seekers escaped from St. Louis and passed through Springfield, Illinois in January 1850, where they received help from Jameson Jenkins, a free black neighbor of Abraham Lincoln's.

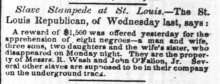

1852 St. Louis Stampede

On Tuesday, July 13, 1852, four enslaved people escaped from St. Louis: 23-year-old George (or William Johnson), who had a free wife in St. Louis, 36-year-old John, 20-year-old Henry, and 16-year-old Isaac. Their enslaver, John Mattingly, advertised a $400 reward for their recapture.

On Tuesday, July 13, 1852, four enslaved people escaped from St. Louis: 23-year-old George (or William Johnson), who had a free wife in St. Louis, 36-year-old John, 20-year-old Henry, and 16-year-old Isaac. Their enslaver, John Mattingly, advertised a $400 reward for their recapture.

1852 Ste. Genevieve Stampede

On Saturday night, September 4, 1852, eight enslaved workers from the Valle mines coordinated a stampede through Ste. Genevieve. Three of the enslaved men --Isaac, Joseph and Bill-- escaped from Valle Lead Mines in Jefferson county, some 30 miles west. Their escape was coordinated with five other freedom seekers from the town of Ste. Genevieve where the Valle family lived. These young men (all named in a runaway advertisement) included Bernard, Edmund, Henry, Joseph and Theodore. The freedom seekers from Ste. Genevieve also probably worked at the mines (at least occasionally). All eight of the men were ultimately recaptured in Illinois, in Alton and near Jerseyville.

On Saturday night, September 4, 1852, eight enslaved workers from the Valle mines coordinated a stampede through Ste. Genevieve. Three of the enslaved men --Isaac, Joseph and Bill-- escaped from Valle Lead Mines in Jefferson county, some 30 miles west. Their escape was coordinated with five other freedom seekers from the town of Ste. Genevieve where the Valle family lived. These young men (all named in a runaway advertisement) included Bernard, Edmund, Henry, Joseph and Theodore. The freedom seekers from Ste. Genevieve also probably worked at the mines (at least occasionally). All eight of the men were ultimately recaptured in Illinois, in Alton and near Jerseyville.

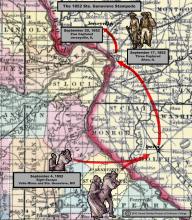

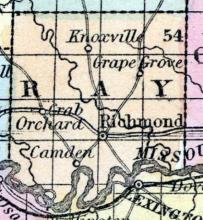

1853 Ray County Stampede

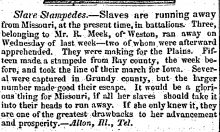

In mid-May 1853, a group of 15 enslaved people escaped in a "stampede" from Ray county, Missouri, bound for Iowa. "Several" were recaptured in Grundy county, but "the larger number" successfully escaped.

In mid-May 1853, a group of 15 enslaved people escaped in a "stampede" from Ray county, Missouri, bound for Iowa. "Several" were recaptured in Grundy county, but "the larger number" successfully escaped.

1853 Weston Stampede

Three enslaved people escaped from slaveholder R. Meek in Weston, Missouri. A report noted that the freedom seekers were "making for the Plains." However, two were later recaptured. Contemporary reports described the escape of these three bond people as part of a wave of recent "slave stampedes" unsettling the institution throughout western Missouri.

Three enslaved people escaped from slaveholder R. Meek in Weston, Missouri. A report noted that the freedom seekers were "making for the Plains." However, two were later recaptured. Contemporary reports described the escape of these three bond people as part of a wave of recent "slave stampedes" unsettling the institution throughout western Missouri.

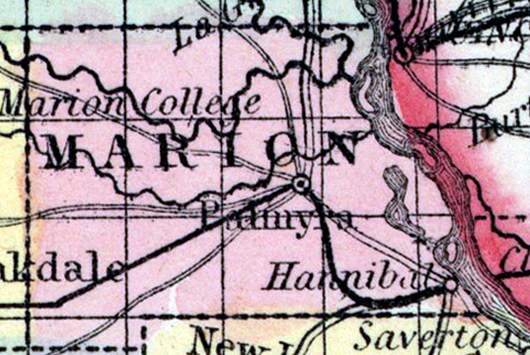

1853 Palmyra Stampede

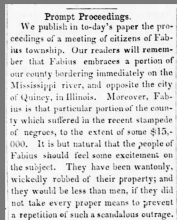

On October 29, 1853, around 11 enslaved people escaped in what was described as a "stampede" from Palmyra, Missouri. Later in February 1854, a local paper reported that over $15,000 in human "property" had been lost as a result of the enslaved Missourians' mass flight from bondage.

On October 29, 1853, around 11 enslaved people escaped in what was described as a "stampede" from Palmyra, Missouri. Later in February 1854, a local paper reported that over $15,000 in human "property" had been lost as a result of the enslaved Missourians' mass flight from bondage.

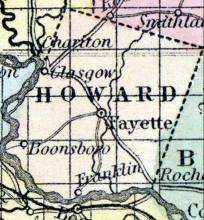

1854 Howard County Stampede

A report from the LaGrange, MO Bulletin noted that sometime in early July 1854, four enslaved people escaped from Howard county, and were recaptured near LaGrange. Slaveholders blamed this escape on abolitionists from Quincy. The newspaper in Quincy responded by commenting: "We are getting a little tired of this disposition of our Missouri friends to lose their equilibrium, and charge that every slave stampede that takes place originates in this city."

A report from the LaGrange, MO Bulletin noted that sometime in early July 1854, four enslaved people escaped from Howard county, and were recaptured near LaGrange. Slaveholders blamed this escape on abolitionists from Quincy. The newspaper in Quincy responded by commenting: "We are getting a little tired of this disposition of our Missouri friends to lose their equilibrium, and charge that every slave stampede that takes place originates in this city."

1854 Lewis County Stampede

A report from the LaGrange, MO Bulletin detailed the escape of four more enslaved people from Lewis County, who were not identified by name, and accused "the sympathetic Abolitionists of Quincy" of "enticing" the bond people away. The Quincy Whig responded by ruminating that their Missouri neighbors "charge that every slave stampede that takes place originates in this city." According to reports, the group's escape was successful.

A report from the LaGrange, MO Bulletin detailed the escape of four more enslaved people from Lewis County, who were not identified by name, and accused "the sympathetic Abolitionists of Quincy" of "enticing" the bond people away. The Quincy Whig responded by ruminating that their Missouri neighbors "charge that every slave stampede that takes place originates in this city." According to reports, the group's escape was successful.

1854 St. Louis Stampedes (October)

On Sunday night, October 22, 1854, a group of 15-20 enslaved Missourians escaped from St. Louis via boat and disembarked at Keokuk, Iowa, making their way across Wisconsin and reportedly to Canada. A month later, another large group escaped from the city and also liberated themselves. By December 1854, there was a sense of crisis among St. Louis slaveholders over "slave stampedes" and what they perceived as the escalating challenges to their tyranny over the enslaved.

On Sunday night, October 22, 1854, a group of 15-20 enslaved Missourians escaped from St. Louis via boat and disembarked at Keokuk, Iowa, making their way across Wisconsin and reportedly to Canada. A month later, another large group escaped from the city and also liberated themselves. By December 1854, there was a sense of crisis among St. Louis slaveholders over "slave stampedes" and what they perceived as the escalating challenges to their tyranny over the enslaved.

1854 St. Louis Stampedes (November)

On Friday night, November 24, 1854, ten enslaved people escaped from St. Louis. Their names were Lunsford Johnson, 26 years old, Emily (or Adeline), aged roughly 20 years, and her three children, 4-year-old Ellen, 2-and-a-half-year-old Belle, and one-year-old Edmund. They were joined by a 26-year-old man named Spencer, a 27-year-old man named David and perhaps three others. They reached Chicago at the same time as four freedom seekers from St. Charles and three more from Ste. Genevieve, apparently all moving together as part of a second stampede through St. Louis in just over a month. The furor prompted one of the slaveholders (Richard Berry) to race to Chicago and convince federal authorities to recapture his runaways. The botched rendition effort on December 8, 1854 led to no arrests and compelled Missouri newspapers to blast the "nullification" of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.

On Friday night, November 24, 1854, ten enslaved people escaped from St. Louis. Their names were Lunsford Johnson, 26 years old, Emily (or Adeline), aged roughly 20 years, and her three children, 4-year-old Ellen, 2-and-a-half-year-old Belle, and one-year-old Edmund. They were joined by a 26-year-old man named Spencer, a 27-year-old man named David and perhaps three others. They reached Chicago at the same time as four freedom seekers from St. Charles and three more from Ste. Genevieve, apparently all moving together as part of a second stampede through St. Louis in just over a month. The furor prompted one of the slaveholders (Richard Berry) to race to Chicago and convince federal authorities to recapture his runaways. The botched rendition effort on December 8, 1854 led to no arrests and compelled Missouri newspapers to blast the "nullification" of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.

1855 St. Louis Stampede

On Sunday evening, May 21, 1855, around eight enslaved Missourians escaped via boat from St. Louis, with the aid of Mary Meachum, a prominent free African American in the city. However, authorities were waiting on the opposite shore, and five of the escapees were recaptured. Meachum and two other free blacks were later charged with assisting the escapees to flee.

On Sunday evening, May 21, 1855, around eight enslaved Missourians escaped via boat from St. Louis, with the aid of Mary Meachum, a prominent free African American in the city. However, authorities were waiting on the opposite shore, and five of the escapees were recaptured. Meachum and two other free blacks were later charged with assisting the escapees to flee.

1856 St. Louis Stampede

Around July 10, 1856, three enslaved people escaped from the residence of prominent St. Louis citizen John O'Fallon. Apparently never recaptured, their escape may have been linked to the flight of eight enslaved people from slaveholder Robert Wash just days later. On Monday night, July 14, 1856, an enslaved family--a husband and wife, their three sons, two daughters and the wife's sister, escaped from slaveholder Robert Wash near St. Louis. None of the eleven were reported to have been recaptured.

Around July 10, 1856, three enslaved people escaped from the residence of prominent St. Louis citizen John O'Fallon. Apparently never recaptured, their escape may have been linked to the flight of eight enslaved people from slaveholder Robert Wash just days later. On Monday night, July 14, 1856, an enslaved family--a husband and wife, their three sons, two daughters and the wife's sister, escaped from slaveholder Robert Wash near St. Louis. None of the eleven were reported to have been recaptured.

1856 Hannibal Stampede

On Sunday night, October 19, 1856, a free African American preacher named Isaac McDaniel rescued from slavery his wife, Mary, their five-year-old son Daniel, and another family enslaved by Hannibal slaveholder John Bush: 32-year-old Anthony, his wife, 34-year-old Eliza, and their children, eight-year-old Margaret and six-year-old Lewis. Taking Bush's horse and carriage, McDaniel led the two families of freedom seekers out of slavery. While the fate of the group is unknown, the nearby Palmyra paper ruminated that "doubtless the whole party have made good their escape."

On Sunday night, October 19, 1856, a free African American preacher named Isaac McDaniel rescued from slavery his wife, Mary, their five-year-old son Daniel, and another family enslaved by Hannibal slaveholder John Bush: 32-year-old Anthony, his wife, 34-year-old Eliza, and their children, eight-year-old Margaret and six-year-old Lewis. Taking Bush's horse and carriage, McDaniel led the two families of freedom seekers out of slavery. While the fate of the group is unknown, the nearby Palmyra paper ruminated that "doubtless the whole party have made good their escape."

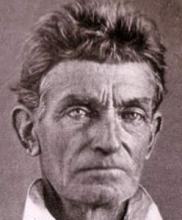

1858 Vernon County Stampede

On December 20, 1858, abolitionist John Brown and a group of armed activists led a raid into Vernon county, Missouri, at the behest of enslaved Missourian Jim Daniels who was owned by James Lawrence. The raid freed Daniels, his family and several other enslaved people, 11 in total (12 following the birth of John Brown Daniels), escaping westward through Kansas.

On December 20, 1858, abolitionist John Brown and a group of armed activists led a raid into Vernon county, Missouri, at the behest of enslaved Missourian Jim Daniels who was owned by James Lawrence. The raid freed Daniels, his family and several other enslaved people, 11 in total (12 following the birth of John Brown Daniels), escaping westward through Kansas.

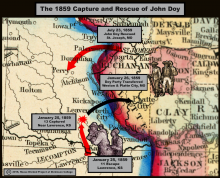

1859 Kansas Stampede and Doy Rescue

On January 25, 1859, abolitionist John Doy, two free African Americans Wilson Hays and Charles Smith, attempted to lead 11 freedom seekers from various locations across western Missouri to freedom in Iowa. They were recaptured near Lawrence, Kansas. Doy was later rescued from prison to great fanfare, while Smith and one of the freedom seekers, Bill Riley, also managed to escape Missouri authorities. The others, however, were not so fortunate, and apparently sold down to the Deep South.

On January 25, 1859, abolitionist John Doy, two free African Americans Wilson Hays and Charles Smith, attempted to lead 11 freedom seekers from various locations across western Missouri to freedom in Iowa. They were recaptured near Lawrence, Kansas. Doy was later rescued from prison to great fanfare, while Smith and one of the freedom seekers, Bill Riley, also managed to escape Missouri authorities. The others, however, were not so fortunate, and apparently sold down to the Deep South.

1859 Western Missouri Stampede

Sometime in October 1859, a group of 26 enslaved people escaped from western Missouri, and were guided by an antislavery operative through Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois, through Chicago and finally to Detroit.

Sometime in October 1859, a group of 26 enslaved people escaped from western Missouri, and were guided by an antislavery operative through Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois, through Chicago and finally to Detroit.

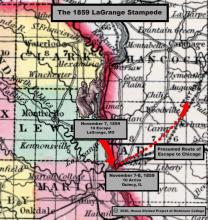

1859 LaGrange Stampede

On Monday night, November 7, 1859, ten enslaved people crowded into a stolen flatboat and pushed off into the Mississippi River. Escaping from bondage in the riverside town of LaGrange, Missouri, these five men and five women steered a course by moonlight, local knowledge, and sheer determination, traveling some ten miles southeast to Quincy, Illinois. The next morning, seven slaveholders awoke to discover their “valuable slaves,” worth “not less than $10,000,” suddenly gone, and offered up a hefty $2,650 reward for their recapture. Costly as it was to local slaveholders, it was by no means the first such large escape launched from the vicinity. The town’s newspaper, the LaGrange American, hardly needed to remind readers that this latest episode marked “the third or fourth successful stampede that has taken place from LaGrange in the past three or four months.” Escapes were becoming so common, the paper alleged that “there is a regular underground railroad established from this place to Chicago.”

On Monday night, November 7, 1859, ten enslaved people crowded into a stolen flatboat and pushed off into the Mississippi River. Escaping from bondage in the riverside town of LaGrange, Missouri, these five men and five women steered a course by moonlight, local knowledge, and sheer determination, traveling some ten miles southeast to Quincy, Illinois. The next morning, seven slaveholders awoke to discover their “valuable slaves,” worth “not less than $10,000,” suddenly gone, and offered up a hefty $2,650 reward for their recapture. Costly as it was to local slaveholders, it was by no means the first such large escape launched from the vicinity. The town’s newspaper, the LaGrange American, hardly needed to remind readers that this latest episode marked “the third or fourth successful stampede that has taken place from LaGrange in the past three or four months.” Escapes were becoming so common, the paper alleged that “there is a regular underground railroad established from this place to Chicago.”

1860 Bredell Farm Stampede

In late August 1860, five enslaved people, a mother, two sons, a daughter and a young child "closely related to them," escaped from slaveholder Edward Bredell's property about six miles outside of St. Louis along the Clayton road. Bredell "was on a visit to the East," and the family of five left under the pretense of visiting nearby African Americans, and used the opportunity to escape.

In late August 1860, five enslaved people, a mother, two sons, a daughter and a young child "closely related to them," escaped from slaveholder Edward Bredell's property about six miles outside of St. Louis along the Clayton road. Bredell "was on a visit to the East," and the family of five left under the pretense of visiting nearby African Americans, and used the opportunity to escape.

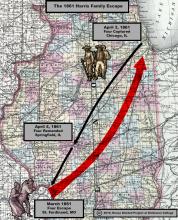

1861 Chicago IL Stampede

Sometime in March 1861, a family of four--"Onesimus" Harris, his wife Ann and children George and Charles--escaped from St. Ferdinand township, on the northern outskirts of St. Louis. The family was recaptured by U.S. officers in April 1861, and remanded by U.S. Commissioner Stephen Corneau to bondage. The arrest of the Harris family set off what Chicago newspapers described as a "stampede" of other runaway slaves and free black residents in Chicago.

Sometime in March 1861, a family of four--"Onesimus" Harris, his wife Ann and children George and Charles--escaped from St. Ferdinand township, on the northern outskirts of St. Louis. The family was recaptured by U.S. officers in April 1861, and remanded by U.S. Commissioner Stephen Corneau to bondage. The arrest of the Harris family set off what Chicago newspapers described as a "stampede" of other runaway slaves and free black residents in Chicago.

1861 Springfield MO Stampede

On November 8, 1861, more than 150 enslaved Missourians escaped into the camp of Brig. Gen. Joseph H. Lane's Kansas Brigade. Although Lane allowed slaveholders to search his camp, a reporter for the New York Herald attested that not a single freedom seeker had been recaptured. The 150 freedom seekers from new Springfield and others from elsewhere in western Missouri followed Lane's brigade back into Kansas, arriving on free soil on November 13.

On November 8, 1861, more than 150 enslaved Missourians escaped into the camp of Brig. Gen. Joseph H. Lane's Kansas Brigade. Although Lane allowed slaveholders to search his camp, a reporter for the New York Herald attested that not a single freedom seeker had been recaptured. The 150 freedom seekers from new Springfield and others from elsewhere in western Missouri followed Lane's brigade back into Kansas, arriving on free soil on November 13.

1862 St. Joseph Stampede

In late January and early February 1862, there were a series of escapes totaling seven people from St. Joseph and dubbed a "stampede" by a local newspaper after it reported mocking coverage of the episode from a Leavenworth, Kansas newspaper. Two enslaved people, Dan and Sina, escaped from Rev. M.E. Lard near St. Joseph, Missouri. Their enslaver, Lard, offered a $200 reward for their recapture. An enslaved girl named Fanny, aged 14-15, escaped from Col. Howard, who offered a $100 reward for Fanny's re-enslavement. Four enslaved men––Jason, Charles, Peter, and Shelby––escaped from the farms of slaveholders Pullin, Elder, and Stamper near St. Joseph. The three enslavers advertised a joint reward of $500 for the recapture of the four escapees. According to a report in the Leavenworth, KS Times, the four men reached safety in the neighboring state. The Kansas newspaper noted that people were gossiping that one of the enslavers was Fanny's father.

In late January and early February 1862, there were a series of escapes totaling seven people from St. Joseph and dubbed a "stampede" by a local newspaper after it reported mocking coverage of the episode from a Leavenworth, Kansas newspaper. Two enslaved people, Dan and Sina, escaped from Rev. M.E. Lard near St. Joseph, Missouri. Their enslaver, Lard, offered a $200 reward for their recapture. An enslaved girl named Fanny, aged 14-15, escaped from Col. Howard, who offered a $100 reward for Fanny's re-enslavement. Four enslaved men––Jason, Charles, Peter, and Shelby––escaped from the farms of slaveholders Pullin, Elder, and Stamper near St. Joseph. The three enslavers advertised a joint reward of $500 for the recapture of the four escapees. According to a report in the Leavenworth, KS Times, the four men reached safety in the neighboring state. The Kansas newspaper noted that people were gossiping that one of the enslavers was Fanny's father.

1862 Ste. Genevieve Stampedes

Multiple reports citing a Ste. Genevieve newspaper noted a "stampede of negroes" from throughout Ste. Genevieve county during the fall of 1862.

Multiple reports citing a Ste. Genevieve newspaper noted a "stampede of negroes" from throughout Ste. Genevieve county during the fall of 1862.

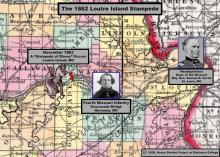

1862 Loutre Island Stampede

In November 1862, Union soldiers guarding a vital bridge crossing at Hermann, Missouri opened their lines to allow “a stampede of slaves” from nearby Loutre Island to pass through. Once behind Union lines, the group of enslaved Missourians believed they had finally realized their hard-won freedom. So did the Union soldiers who greeted them, however curtly. The officer on duty, Capt. Bathasar Mundwiller of the Fourth Missouri Infantry, was short on rations and had “no work for them,” so he ordered the freedom seekers out of his camp, assuring them they could find work throughout Union-controlled Gasconade county, where “no one could interfere with them.” An initial dispatch fired off by a local citizen to Union authorities reported that “a stampede of slaves had taken place from beyond the river.” Subsequently his letter, including its mention of a “stampede,” was reprinted in the St. Louis Missouri Democrat, the New York-based National Anti-Slavery Standard and Douglass’ Monthly. The same letter also served as the basis for a brief report about the same “stampede of slaves” published by the New York Tribune in early December. President Abraham Lincoln may well have perused one of those many press reports. Just weeks later in January 1863, Lincoln privately told two Republican senators that “the negroes were stampeding in Missouri.” Whether or not Lincoln had specifically called to mind the Loutre Island escape, the episode was part of the growing tide of “stampedes” in late 1862 that informed the president’s strategy to push for compensated emancipation in Missouri.

In November 1862, Union soldiers guarding a vital bridge crossing at Hermann, Missouri opened their lines to allow “a stampede of slaves” from nearby Loutre Island to pass through. Once behind Union lines, the group of enslaved Missourians believed they had finally realized their hard-won freedom. So did the Union soldiers who greeted them, however curtly. The officer on duty, Capt. Bathasar Mundwiller of the Fourth Missouri Infantry, was short on rations and had “no work for them,” so he ordered the freedom seekers out of his camp, assuring them they could find work throughout Union-controlled Gasconade county, where “no one could interfere with them.” An initial dispatch fired off by a local citizen to Union authorities reported that “a stampede of slaves had taken place from beyond the river.” Subsequently his letter, including its mention of a “stampede,” was reprinted in the St. Louis Missouri Democrat, the New York-based National Anti-Slavery Standard and Douglass’ Monthly. The same letter also served as the basis for a brief report about the same “stampede of slaves” published by the New York Tribune in early December. President Abraham Lincoln may well have perused one of those many press reports. Just weeks later in January 1863, Lincoln privately told two Republican senators that “the negroes were stampeding in Missouri.” Whether or not Lincoln had specifically called to mind the Loutre Island escape, the episode was part of the growing tide of “stampedes” in late 1862 that informed the president’s strategy to push for compensated emancipation in Missouri.

1863 Chiles Farm Stampede

Around Sunday, November 29, 1862, three enslaved men escaped from the farm of Col. Chiles, near Lexington, Missouri, taking with them "three horses and a wagon and left for Kansas." The Lexington Union reported their escape as part of a wave of "negro stampeding" during the winter of 1863. The three men were reportedly halted by U.S. authorities and placed "in the U.S. service."

Around Sunday, November 29, 1862, three enslaved men escaped from the farm of Col. Chiles, near Lexington, Missouri, taking with them "three horses and a wagon and left for Kansas." The Lexington Union reported their escape as part of a wave of "negro stampeding" during the winter of 1863. The three men were reportedly halted by U.S. authorities and placed "in the U.S. service."

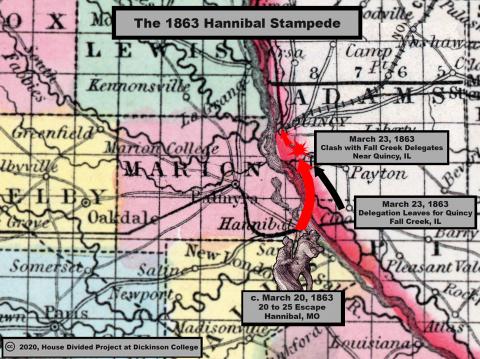

1863 Hannibal Stampede

On Monday, March 23, 1863, Wash Minter and around 20 to 25 other freedom seekers who fled slavery in a “stampede” from Hannibal, Missouri, were plodding their way towards Quincy, Illinois. Having successfully crossed the Mississippi River and already traversed several miles through southern Illinois, on the rain-soaked, “almost impassable” road to Quincy, the large group of runaways ran head first into a delegation of fiercely anti-black Democrats from the neighboring town of Fall Creek, Illinois. As it happened, this contingent of white “farmers and workingmen” were bound for a countywide Democratic meeting in Quincy, where later that evening they would pronounce themselves in favor of preserving the Union, but emphatically “opposed to a war for the freedom of the negro.”

On Monday, March 23, 1863, Wash Minter and around 20 to 25 other freedom seekers who fled slavery in a “stampede” from Hannibal, Missouri, were plodding their way towards Quincy, Illinois. Having successfully crossed the Mississippi River and already traversed several miles through southern Illinois, on the rain-soaked, “almost impassable” road to Quincy, the large group of runaways ran head first into a delegation of fiercely anti-black Democrats from the neighboring town of Fall Creek, Illinois. As it happened, this contingent of white “farmers and workingmen” were bound for a countywide Democratic meeting in Quincy, where later that evening they would pronounce themselves in favor of preserving the Union, but emphatically “opposed to a war for the freedom of the negro.”

1863 St. Louis Stampede

On Saturday night, April 11, 1863, three enslaved people, Jerry, Louis, and Nathan, escaped from slaveholder Olly Williams's farm on the St. Charles Rock road outside St. Louis. The three freedom seekers left in Williams's wagon, guided by two mules and packed full with "other property" of their slaveholder.

1863 Lafayette County Stampede

On Friday night, April 24, 1863, a group of around 50 enslaved Missourians escaped from Lafayette county, Missouri, bringing with them six wagons, 18 horses and a carriage. Lexington papers reported that the group was among the "not less than three hundred slaves" who had escaped from the county over the preceding three weeks. "These slaves all go to Kansas," a report added.

On Friday night, April 24, 1863, a group of around 50 enslaved Missourians escaped from Lafayette county, Missouri, bringing with them six wagons, 18 horses and a carriage. Lexington papers reported that the group was among the "not less than three hundred slaves" who had escaped from the county over the preceding three weeks. "These slaves all go to Kansas," a report added.

1863 Platte County Stampede

According to Kansas City newspapers, in August 1863, there was "a perfect stampede" of enslaved families in Platte County. The accounts estimated that "the negroes are leaving at the rate of thirty or forty a day, and only a few hundred remain." "The same process is going on all along the border," claimed a report that was soon reprinted in the St. Louis Missouri Democrat, "and Missouri will soon be rid of her slaves, in fact, if not in name." The journalist blamed all of this on the "Emancipation Ordinance" because Blacks in Missouri (who were exempt from the proclamation) "cannot draw nice distinctions." The conclusion was especially telling: "The barriers which fence in the slave systems in this State are crumbling daily, and while our politicians are talking the negro is quietly acting without any reference to statue books or ordinance." Another newspaper account from St. Joseph, Missouri, specifically identified Platte County sheriff W.T. "Wash" Woods as the source for the information on the high rate of escaping slaves.

According to Kansas City newspapers, in August 1863, there was "a perfect stampede" of enslaved families in Platte County. The accounts estimated that "the negroes are leaving at the rate of thirty or forty a day, and only a few hundred remain." "The same process is going on all along the border," claimed a report that was soon reprinted in the St. Louis Missouri Democrat, "and Missouri will soon be rid of her slaves, in fact, if not in name." The journalist blamed all of this on the "Emancipation Ordinance" because Blacks in Missouri (who were exempt from the proclamation) "cannot draw nice distinctions." The conclusion was especially telling: "The barriers which fence in the slave systems in this State are crumbling daily, and while our politicians are talking the negro is quietly acting without any reference to statue books or ordinance." Another newspaper account from St. Joseph, Missouri, specifically identified Platte County sheriff W.T. "Wash" Woods as the source for the information on the high rate of escaping slaves.

1863 Ray County Stampede

In Ray county, Missouri, thirty enslaved people formed a "stampede" to the U.S. recruiting offices and enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops.

In Ray county, Missouri, thirty enslaved people formed a "stampede" to the U.S. recruiting offices and enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops.