Participants

Route

Description

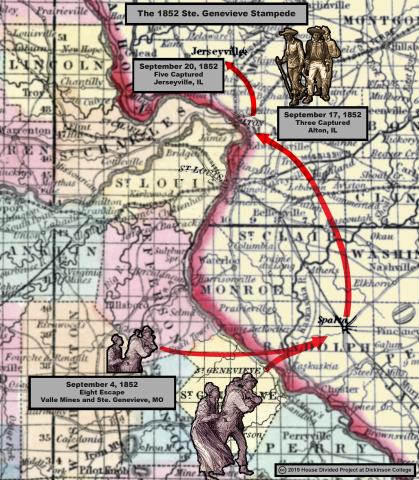

On Saturday night, September 4, 1852, eight enslaved workers from the Valle mines coordinated a stampede through Ste. Genevieve. Three of the enslaved men --Isaac, Joseph and Bill-- escaped from Valle Lead Mines in Jefferson county, some 30 miles west. Their escape was coordinated with five other freedom seekers from the town of Ste. Genevieve where the Valle family lived. These young men (all named in a runaway advertisement) included Bernard, Edmund, Henry, Joseph and Theodore. The freedom seekers from Ste. Genevieve also probably worked at the mines (at least occasionally). All eight of the men were ultimately recaptured in Illinois, in Alton and near Jerseyville.

Full Narrative

To view this full narrative with all of its embedded multi-media, please go to the 1852 Ste. Genevieve Stampede post at our research blog. For a printable version, download this PDF.

DATELINE: STE. GENEVIEVE, SEPTEMBER 4, 1852

On the night of September 4, 1852, two groups of freedom seekers set out from eastern Missouri. Apparently coordinating their escapes, a group of five men named Bernard, Edmund, Henry, Joseph and Theodore left the riverside town of Ste. Genevieve. At the same time, three others –Isaac, Joseph and William (or “Bill”)– departed from the Valle Lead Mines, located some thirty miles to the west in adjacent Jefferson County, Missouri. Joining together along the way, the eight enslaved men, ranging in age from 18 to 40 and equipped with firearms, crossed the Mississippi River, heading straight for the town of Sparta, Illinois, widely reputed as a haven for freedom seekers. Although a group of Missourians were soon in hot pursuit, one Illinois editor doubted they would succeed. The freedom seekers, he noted, were all “young men,” who would be difficult to track down and recapture. [1]

Yet it was not Missourians who ultimately foiled the eight men’s quest for freedom, but rather a handful of southern Illinois residents who responded to the tempting $1,600 reward offered for their return. Word of the “Ste. Genevieve fugitives” spread fast throughout southern Illinois, so much so that when three of the freedom seekers (Bernard, Joseph and Theodore) ventured into Alton, Illinois in search of food on or around September 17, they were promptly seized by a trio of local residents. The remaining five freedom seekers lingered in the area, but the pangs of hunger drove them to search for food as well. On September 20, while looking for provisions near Jerseyville, Illinois, some 20 miles north of Alton, one of the escaped bondsmen encountered a local named Ely B. Way, who offered to “assist them” and invited them to his house for a meal. However, Way and his neighbor –William A. Scott, a justice of the peace for nearby Delhi, Illinois– had other plans in mind. Way managed to secure the freedom seekers’ weapons, and once the five men were ensconced within his home, he captured them. According to one news report, “Scott, armed with a gun, and Way with a knife, re-entered and frightened them into an immediate surrender.” The Ste. Genevieve “stampede” for freedom thus came to an abrupt and cruel end. [2]

STAMPEDES CONTEXT

Although often overlooked, the Ste. Genevieve stampede is featured in Richard Blackett’s recent book, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018). Blackett opens his chapter on Missouri and Illinois with a description of the September 1852 escape, using the case to highlight what he considers to be the frequency and significance of group escapes from that area. The recurring group escapes along the Missouri-Illinois border, Blackett writes, generated considerable angst and consternation among Missouri slaveholders, as they seemed to reveal “a level of planning and coordination” among enslaved people that was especially worrisome in the eyes of slaveholders. [3]

Multiple newspapers at the time labeled the group escape as a stampede. The St. Louis-based Missouri Republican not only ran an ad offering a hefty reward for the freedom seekers’ return, but also took the additional step of drawing its readers attention to the offer with the news item entitled: “Negro Stampede–Large Reward.” [4] Across the border in Illinois, the Alton Weekly Telegraph reported on the case under the headline “Slave Stampede.” [5] In the meantime, other papers throughout the region churned out reports about the case, with at least two serials–the Louisville, Kentucky Daily Courier, and the Wheeling, Virginia Daily Intelligencer–referring to the escape as a “slave stampede.” [6]

MAIN NARRATIVE

The eight enslaved men who launched the Ste. Genevieve stampede in September 1852 were claimed by six different slaveholders, though all were connected by virtue of being “hired out” (or rented) by their slaveholders to work at Valle Lead Mines, situated along the southern border of Jefferson County, Missouri. The owners of the mines, the Valle family, had wielded influence in the region for some time, tracing their lineage back to a French colonial officer who served as commandant of Ste. Genevieve during the mid-1700s. The family also had a lengthy relationship with slavery, with enslaved labor recorded at Valle-owned lead mines in the area as early as 1757. The Valle Mines near Ste. Genevieve opened during the mid-1820s and quickly became lucrative, churning out an average of 1,500 tons of lead per year. [7] By 1852, the mines were under the principal ownership of Felix Valle, a 52-year-old Ste. Genevieve native. Two of his nephews, 39-year-old Amadee Valle, a prominent lawyer in St. Louis, and 34-year-old Neree Valle, a merchant based in St. Louis, were also involved with the family mining operation. [8]

However, only three of the freedom seekers who escaped in September 1852 (Isaac, Joseph and Theodore) were actually held by members of the Valle family. Felix Valle, who still resided in Ste. Genevieve, held Isaac, in his mid-30s, and the younger Joseph of the group, aged about 22-24, while Neree Valle laid claim to 25-year-old Theodore. Most (if not all) of the other escapees were evidently hired out (or “rented”) to work at the Valle Lead Mines. [9]

Those other freedom seekers included 26-year-old Bernard and 18-year-old Henry, who were claimed by local pro-slavery politician Lewis V. Bogy, then a candidate for a Missouri congressional seat; Edmund, among the oldest of the group at roughly 37-40 years of age, who was held by William Skewes, an English emigrant who served as superintendent of the Valle Mines; William, or “Bill,” about 23 years old, who was claimed by Jonathan Smith, a slaveholder who resided near Valle Mines; and the older Joseph, around 27 at the time of the escape, who was held by Antoine Janis, a Ste. Genevieve slaveholder who laid claim to 13 other enslaved people. [10]

Although it remains unclear if any of the eight men were related to one another, most had likely grown up around the Ste. Genevieve area, among slaveholding families with Francophone roots. At least six of the eight freedom seekers were fluent in both English and French. Yet however they came to know one another, whether through longstanding family ties or after being hired out at the Valle Mines, by the evening of September 4, 1852 these eight enslaved men had joined forces for their daring escape plot. That night, William, Isaac and the younger Joseph–the three men then at the Valle Mines–headed east, linking up with the other five freedom seekers who set off from the vicinity of Ste. Genevieve. [11]

Crossing the Mississippi River, the eight men made for Sparta, Illinois, where they hoped to find local anti-slavery activists. However, despite its reputation as a refuge for runaway slaves, a party of Spartan residents reportedly attempted to seize the group of freedom seekers, though the eight men were able to escape into the woods outside of town. They continued northward, perhaps in search of the rural black community of Rocky Fork, another well known haven for escaped bondsmen. Whether they ever reached Rocky Fork remains unclear. In the two weeks following their escape from Ste. Genevieve, the freedom seekers journeyed as far north as Alton, Illinois, located just across the river from St. Louis. [12]

Meanwhile, back in St. Louis, Amadee Valle received the unwelcome news that eight enslaved men working at his family’s highly profitable Jefferson County lead mines had “run off.” On September 9, Valle headed to the city’s police office, where at his behest Lt. Charles W. Woodward and five St. Louis police officers were dispatched to recapture the fugitive slaves. It was likely also Amadee Valle who passed on word of the escape to two of the city’s most widely circulated papers. On September 10, the St. Louis News informed its readers of the escape, while the affected slaveholders took out an ad in the Missouri Republican, which first appeared on September 11, offering a staggering $1,600 reward for recapture of the eight freedom seekers. Four days later, the Valles placed another ad in the paper, dropping slaveholders Antoine Janis and Jonathan Smith from the signatories on the reward, which was reduced to $750. This time, the Valles offered a prediction of the freedom seekers’ likely route: “It is supposed they will make for Chicago by way of Sparta, Illinois.” [13]

Woodward and his five Missouri policemen failed to catch up with freedom seekers, who continued north, arriving in the neighborhood of Alton, Illinois. However, after nearly two weeks on the run, the group was in desperate need of food. Hoping to find provisions, three of the freedom seekers, Bernard, the younger Joseph and Theodore, entered Alton on or around September 17. However, three Alton residents who had apparently learned of the reward quickly seized the men. The captors, named Lane, Meld and Moore, were described by the St. Louis Missouri Republican as “citizens of Alton,” though one of the men may have been a local constable. A man named William C. Moore served as justice of the peace in neighboring Brighton, Illinois (some 12 miles distant from Alton), though it remains unclear if he was the same Moore involved in the case. [14] On September 18, Lane, Meld and Moore brought the three freedom seekers to St. Louis, where they were placed in the St. Louis County jail. While an Alton newspaper wondered aloud “what proportion will be awarded for this partial capture,” the remaining five freedom seekers–Edmund, Henry, Isaac, the older Joseph and William–decided not to take their chances, and headed some twenty miles farther north, reaching the vicinity of Jerseyville, Illinois. Still in need of provisions, one of the men ventured out, reaching the home of Ely B. Way near Jerseyville. Way, a 28-year-old laborer, was then hosting his neighbor, 29-year-old William A. Scott, justice of the peace in the nearby town of Delhi. When the freedom seeker tried to order food for himself and four others, Way and Scott “instantly suspected” that this man was one of the “Ste. Genevieve fugitives.” [15]

Eager for the reward, Way and Scott quickly retired to another room, “to consult on the best means of apprehending them.” While both men hailed from free states–Way from either Indiana or Ohio, and Scott from Illinois–Scott’s parents were both born in slaveholding states (his father in Tennessee, and his mother in Missouri). Together, they crafted a plan to seize the fugitives and claim the hefty reward for themselves. When they emerged, Way duplicitously “told the negro to go after his companions and they could all have a meal at his house,” and even promised to “assist them to escape.” While the freedom seeker went to relay the message to his four compatriots, who were concealed in a woods nearby, the “preparation for supper commenced” at the Way house. In setting their trap, Way and Scott took extra precautions, “removing from the room every chair, stick, &c. which could be used as a weapon.” [16]

When the five freedom seekers showed up at the Way house, Way managed to get hold of their firearms, still acting the part of a sympathetic farmer. No sooner had the five disarmed fugitives entered the dining room than Justice Scott charged in, brandishing a gun, and together with Way, who suddenly produced a knife, demanded their “immediate surrender.” Ensnared in a well laid trap, the freedom seekers were in no position to resist. [17]

Likely traveling by wagon overnight to Alton, on the morning of September 21, Way, Scott and the five captured freedom seekers boarded the steamer Altona, bound for St. Louis. The roughly hour-long journey down the Mississippi from Alton to St. Louis must have been agonizing for Edmund, Henry, Isaac, Joseph and William, who faced grim prospects as recaptured runaways. Arriving in St. Louis, the five men were quickly handed over to local authorities, where they were reunited with Bernard, the younger Joseph and Theodore in a Missouri prison cell. While a St. Louis paper triumphantly announced the capture of “the remainder of the batch of nine negroes who ran away from Ste. Genevieve county,” Way and Scott collected their reward, which according to an Alton paper totaled $1,000. [18]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

After their recapture and confinement in the St. Louis County prison, the eight freedom seekers disappear from the historical record. While three of the men claimed that they were actually from St. Louis, their contention fell on deaf ears. “We suppose they are all from the mines,” confidently asserted the Missouri Republican. [19] More likely than not, most (if not all) of the eight freedom seekers were sold for their part in the widely publicized stampede.

The enslaved men held by Felix Valle, Isaac and the younger Joseph, were among those who may have been sold following the escape. While Valle still held five enslaved people in 1860, none match the ages of Isaac and Joseph. Shortly before his death in 1877, Valle bequeathed sums of $300 to three freed people, named Basil, Jabette and Madeline, “formerly slaves owned by me.” Isaac and Joseph, however, were not mentioned. [20] Valle’s home in Ste. Genevieve, where he likely held the two freedom seekers, was later preserved as a Missouri State Historic Site.

His nephew, the St. Louis lawyer Amadee Valle, continued to wield influence over the coming decades. As the sectional conflict intensified, Amadee emerged as a border state Republican, elected in 1860 to represent St. Louis’s Fourth Ward on the city council. A firm supporter of the Union War effort, he was listed among an “executive committee of gentlemen” helping to plan the St. Louis-based Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair in 1864. Although a member of the Missouri state legislature during the war, Valle apparently never publicly articulated his thoughts on slavery and emancipation, and was not present at the state constitutional convention which abolished slavery in January 1865. Yet he remained influential in Republican circles for years to come. During the 1870s, a Republican operative informed then-President Ulysses S. Grant that Valle “is well calculated to speak for the old French people” of Missouri. Valle was a prominent resident of St. Louis until his death in 1890. [21]

For Lewis Bogy, the slaveholder who claimed Bernard and Henry, 1852 was a doubly frustrating year. The Ste. Genevieve stampede had occurred during the midst of a hotly contested congressional election that pitted Bogy against longtime Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton. Ironically, just months before the stampede, Bogy had delivered a speech blasting Benton for opposing the Compromise of 1850 and for seeking to amend the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which Bogy claimed “has healed the dissension existing throughout the United States.” Bogy narrowly lost the election, but was later elected to the U.S. Senate, serving from 1873 until his death in 1877. [22]

FURTHER READING

The St. Louis Missouri Republican (Genealogy Bank) ran the first ad offering a reward for the eight freedom seekers, and also termed the escape a “negro stampede.” The Alton Weekly Telegraph (Newspapers.com) reported on the case throughout September 1852, including detailed articles surrounding the separate captures of the freedom seekers in Alton and near Jerseyville.

The Ste. Genevieve escape has not received much attention in recent scholarship, until Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, which profiles the escape, although without referring to it as a stampede.

[1] “Sixteen Hundred Dollars Reward!!” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852; “Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 15, 1852; “Slave Stampede” Alton, IL Weekly Telegraph, September 17, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852.

[2] “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852; “Fugitive Slave,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; “Slaves Run Off,” St. Louis News, September 10, 1852, quoted in New York Tribune, September 21, 1852; St. Louis Republican, September 19, 1852, quoted in “Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” Wilmington, NC Tri-Weekly Commercial, September 30, 1852; Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory, for 1858 and 1859, (Chicago: George W. Hawes, 1859), 339, [WEB]; Richard J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 137-139.

[3] Blackett, The Captive’s Quest, 137-140, 234, 393.

[4] “Negro Stampede–Large Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852.

[5] “Slave Stampede,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 17, 1852.

[6] “Slave Stampede,” Louisville Daily Courier, September 20, 1852; “Slave Stampede,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, September 30, 1852.

[7] Walter B. Stevens, St. Louis: History of the Fourth City, 1763-1909, (Chicago: S.J. Clarke, 1909), 661, [WEB]; Mary Louise Dalton, “Notes on the Genealogy of the Valle Family,” Missouri Historical Society Collections 2:7 (October 1906): 78, [WEB]; R.V. Kennedy, Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory, for the Year 1857, (St. Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 224, [WEB]; R.A. Campbell, Campbell’s Gazetteer of Missouri, (St. Louis: R.A. Campbell, 1875), 499, [WEB]; History of Southeast Missouri, (Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1888), 204, [WEB]; Valle Mining Company Records, Finding Aid, State Historical Society of Missouri, [WEB]; Carl J. Ekberg, Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier, (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), 150; “Ste. Genevieve, Jean Baptiste Valle House for sale,” Flat River, MO Daily Journal, November 16, 2002.

[8] Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, for 1852, (St. Louis: Missouri Republican Office, 1852), 263, [WEB]; R.V. Kennedy, Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory, for the Year 1857, (St. Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 224, [WEB]; Bonnie Stepenoff, From French Community to Missouri Town: Ste. Genevieve in the Nineteenth Century, (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 38; Paul Beckwith, Creoles of St. Louis, (St. Louis: Nixon-Jones, 1893), 18, [WEB]; Laws of the State of Missouri, Passed at the Regular Session of the 21st General Assembly, (Jefferson City, MO: W.G. Cheeney, 1861), 58, [WEB]; Dalton, “Notes on the Genealogy of the Valle Family,” 65, [WEB]; 1850 U.S. Census, Ste. Genevieve Township, Ste. Genevieve County, MO, Family 71, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, 4th Ward, St. Louis, MO, Family 674, Ancestry.

[9] “Sixteen Hundred Dollars Reward!!” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852; “Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 15, 1852; “Slaves Run Off,” St. Louis News, September 10, 1852, quoted in New York Tribune, September 21, 1852; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ward 2, St. Louis, MO, Ancestry; “Death of Amadee Valle–History of His Life,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 30, 1890.

[10] “Sixteen Hundred Dollars Reward!!” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 42, Jefferson County, MO, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Beauvais, Ste. Genevieve, MO, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Ste. Genevieve Township, Ste. Genevieve County, Missouri, Family 307, Ancestry; L.U. Reavis, Saint Louis: The Future Great City of the World, (St. Louis: C.R. Barns, 1876), 425-426, [WEB]; “Died,” Ste. Genevieve Fair Play, June 17, 1893.

[11] “Sixteen Hundred Dollars Reward!!” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852.

[12] “Slaves Run Off,” St. Louis News, September 10, 1852, quoted in New York Tribune, September 21, 1852; Blackett, The Captive’s Quest, 137-140, 152.

[13] “Sixteen Hundred Dollars Reward!!” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 11, 1852; “Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 15, 1852; “Slaves Run Off,” St. Louis News, September 10, 1852, quoted in New York Tribune, September 21, 1852; Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, for 1852, 283, [WEB].

[14] St. Louis Republican, September 19, 1852, quoted in “Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” Wilmington, NC Tri-Weekly Commercial, September 30, 1852; “Fugitive Slave,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; “Fugitive Slaves,” New Orleans Crescent, September 27, 1852; Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory, for 1858 and 1859, 335, [WEB]; Blackett, The Captive’s Quest, 137-139.

[15] St. Louis Republican, September 19, 1852, quoted in “Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” Wilmington, NC Tri-Weekly Commercial, September 30, 1852; “Fugitive Slave,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory, for 1858 and 1859, 339, [WEB];History of Greene and Jersey Counties, Illinois, (Springfield, IL: Continental Historical Company, 1885), 336, [WEB]; “Scott’s Hotel,” Alton Telegraph, September 22, 1848; 1850 U.S. Census, Township 7, Jersey County, Illinois, Families 46 and 170, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Jerseyville, Jersey County, Illinois, Family 102, Ancestry; 1880 U.S. Census, Piasa Township, Jersey County, Illinois, Family 248, Ancestry; 1855 Illinois State Census, Township 7, Jersey County, Ancestry; William A. Scott, Find A Grave, [WEB].

[16] “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852; Way’s place of birth was listed as Ohio in the 1850 Census, but Indiana in the 1860 Census. See 1850 U.S. Census, Township 7, Jersey County, Illinois, Family 46, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Jerseyville, Jersey County, Illinois, Family 102, Ancestry. For Scott’s parentage, see 1880 U.S. Census, Piasa Township, Jersey County, Illinois, Family 248, Ancestry.

[17] “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852.

[18] E.W. Gould, Fifty Years on the Mississippi; or Gould’s History of River Navigation, (St. Louis: Nixon-Jones, 1889), 674, [WEB]; “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852; “Arrest of the Other Ste. Genevieve Fugitive Slaves,” Alton Weekly Telegraph, September 24, 1852.

[19] “Five Fugitive Slaves Arrested,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 22, 1852.

[20] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ste. Genevieve, Ste. Genevieve County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Valle Township, Jefferson County, MO, Ancestry; Felix Valle, Last Will and Testament, April 5, 1877, Missouri, Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]; Also see the slave schedule for Antoine Janis, who owned 18 slaves in 1860. See 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Saline Township, Ste. Genevieve County, Ancestry.

[21] “Fourth Ward Free Democratic Meeting at Gamble Market Square,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, July 25, 1860; Announcement of the Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair, john D. McKown Papers, State Historical Society of Missouri, [WEB]; The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives, Printed During the First Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress, 1863-’64, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 110, [WEB]; The New Constitution of the State of Missouri, (St. Louis: McKee, Fishback and Company, 1865), [WEB]; Chauncey I. Filley to Ulysses S. Grant, October 25-26,1875, in John Y. Simon (ed.), The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 26:359; “Death of Amadee Valle–History of His Life,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 30, 1890; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[22] Reavis, Saint Louis, 425-432; Speech of Col. Lewis V. Bogy, the Democratic Nominee for Congress, in the First District, (St. Louis: St. Louis Times Office, 1852), 10, [WEB].

Video

Escape Attributes

Outcomes

Sources

The St. Louis Missouri Republican (Genealogy Bank) ran the first ad offering a reward for the eight freedom seekers, and also termed the escape a “negro stampede.” The Alton Weekly Telegraph (Newspapers.com) reported on the case throughout September 1852, including detailed articles surrounding the separate captures of the freedom seekers in Alton and near Jerseyville. The Ste. Genevieve escape has not received much attention in recent scholarship, until Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom, which profiles the escape, (p. 137). Blackett also wrote about the stampede in his earlier journal article, "Dispossessing Massa: Fugitive Slaves and the Politics of

Slavery After 1850," American Nineteenth Century History 10 (June 2009): 119-36.