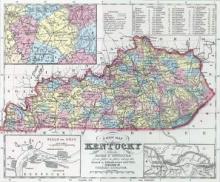

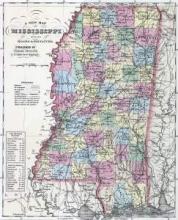

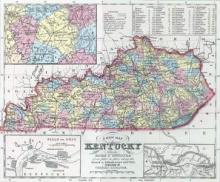

During the first few weeks of October, a Kentucky slaveholder claimed to some reporters that "a change seems to have come over the spirit of the negroes’ dreams in the Southern counties of that State, and large numbers of them are running off." The slaveholder then provided a specific illustration of his claim. "He says that over one hundred and fifty have escaped from one county, and the trouble is increasing."

View All Stampedes, 1847-1865 // 1840s // 1850s // 1860s

Displaying 201 - 212 of 212

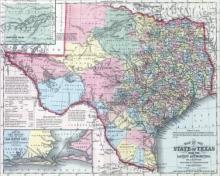

In early October 1863, newspapers claimed that the "black stampede" was getting "worse and worse in the South." "Slaves have begun to skedaddle from Texas to Mexico."

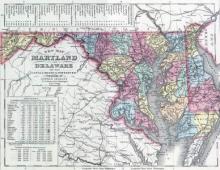

Around Sunday or Monday, October 11-12, 1863, there was a "stampede of slaves" in Port Tobacco, Maryland that received attention as far away as Charleston, South Carolina. The local newspaper originally reported that there was "an exodus of forty or fifty from the neighborhood of Pomonket," adding glumly, "At this rate our county is likely to be entirely drained of available working labor in a very short time."

On Saturday night, October 17, about 50 enslaved men escaped from near Leonardtown, Maryland. It marked the latest in a series of mass escapes that had rocked Maryland slaveholders to their core. The editors of the St. Mary's Beacon connected the escape to the US army's growing efforts to recruit enslaved Marylanders.

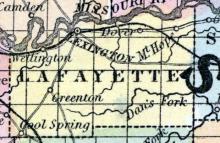

Around Sunday, November 29, 1863, three enslaved men escaped from the farm of Col. Chiles, near Lexington, Missouri, taking with them "three horses and a wagon and left for Kansas." The Lexington Union reported their escape as part of a wave of "negro stampeding" during the winter of 1863-1864. The three men were reportedly halted by U.S. authorities and placed "in the U.S. service."

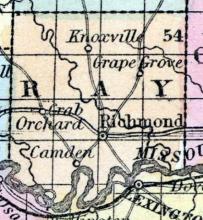

In Ray county, Missouri, thirty enslaved people formed a "stampede" to the U.S. recruiting offices and enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops.

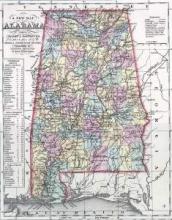

In early February, about 150 freedom seekers from around Huntsville, Alabama passed through Stevenson in the northern part of the state on their way toward Nashville, Tennessee.

In May 1864, various newspapers began reporting on the influx of enslaved families at military recruiting centers across Kentucky. One Cincinnati newspaper wrote: "Within a few days the negroes of Kentucky have become impressed with the idea that the road to freedom lies through military service, and there has been a stampede from the farms to the recruiting offices." By April 1865, the Louisville Journal was writing that "Hundreds and thousands of negroes

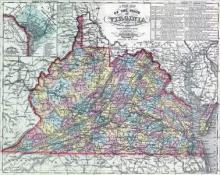

Near the end of December 1864, there was a rush of freedom seekers from Richmond, Virginia toward Union lines near the city. Richmond newspapers reported on the flight and attributed it to rumors that enslaved Black men were about to be impressed into the Confederate army. The Sentinel wrote: "A regular panic and stampede has taken place among the negroes of this city.

In early January 1865, Confederate-controlled Montgomery, Alabama experienced a disturbance involving some enslaved Black males who clashed with local authorities. According to newspaper reports, local police stumbled onto a crowd of Blacks who had taken over a "grog shop" and thereby provoked "a general stampede." Police managed to arrest "five lusty descendants of Ham," whom they identified as Pero (slaveholder Ousby), Sandy (slaveholder Ashley), Joel (slaveholder Pric

Following the adoption of a Confederate conscription law to enroll Black men into their army in March 1865, there were reports of several stampedes by enslaved families in various places to avoid service. The New York Herald reported on one such stampede in southern Mississippi in mid-April 1865, writing: "It is said that the attempt on the part of the rebels to carry out the law of their Congress requiring the negro to fight for the enslavement of his race has

On July 4, 1865, according to Gen. John M. Palmer, the Union commander in charge of Kentucky, the enslaved families of the state expected to be set free. Since slavery was still legal in the state (and would remain so until the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December), this created great anxiety among white residents. So General Palmer decided to issue passes to Blacks allowing them to seek employment in Ohio or elsewhere.