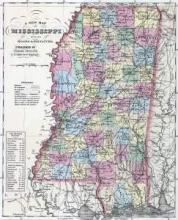

Sometimes in early January 1860, newspapers reported that a "large stampede of negroes" had attempted unsuccessfully to flee from Cherokee lands in Indian Territory toward Mexico, before they were betrayed by "a faithful negro" and recaptured.

View All Stampedes, 1847-1865 // 1840s // 1850s // 1860s

Displaying 1 - 50 of 54

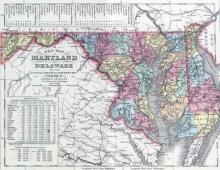

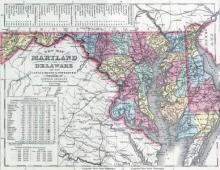

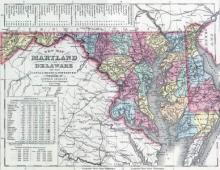

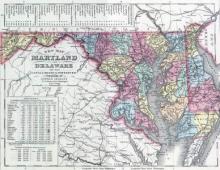

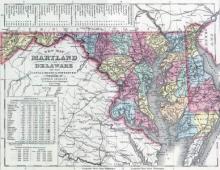

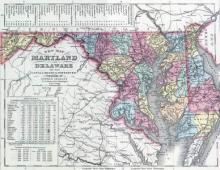

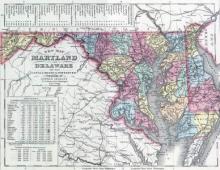

On Monday, May 28, 1860, "some eight or ten slaves," according to newspaper reports, "absconded in a body" and thus conducted a "stampede" out of Frederick, Maryland. These enslaved and unnamed individuals belonged to several slaveholders, including women Caroline E. Brengle and Mary Hammond, as well as men named John Smith, Ezra Hock, and Christian Thomas.

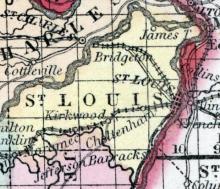

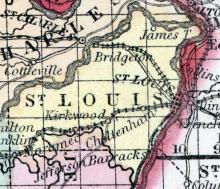

In late August 1860, five enslaved people, a mother, two sons, a daughter and a young child "closely related to them," escaped from slaveholder Edward Bredell's property about six miles outside of St. Louis along the Clayton road. Bredell "was on a visit to the East," and the family of five left under the pretense of visiting nearby African Americans, and used the opportunity to escape.

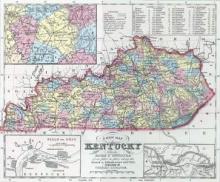

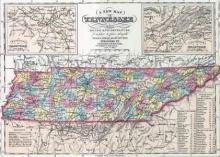

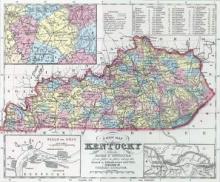

On Saturday night, September 22, 1860, there was "Quite a stampede" in Fleming Kentucky, involving at least four freedom seekers. The local newspaper mocked these runaways as "would be Free Soilers," but named most them: Jake (owned by Thomas R.

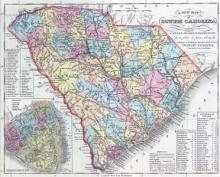

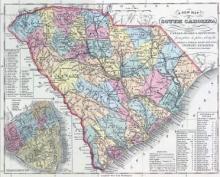

In November 1860, a widely reprinted newspaper article described the fight of free blacks in South Carolina as a "stampede." The article was referring to Black families departing the state after the passage of a new law restricting free blacks.

In early February 1860, Cleveland newspapers reported on alleged stampedes of fugitive slaves from the city heading toward Canada.

In early February 1861, newspapers described how a fugitive slave case in Cleveland scared former runaways in Toledo, Ohio to "stampede" toward Canada.

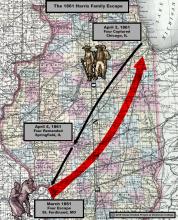

Sometime in March 1861, a family of four--"Onesimus" Harris, his wife Ann and children George and Charles--escaped from St. Ferdinand township, on the northern outskirts of St. Louis. The family was recaptured by U.S. officers in April 1861, and remanded by U.S. Commissioner Stephen Corneau to bondage. The arrest of the Harris family set off what Chicago newspapers described as a "stampede" of other runaway slaves and free black residents in Chicago.

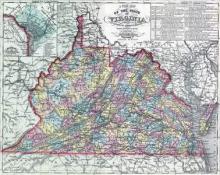

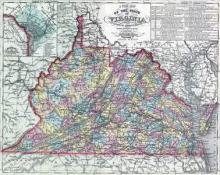

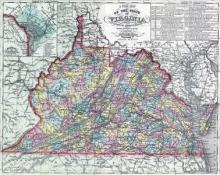

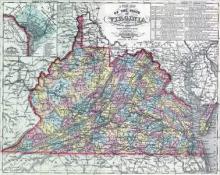

Near the end of April 1861, a correspondent for the New York Herald reported from Harrisburg that there had been an "attack" by a Marylander slaveholder across the border into southern Pennsylvania occasioned by the "stampede" of enslaved families from Maryland over the previous month. "Reliable accounts say that whole families are crossing into Adams, York, and Franklin counties," read the "midnight" dispatch, estimating that upwards of 500 had fled "since

In early June, a newspaper reported that over one hundred Virginia freedom seekers had arrived in Harrisburg, PA.

On September 16, 1861, a group of 14 runaways from the estate of Commodore Jones in Lewinsville made it to Washington, DC.

In October 1861, multiple newspapers describe "several stampedes of slaves" from Worcester County, Maryland. One Northern correspondent noted, "The negroes begin to understand that they can make hay while the sun shines, and are running away as fast as their legs can carry them."

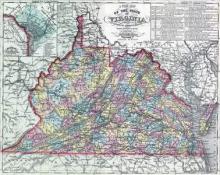

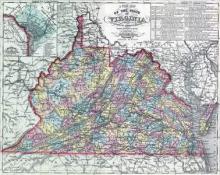

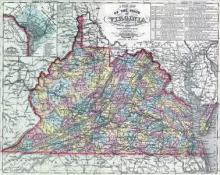

On Sunday night, November 3, 1861, there was a mass escape "of a party of some forty negroes or more" from several different slaveholders around White Point in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Newspapers in the state blamed "military authorities" for not doing more to protect slave property.

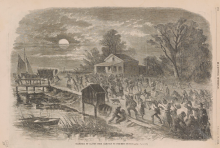

On November 8, 1861, more than 150 enslaved Missourians escaped into the camp of Brig. Gen. Joseph H. Lane's Kansas Brigade. Although Lane allowed slaveholders to search his camp, a reporter for the New York Herald attested that not a single freedom seeker had been recaptured. The 150 freedom seekers from new Springfield and others from elsewhere in western Missouri followed Lane's brigade back into Kansas, arriving on free soil on November 13.

Around December 10, 1861, about 18 freedom seekers were apprehended trying to escape from the Norfolk area to Union-controlled Fort Monroe. According to newspaper reports, "The negroes were gathered here preparatory to embarking for Fortress Monroe in a row-boat, the oars of which were carefully muffled, so as to pass our fortifications on the river without arresting the attention of the guards." The same reports claimed that the runaways were "each armed with a Colt's revolver an

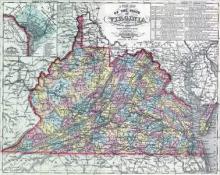

In early 1862, a Richmond newspaper warned that the Union invasion of Accomac and Northampton counties along the Delmarva peninsula had provoked "An almost general stampede of slaves on the eastern shore."

In early February 1862, a Richmond newspaper reported there had been "a stampede of negroes from the vicinity of Chuckatuck" in Isle of Wright County --which was not far from Union-occupied positions around Hampton, Norfolk and Fort Monroe on the Virginia peninsula. The newspaper used the story of the stampedes to underscore the need for drafting more local white men into the militia, claiming that the stampede "has made the necessity of these drafts even more apparent than before."

In February 1862, between thirty to forty enslaved Missourians escaped from the eastern Missouri counties of Boone, Callaway, St. Charles, and Montgomery. The St. Louis Republican reported on this "stampede of slaves," adding that city police had already been apprised of the names and descriptions of the freedom seekers.

Around June 19, 1862, a reported 150 freedom seekers crossed the northern shore of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia. A Boston newspaper reported, "They are going, going, and will soon be gone. What do secession orators say now? Why don’t they make speeches, delineating the beauties, glories, and excellence of secession? Where is the immovable foundation on which African slavery is based?"

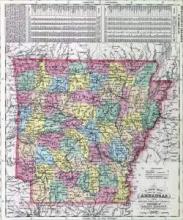

In mid-June, the Cecil Whig, a leading eastern Maryland newspaper, shared a brief, but very provocative report from Arkansas. "A slave revolt and stampede is anticipated in Crittenden county, Arkansas, opposite Memphis," claimed the Whig, "and many of the white are fleeing to Memphis for safety." There was no other information provided.

In late July 1862, the Richmond Examiner reported under the headline, "YANKEE DEPREDATIONS IN EASTERN NORTH CAROLINA," that during the previous month, there had been several mass escapes and outbreaks of violence. "The stampede of negroes from Eastern North Carolina is so great," claimed that newspaper, "that unless strong guerrilla parties are immediately formed and sent thither, it is thought that the country will be entirely drained of its slave population in a sho

A group of six to seven enslaved people (all but one of whom were men) escaped from farms near Ghent, Kentucky on horseback on Friday night, July 11, 1862. Three miles east of Madison, Indiana, the freedom seekers left their horses to cross the Ohio river by skiff. Two local Black men by the surname of Harris guided the freedom seekers, until slave catchers overtook them around 9pm on Saturday night, July 12.

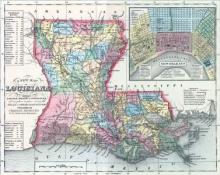

The New Orleans Delta reported that early in the morning on Monday, August 4, 1862, policemen in their city battled with a group of 25 or 30 runaway slaves along St. Ferdinand Street.

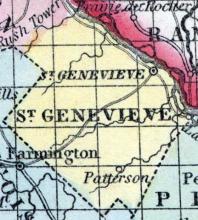

Multiple reports citing a Ste. Genevieve newspaper noted a "stampede of negroes" from throughout Ste. Genevieve county during the fall of 1862.

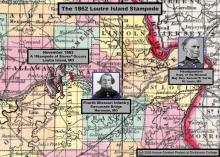

In November 1862, a group of enslaved people escaped from Loutre Island and escaped across the Missouri river into Hermann, and made their way behind Union lines. Slaveholders managed to re-arrest four of the freedom seekers, who were later freed by Union authorities.

According to the war correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, there was a "stampede" that began around New Year's Eve in 1862 with " hundreds of negroes are nightly lessening the slave power of those few counties of Eastern Virginia" where he was then stationed with the Army of the Potomac. The reporter claimed that "At least two-fifths of the slaves escaped when our army was here last year, and about one-half of the remainder were sold to the far South, immediately aft

In February 1863, a correspondent of the New York Times traveling with Gen. McPherson's 17th Corps in Louisiana during Grant's Vicksburg campaign reported encountering hundreds of runaway slaves. The Massachusetts newspaper which excerpted his account in mid-March, then labeled it "a complete stampede of negroes, old and young, from the Bayou Macon region," and claimed that "the remaining slaves are a source of more anxiety to the rebels than even the Yankees."

In late March 1863, Wash Minter and 20-25 enslaved Missourians escaped from Hannibal, Missouri into Quincy, Illinois.

On Saturday night, April 11, 1863, three enslaved people, Jerry, Louis, and Nathan, escaped from slaveholder Olly Williams's farm on the St. Charles Rock road outside St. Louis. The three freedom seekers left in Williams's wagon, guided by two mules and packed full with "other property" of their slaveholder.

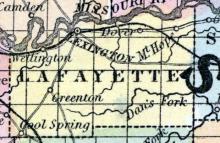

On Friday night, April 24, 1863, a group of around 50 enslaved Missourians escaped from Lafayette county, Missouri, bringing with them six wagons, 18 horses and a carriage. Lexington papers reported that the group was among the "not less than three hundred slaves" who had escaped from the county over the preceding three weeks. "These slaves all go to Kansas," a report added.

Around the beginning of June 1863, a correspondent for the New York Herald reported from Walnut Hills, near Vicksburg, that "Hundreds of negroes stampeded at the approach of our troops, and followed them into our lines."

In early June, newspaper reports claimed 60 freedom seekers had fled from multiple slaveholders in Annapolis, Maryland in what they termed "a wholesale stampede." Some of the named slaveholders included Charles Hammond, William Anderson Randolph, and Abraham Woodward. Newspapers reported that the runaways were "supposed to have gone to Washington, D.C."

In early September, the Knoxville Register reported on "a large number of slaves" who had "absconded from different parts of this country our own neighborhood contributing to some extent, to the exodus." The newspaper glumly concluded: "At the rate at which this thing has been going on for some time past, our country must soon be drained of this species of population." A Milwaukee newspaper reprinted this story along with the tale of the simultaneous stampede of enslaved

In mid September 1863, there were reports that earlier in the month there had been a number of stampeding slaves from around Pikesville, Maryland. One newspaper noted, "there seems to be a general exodus of them in that portion of the county," adding, "If this state of things continue, and it undoubtedly will, in short time there will not be an able bodied slave in that section of the country."

On Monday, September 7, 1863, a reported group of 50 enslaved people "undertook a stampede" from slaveholders in both Anne Arundel and Calvert counties, Maryland. The group was reportedly heading toward Washington until they were cornered by a local slave patrol. According to newspaper accounts, "The inferior quality of the stampeders' fire-arms enabled the citizens to capture them after having wounded a number."

On Sunday, September 13, 1863, there were reports that at least 15 enslaved African Americans, including "men, women, and children," from Cedar Point Neck in Charles county, Maryland had escaped. According to the news account, which was reprinted nationally, the group stole "a large flat-bottomed boat" from a barn, "which they carried to the creek, and thus made their escape." A Port Tobacco, Maryland newspaper reported that "not less than fifty negroes from this v

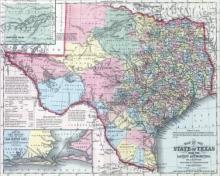

In early October 1863, newspapers claimed that the "black stampede" was getting "worse and worse in the South." "Slaves have begun to skedaddle from Texas to Mexico."

During the first few weeks of October, a Kentucky slaveholder claimed to some reporters that "a change seems to have come over the spirit of the negroes’ dreams in the Southern counties of that State, and large numbers of them are running off." The slaveholder then provided a specific illustration of his claim. "He says that over one hundred and fifty have escaped from one county, and the trouble is increasing."

Around Sunday or Monday, October 11-12, 1863, there was a "stampede of slaves" in Port Tobacco, Maryland that received attention as far away as Charleston, South Carolina. The local newspaper originally reported that there was "an exodus of forty or fifty from the neighborhood of Pomonket," adding glumly, "At this rate our county is likely to be entirely drained of available working labor in a very short time."

On Saturday night, October 17, about 50 enslaved men escaped from near Leonardtown, Maryland. It marked the latest in a series of mass escapes that had rocked Maryland slaveholders to their core. The editors of the St. Mary's Beacon connected the escape to the US army's growing efforts to recruit enslaved Marylanders.

Around Sunday, November 29, 1863, three enslaved men escaped from the farm of Col. Chiles, near Lexington, Missouri, taking with them "three horses and a wagon and left for Kansas." The Lexington Union reported their escape as part of a wave of "negro stampeding" during the winter of 1863-1864. The three men were reportedly halted by U.S. authorities and placed "in the U.S. service."

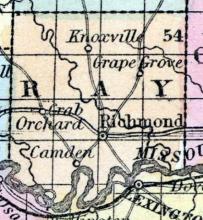

In Ray county, Missouri, thirty enslaved people formed a "stampede" to the U.S. recruiting offices and enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops.

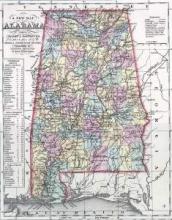

In early February, about 150 freedom seekers from around Huntsville, Alabama passed through Stevenson in the northern part of the state on their way toward Nashville, Tennessee.

In May 1864, various newspapers began reporting on the influx of enslaved families at military recruiting centers across Kentucky. One Cincinnati newspaper wrote: "Within a few days the negroes of Kentucky have become impressed with the idea that the road to freedom lies through military service, and there has been a stampede from the farms to the recruiting offices." By April 1865, the Louisville Journal was writing that "Hundreds and thousands of negroes