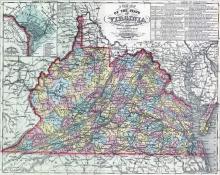

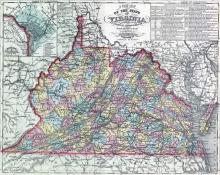

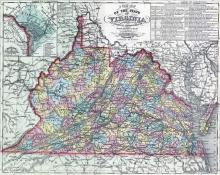

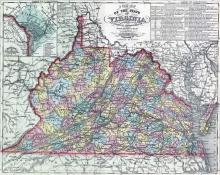

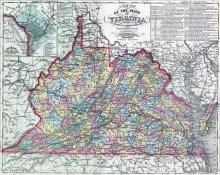

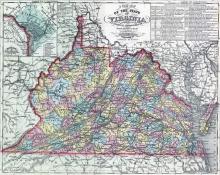

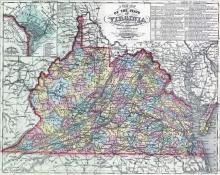

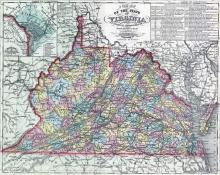

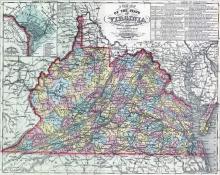

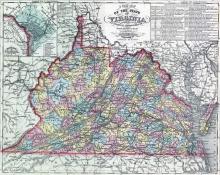

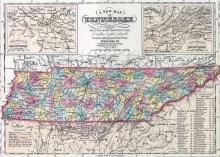

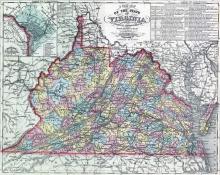

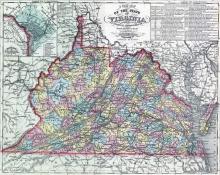

On Saturday night, September 30, 1854, around six enslaved people escaped on horseback from Pendleton county, Virginia. Some were claimed by slaveholder and general James Boggs, a resident of Pendleton county. The freedom seekers' fate remains unknown.

View All Stampedes, 1847-1865 // 1840s // 1850s // 1860s

Displaying 51 - 100 of 138

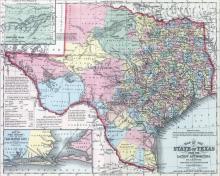

Throughout the fall of 1854, reports emerged detailing "the stampede" of enslaved Texans headed south to Mexico. They were purportedly "tempted thither by wandering tribes of women, wandering about like gypsies."

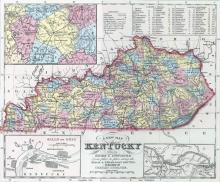

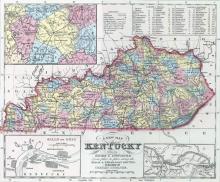

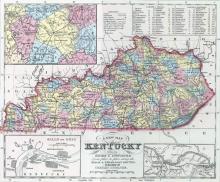

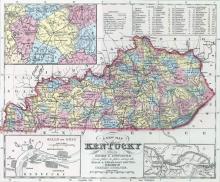

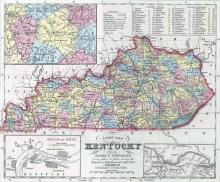

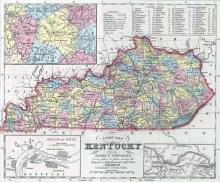

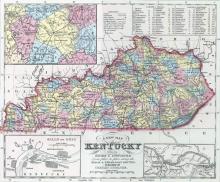

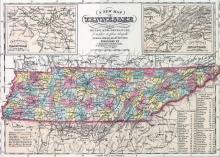

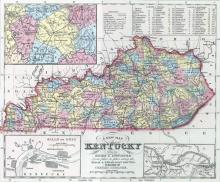

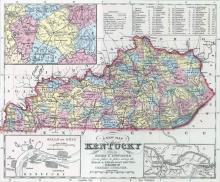

On Saturday night, October 21, 1854, "another stampede" occurred from Bourbon county, Kentucky, in which around 15 enslaved people took flight. One freedom seeker was subsequently captured near Fairview, Kentucky, and two others were sighted, but not recaptured, days later near Mays Lick. The fate of the remaining freedom seekers remains unknown.

On Sunday night, October 22, 1854, a group of 15-20 enslaved Missourians escaped from St. Louis via boat and disembarked at Keokuk, Iowa, making their way across Wisconsin and reportedly to Canada. A month later, another large group escaped from the city and also liberated themselves. By December 1854, there was a sense of crisis among St. Louis slaveholders over "slave stampedes" and what they perceived as the escalating challenges to their tyranny over the enslaved.

On Friday night, November 24, 1854, ten enslaved people escaped from St. Louis. Their names were Lunsford Johnson, 26 years old, Emily (or Adeline), aged roughly 20 years, and her three children, 4-year-old Ellen, 2-and-a-half-year-old Belle, and one-year-old Edmund. They were joined by a 26-year-old man named Spencer, a 27-year-old man named David and perhaps three others. They reached Chicago at the same time as four freedom seekers from St. Charles and three more from Ste.

On Sunday evening, November 26, 1854, eight enslaved people--five men and three women--escaped from bondage in Bourbon county, Kentucky. Crossing the Ohio river aboard two skiffs, they reportedly passed through Cincinnati en route for Canada. Their enslaver, James Hatfield, pursued them to Cincinnati on Tuesday, November 28, but returned to Kentucky after learning that the freedom seekers were long since gone.

On Saturday night, January 27, 1855, a "serious stampede" rocked Richmond, Virginia. Five enslaved people, among them Bob, Joe, and Linsey, escaped for "parts unknown," armed with $1,500 in cash taken from one of their slaveholders. Indeed, Bob, the enslaved man who fled from the slave trading firm of Jones & Slater had "enjoyed their fullest confidence," and was entrusted with making regular bank deposits for the slave traders.

On Tuesday, February 20, 1855, two enslaved people escaped from Richmond, Virginia, on the heels of another "stampede" of five freedom seekers the previous month. Their fate is unknown.

On Sunday evening, May 21, 1855, around eight enslaved Missourians escaped via boat from St. Louis, with the aid of Mary Meachum, a prominent free African American in the city. However, authorities were waiting on the opposite shore, and five of the escapees were recaptured. Meachum and two other free blacks were later charged with assisting the escapees to flee.

On Wednesday night, June 6, 1855, a group of enslaved people escaped from the Byrnes plantation in Bourbon county, Kentucky. When the slaveholder, Byrnes, attempted to stop the escape, a violent confrontation ensued, where the enslaver was "severely handled" and left unconscious on the ground. The number of freedom seekers, or their names, were not recorded, but they reportedly crossed the Ohio river "about ten miles below" Cincinnati.

On Saturday night, June 16, 1855, five enslaved people escaped from Norfolk, Virginia. Attempting to escape aboard a northern-bound ship, they were betrayed and turned over to local authorities. Then on Sunday morning, June 24, another group of 15 freedom seekers escaped by boat from Norfolk. Their fate is unknown, but later in September several freedom seekers from Norfolk appeared in Syracuse, New York. They may have been from this second group of runaways.

On Sunday, August 19, 1855, six freedom seekers, who were not named, escaped from Piedmont, Virginia. They fled from enslavers Isaac Parsons, G.W. Blue, G.W. Washington, William Donaldson, and Isaac Baker. Their fate remains unknown.

During the late summer and early autumn of 1855, there were numerous "stampedes" from Trimble county, Kentucky. A Madison, Indiana newspaper reported that there were "almost daily" escapes, and noted the escape of two freedom seekers held by Dr. William Ely of Milton, Kentucky.

In the span of about two weeks in early September, around 15 to 20 enslaved people escaped from Loudon county, Virginia, in what a local paper called a "wholesale stampede." The names of the freedom seekers were not recorded, but four individuals escaped from slaveholder John M. Harrison, three from a man named Skinner, three from a slaveholder named Stevenson, two from Joseph Lodge, and one from Cornelius Vandoventer, one from Joseph Meade, one from C. R. Dowell, one from Dr. F.

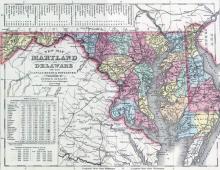

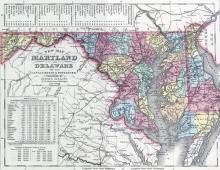

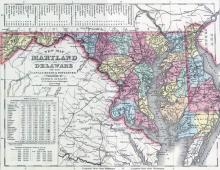

On Saturday night, September 15, 1855, a group of freedom seekers escaped from near Chestertown, Maryland, traveling via three horses and a carriage. Accounts vary about the size of the group, alternating between 10 and 21 people.The freedom seekers passed through Rochester, New York, where Frederick Douglass announced in his newspaper that he had "the pleasure of shaking seven of them by the hand," before the freedom seekers reportedly journeyed on to Canada.

Between Friday night, September 21 to Tuesday September 25, the Louisville Courier tallied seven enslaved people who had escaped from near Louisville, Kentucky. The ultimate fate of the seven freedom seekers remains unknown, but the "regular and constant stampede" clearly unnerved Louisville's slaveholding class.

Sometime in early October 1855, 11 enslaved people escaped from Ouachita county, Arkansas. A "general stampede among the negroes" was feared, and slaveholders feared "a concert of action" among local enslaved people. The fate of the 11 freedom seekers, however, remains unknown.

In October 1855, a correspondent to the Vicksburg, Mississippi Whig mentioned a "general stampede" of "some ten or fifteen" enslaved people from near Raymond, Mississippi. The enslaved people had apparently been hired out ("or rented") by slaveholders in Raymond, and the "stampede" may have been connected to a fever outbreak.

On Saturday night, October 27, 1855, seven enslaved people broke open a locked door and escaped from the slave pen of Jones & Slater in Richmond, Virginia. Three of the freedom seekers had been arrested previously, after attempting to escape from Bath county, Virginia. They were slated to be sold south.

Sometime in November 1855, a group of freedom seekers escaped from Union in Monroe county, Virginia. The number of runaways was not specified, nor were their names recorded, but reports did specify that the slaveholder, J.L. Hutchinson, lost $2,000 in human "property."

On Saturday night, November 3, 1855, six enslaved people, heavily armed, mounted horses near Fairmont, Virginia and galloped northwards towards freedom. One man was recaptured, but the remainder apparently eluded re-enslavement, despite their enslavers offering a $1,000 reward for their recapture.

Sometime in mid-November 1855, some 18 enslaved people--both men and women--escaped from Portsmouth and Norfolk, Virginia. Their fate remains unknown, but the escape did prompt concerned slaveholders to contemplate forming a squadron of slave patrolling vessels.

On Saturday night, November 24, 1855, six freedom seekers, who were not identified by name, escaped from Richmond, Virginia. Their destination is unknown, but Richmond journalists suspected that they had traveled along the "underground railroad, and are now, no doubt, on their way to the North."

On Saturday, December 1, 1855, some 11 enslaved people--seven men and four women--escaped from Richmond, Virginia. Their fate remains unknown.

Sometime in December 1855, some 40 enslaved people escaped in a "stampede" from Natchez, Mississippi. According to the Memphis, Tennessee Appeal, suspicions ran high that the freedom seekers "were carried off by some up-river boat, in the hands of Abolitionists of negro thieves." But the mode of escape, or ultimate fate of the freedom seekers remains unknown.

On Sunday night, December 16, 1855, seven enslaved people escaped in a "splendid carriage" from Millersburg in Bourbon county, Kentucky. But on attempting to cross the Ohio river near Maysville, their skiff leaked and filled with water, tragically drowning a woman and her three children. The survivors were re-enslaved.

On Christmas Eve 1855, six enslaved people--four men and two women--escaped from Middleburg in Loudon county, Virginia. Traveling on horseback and in a carriage, and heavily armed, the freedom seekers passed near Hood's Mill (near Eldersburg), Maryland the following day, where white residents sounded the alarm and started in pursuit. They shot and wounded one of the freedom seekers, and recaptured him, and later recaptured another of the men, who was named Joe.

In one of the most famous and tragic episodes of the fugitive slave crisis, a group of 16 freedom seekers escaped from Boone county, Kentucky on Sunday, January 27, 1856. After crossing the Ohio river, eight members of the Garner family were overtaken by a posse of slave catchers and federal officers. Forced to surrender, freedom seeking mother Margaret Garner killed her young child, rather than see the child be returned to the horrors of slavery.

Throughout late January and early February 1856, enslaved people launched a startling series of "stampedes" from Boone county, Kentucky and the surrounding counties. The Ohio river had frozen, temporarily forming an icy "bridge," and enslaved Kentuckians seized the moment for a mass exodus from bondage. Some estimates place the number of freedom seekers as high as 200 during this period.

On Friday night, February 1, 1856, six enslaved Kentuckians were "taken with a sudden leaving" and escaped into Ohio. They likely crossed the river by way of the "icy bridge" that frigid winter conditions had created, near California, Kentucky. Their ultimate fate remains unknown.

Sometime in mid-April 1856, 30 enslaved people escaped from Asheville, North Carolina, bound for "parts unknown." They were claimed by slaveholder Samuel S. Simmons. An Asheville journalist remarked on this "stampede," noting: "This is 'running away' by the wholesale."

On Friday night, May 16, 1856, eight freedom seekers--six men and two women--escaped from a Romney, Virginia jail. Heading northward, the freedom seekers were overtaken and re-enslaved on Sunday, May 18, after a "desperate fight," in which two of the runaways were badly wounded.

Around July 10, 1856, three enslaved people escaped from the residence of prominent St. Louis citizen John O'Fallon. Apparently never recaptured, their escape may have been linked to the flight of eight enslaved people from slaveholder Robert Wash just days later. On Monday night, July 14, 1856, an enslaved family--a husband and wife, their three sons, two daughters and the wife's sister, escaped from slaveholder Robert Wash near St. Louis.

On Sunday night, August 10, 1856, seven enslaved people escaped from Parkersburg, Virginia. Their ultimate fate remains unknown.

On Sunday, August 31, 1856, five enslaved people, whose names were not recorded, escaped from Jamestown, Kentucky into Ohio. Their fate remains unknown.

On Sunday night, August 31, 1856, a group of freedom seekers escaped from multiple slaveholders in Hopkins county, Kentucky. There were anywhere from 15 to 20 freedom seekers involved in the "stampede." One enslaved man from Tennessee was captured while attempting to join the group, but the fate of the others remains unknown.

Sometime in mid-September 1856, an enslaved railroad worker commandeered an engine near Sommerville, Tennessee. With "seven or eight other" enslaved people on board, they attempted to escape. Newspapers treated it with satire, labelling it a "novel negro stampede," but for the freedom seekers it meant the difference between a life of liberty or bondage. The group abandoned the engine some 12 miles outside of Sommerville, and fled to the woods.

On Sunday night, September 14, 1856, eleven enslaved people--eight adults and three children--escaped from Loudon county, Virginia. Their ultimate fate remains unknown.

Sometime in the fall of 1856, a "proposed negro stampede" was thwarted in Hallettsville, in Lavaca county, Texas. Several white men "of doubtful character" were alleged to have been involved in planning and aiding the escape plot. Placed on trial, a local jury returned a verdict of not guilty, but nonetheless required the men to leave the county in 48 hours. The number of enslaved Texans who attempted to escape was not specified.

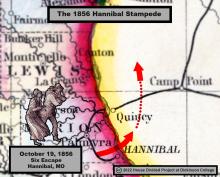

On Sunday night, October 19, 1856, a free African American preacher named Isaac McDaniel rescued from slavery his wife, Mary, their five-year-old son Daniel, and another family enslaved by Hannibal slaveholder John Bush: 32-year-old Anthony, his wife, 34-year-old Eliza, and their children, eight-year-old Margaret and six-year-old Lewis. Taking Bush's horse and carriage, McDaniel led the two families of freedom seekers out of slavery.

Sometime in early November 1856, two groups of freedom seekers, numbering 26 enslaved people, escaped from northern Kentucky. Fourteen freedom seekers left Kenton county, while another 12 escaped from near Maysville, Kentucky. Their ultimate fate remains unknown.

Reports described a stampede of free African Americans from Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Local whites had become angered by free Blacks' "pernicious influence among the slave population."

On Saturday night, January 10, 1857, eleven enslaved people escaped from a Richmond slave pen. Authorities expressed confidence they could recapture the freedom seekers, but their ultimate fate remains unknown.

In early February 1857, the frozen Ohio river provided a natural conduit to freedom for many enslaved Kentuckians. A family of six escaped from Covington, Kentucky during the first week of February, though a Cincinnati journalist noted that "numerous other stampedes have taken place along the line of the river."

On Saturday, April 11, 1857, five enslaved people escaped from the vicinity of Frederick, Maryland. Two freedom seekers fled from enslaver Abdiel Unkefer in Libertytown, Marlyand, and another three people escaped from slaveholding lawyer Dawson Hammond near the town of New Market. Their fate remains unknown.

On Saturday, May 30, 1857, five enslaved people escaped from Hagerstown, Maryland via horse, carriage, and buggy. They traveled to Chambersburg, where they apparently boarded the trains of the Cumberland Valley Railroad for Harrisburg. Although an initial report suggested the freedom seekers had been captured at Chambersburg, subsequent news items clarified that only the horses and carriages had been found.

Throughout May 1857, some 31 enslaved people escaped from the vicinity of Fort Adams, Mississippi. Their names, or mode of escape, were not recorded. It remains unclear if any of the freedom seekers were recaptured.

On Saturday, August 22, 1857, around 15 enslaved people in the nation's capital clambered into a wagon, having received permission from their enslavers to attend a religious camp meeting. Instead they seized the opportunity to escape, and headed for Pennsylvania. Nine were reportedly recaptured by a Baltimore slave catcher, but the fate of the remaining freedom seekers is unclear.

Late August 1857 saw a "general stampede" of enslaved people from Dover, Delaware. Although their names were not recorded, reports indicate that a number of enslaved people escaped from multiple slaveholders.

In early September 1857, some 12 enslaved people escaped from Norfolk, Virginia. Their names were not recorded, though multiple newspapers across the country reported on yet "another negro stampede."